Doris Kearns Goodwin, Guest Curator of the Newseum’s ‘Every Four Years: Presidential Campaign Coverage, 1896-2000,’ spoke during the exhibit’s opening on February 9. This show explores relationships among reporters and candidates in 20th century presidential campaigns. Excerpts follow.

Warren G. Harding smiling as he pretends to operate a newsreel camera. From “Every Four Years,” at the Newseum/NY. Photo courtesy Corbis Images.

I think there are two ways of looking at this exhibit. On the one hand, you can see the arc of change over the century from the days when McKinley sat on his front porch, in the days before the man sought the office, rather the office sought the man. So 750,000 people actually traveled to Canton, Ohio, from all over the country to see him sitting on his front porch and talking and reporters stood on the lawn with pads and pencils recording his remarks.

And you move from that moment to the present day where the candidates come to the cites and towns and even to the homes of the people through the television and the Internet and reporters following along, first on trains, then on jet planes. In some sense, with each advance in technology, reducing the intimacy of the relationship between the reporters and the candidates.

James Reston once said he felt nostalgia for the old whistle-stop train days when he started out as a reporter, when they would sit together drinking, smoking, talking late at night, exchanging anecdotes with the candidates. He said, “The higher we flew, the less we knew.”

And you can also see big changes over time in the relationships between the candidates and the reporters as the primaries replaced the party bosses to nominate the candidates. First newspapers, then radio, then television replaced the parties as the central screening mechanism to give the citizens information about the candidates. This put the media into a much more important role and escalated the age-old tension between the candidates and the members of the media.

On the other hand, what is so interesting [in this exhibit] is to see the continuing unchanging themes, such that even in the campaign of 2000 we can find echoes from this distant past…. There is the constant struggle for the candidates to project the image they want to project vs. the reporters wanting to project the image of the candidate that they see and want to describe. Witness that in 2000 we’ve talked about image over and over again, ranging from George W. Bush’s smirk to Al Gore’s continuing changing wardrobe to reflect his earth tones, to poor Steve Forbes’s awkward facial expressions.

That concern [about image] goes way back to Teddy Roosevelt, when he was sort of the official campaign advisor for William Howard Taft, who weighed 350 pounds. And he told Taft, “Don’t ever appear on a horse,” even though there is a picture of him on a horse here, “because it will be cruel to the horse and dangerous for you.” He also advised him, “Don’t ever play golf in public because golf is a dude’s game and the working men don’t like it.” But Taft was able to persuade the reporters who were his friends to let him play golf and not take pictures of it.

My favorite story of image from earlier days concerns Calvin Coolidge. He had a very sour personality, so sour that Alice Roosevelt Longworth said that he was weaned on a pickle. So they had to figure out a way to warm him up before the election. So they went to a PR guy, Ed Bernays, and they brought him to Washington and he figured out that he would bring down a troop of Broadway people including Al Jolson, the great singer, and hopefully they could get him to smile, which no one could. Then they’d take a picture and he would look warm and fuzzy.

So he brings Al Jolson and all the troops down and they go through the receiving line and not a single smile from Coolidge and he [Bernays] is panicking. They bring him out to the White House lawn and finally Jolson sings a song to Coolidge, “Keep Cool With Coolidge in the Good Old USA.” And there is a slight smile on Coolidge’s face. Cameras get it. Front page of The New York Times: “Coolidge Nearly Laughs.” Every reporter had the same thing. “Coolidge Smiles.” He wins the election three weeks later….

We can also see a continuing theme in these exhibits of the shifting boundaries of what defines what should be private and what should be public, what is appropriate for reporters to cover. Consider the fact that in 1936 there was an unwritten code of honor in Roosevelt’s era that reporters would not show him in a wheelchair or on crutches or with his braces on. A dramatic example occurred in 1936, when on his way to deliver his acceptance speech at the Democratic convention, he reached over to shake the hand of a supporter, lost his balance, his braces unlocked, he fell on the floor, his speech sprawled in front of him. He simply said to the Secret Service, “Clean me up.” He got up to the podium, somehow got his speech back together, and delivered the great “Rendezvous With Destiny” speech. Not a picture of him falling nor even a mention in the papers the next day that he had fallen. They simply reported the speech.

Contrast that with poor Bob Dole falling in 1996 off the stage in Chico, California…. He had leaned against a railing that hadn’t been securely tightened. It had nothing to do with his age that he fell. A 10-year-old, had he leaned on that, would have fallen. But Dole had just mentioned, unfortunately, the Brooklyn Dodgers, which were no longer of course the Brooklyn Dodgers. Reporters drew from that fall that he was too feeble to remember what decade he was in and too feeble to even stand on his feet, drawing an unfair metaphor from this unfortunate fall. Then, of course, in this campaign we’ve had the great pleasure of watching Gary Bauer shoot pancakes up in the air and fall backwards off the stage. It is almost as if there is a relish to find these embarrassing moments where that code of honor existed so many years before.

And then you can look in the current campaign, too, and the generally positive coverage that McCain has gotten and realize the impact of a candidate’s ability to reach out to the press and give the press what it needs—anecdotes, stories, openness, access. There are parallels with Teddy Roosevelt, who was really the first candidate who began to share anecdotes and colorful remarks. He invited the press to see his family, to tell stories about the family, and it was just at a time when photography was coming into the newspapers. The mass market papers loved human-interest stories. He understood that and played perfectly into their hands.

It spoiled every other candidate, however, because the press then thought they could get equal access to other candidates, so they actually followed his opponent, Alvin Parker, around on his morning ritual, a skinny-dip in the Hudson River. He was not too pleased about that.

But the interest in personality rose with the changing tide of photojournalism at that time. And then when Franklin Roosevelt came along, though publishers were routinely hostile to Roosevelt because of his New Deal, he was able to establish a relationship with the working reporters that cut across that line. There is an example at one time when he is on his train and one of the reporters missed getting on the train stop and couldn’t write his copy, so Roosevelt actually wrote the copy for the reporter so his editor wouldn’t be mad. And as a result, there was a full and fair coverage in the news part of the newspapers even if the publishers hated Franklin Roosevelt….

The interesting reporter story of the 1948 campaign is that there was a poll of 50 of the top political writers who were on the train with Truman. They were asked to predict who was going to win. To a person, they all predicted Dewey. Fifty to nothing. In the morning, the Newsweek poll came out. Clark Clifford, Truman’s advisor, was so excited that he went out of the train to get the poll. And he went and saw it and his face fell. So he hid it in his jacket as he came back into the train not wanting Truman to see it. But Truman knew immediately.

“What have you got there? I know you’ve got it there. Let me see it,” he said. Sheepishly he handed it to Truman. Truman looked at it. Didn’t bother him at all. “These guys wouldn’t have enough sense to pound sand into a rat hole,” he said. “Don’t worry about it. Let’s go on.”

And the interesting thing is that after that campaign, James Reston wrote an article in The New York Times apologizing for their not seeing with their own eyes and not writing what they had seen with their own eyes. They’d seen the enthusiasm of the crowds. They had seen the intensity of the relationship that Truman was developing. But, Reston said, “We listened to the tangibles instead of the intangibles. We listened to the polls. We fooled ourselves in a way.”

Interestingly, there was recently an interview with Joe Klein on television talking about the fact that in that last week in New Hampshire reporters didn’t know what to make of these polls that showed that George Bush was surging. They were writing about them. But David Broder, an old hand, looked at Joe Klein and said, “Don’t listen to the polls. Look with your eyes.” They saw the enthusiasm for McCain, and that was better than the polls at that point.

…As the new century dawns, the struggle between candidates and the media continues. Over the years, one could argue that the coverage of campaigns has become less partisan, more sophisticated, more capable of holding the candidates accountable. After the low point of 1988, featuring that Willie Horton ad, television and newspapers inaugurated ad watches. They have had a great impact on looking at the accuracy of ads, making citizens more cynical about the ads, even making ads, in my optimistic judgment, less important now than they were in the past….

The percentage of people who can vote who go to the polls has declined precipitously from eight in 10 in 1900 to only five in 10 today. So it seems to me that the challenge for both the candidates and the media in the years ahead is somehow how to come together to stimulate more interest and a deeper involvement on the part of the people. For in the end, the candidates and the reporters need each other desperately. The truth is, as one reporter said, “They use each other at every turn,” as it should be in a sometimes chaotic but always useful democracy.

President William McKinley speaks to supporters from the front porch of his Canton, Ohio, home during his re-election campaign in 1900. From “Every Four Years,” on display through November 12. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

In the question and answer session that followed, Goodwin elaborated on some of her earlier remarks.

In the old days reporters used to have code words for people. For people who were alcoholics, they said “they had a tendency toward excessive conviviality,” and if somebody was a womanizer, instead of mentioning it—they knew that Harding had girlfriends. They knew one of his Republican supporters had sent one of his mistresses to the Orient to get her out of the country but they didn’t think that was anybody’s business. Obviously, now since Gary Hart, it has become people’s business…. After we went through the impeachment scandal, there is less willingness on the part of the citizens to tolerate too much of this dragging out of public lives. And the press have had their own seminars, their own investigations into where is the proper line to be drawn, and I have a feeling we are turning back a little bit and there will be less of this. It will always be in the tabloids, but I suspect that in the major papers there is going to be more caution before they start revealing these things. At least, I hope so.

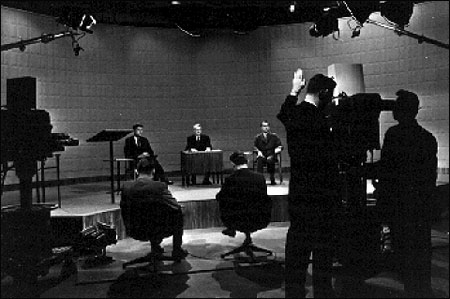

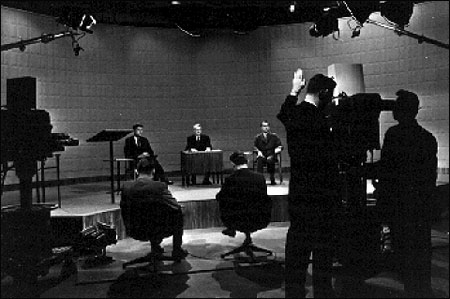

1960 debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, from “Every Four Years.” Photo courtesy Corbis Images.

Doris Kearns Goodwin won the 1995 Pulitzer Prize for History for her book, “No Ordinary Time—Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II.”

Warren G. Harding smiling as he pretends to operate a newsreel camera. From “Every Four Years,” at the Newseum/NY. Photo courtesy Corbis Images.

I think there are two ways of looking at this exhibit. On the one hand, you can see the arc of change over the century from the days when McKinley sat on his front porch, in the days before the man sought the office, rather the office sought the man. So 750,000 people actually traveled to Canton, Ohio, from all over the country to see him sitting on his front porch and talking and reporters stood on the lawn with pads and pencils recording his remarks.

And you move from that moment to the present day where the candidates come to the cites and towns and even to the homes of the people through the television and the Internet and reporters following along, first on trains, then on jet planes. In some sense, with each advance in technology, reducing the intimacy of the relationship between the reporters and the candidates.

James Reston once said he felt nostalgia for the old whistle-stop train days when he started out as a reporter, when they would sit together drinking, smoking, talking late at night, exchanging anecdotes with the candidates. He said, “The higher we flew, the less we knew.”

And you can also see big changes over time in the relationships between the candidates and the reporters as the primaries replaced the party bosses to nominate the candidates. First newspapers, then radio, then television replaced the parties as the central screening mechanism to give the citizens information about the candidates. This put the media into a much more important role and escalated the age-old tension between the candidates and the members of the media.

On the other hand, what is so interesting [in this exhibit] is to see the continuing unchanging themes, such that even in the campaign of 2000 we can find echoes from this distant past…. There is the constant struggle for the candidates to project the image they want to project vs. the reporters wanting to project the image of the candidate that they see and want to describe. Witness that in 2000 we’ve talked about image over and over again, ranging from George W. Bush’s smirk to Al Gore’s continuing changing wardrobe to reflect his earth tones, to poor Steve Forbes’s awkward facial expressions.

That concern [about image] goes way back to Teddy Roosevelt, when he was sort of the official campaign advisor for William Howard Taft, who weighed 350 pounds. And he told Taft, “Don’t ever appear on a horse,” even though there is a picture of him on a horse here, “because it will be cruel to the horse and dangerous for you.” He also advised him, “Don’t ever play golf in public because golf is a dude’s game and the working men don’t like it.” But Taft was able to persuade the reporters who were his friends to let him play golf and not take pictures of it.

My favorite story of image from earlier days concerns Calvin Coolidge. He had a very sour personality, so sour that Alice Roosevelt Longworth said that he was weaned on a pickle. So they had to figure out a way to warm him up before the election. So they went to a PR guy, Ed Bernays, and they brought him to Washington and he figured out that he would bring down a troop of Broadway people including Al Jolson, the great singer, and hopefully they could get him to smile, which no one could. Then they’d take a picture and he would look warm and fuzzy.

So he brings Al Jolson and all the troops down and they go through the receiving line and not a single smile from Coolidge and he [Bernays] is panicking. They bring him out to the White House lawn and finally Jolson sings a song to Coolidge, “Keep Cool With Coolidge in the Good Old USA.” And there is a slight smile on Coolidge’s face. Cameras get it. Front page of The New York Times: “Coolidge Nearly Laughs.” Every reporter had the same thing. “Coolidge Smiles.” He wins the election three weeks later….

We can also see a continuing theme in these exhibits of the shifting boundaries of what defines what should be private and what should be public, what is appropriate for reporters to cover. Consider the fact that in 1936 there was an unwritten code of honor in Roosevelt’s era that reporters would not show him in a wheelchair or on crutches or with his braces on. A dramatic example occurred in 1936, when on his way to deliver his acceptance speech at the Democratic convention, he reached over to shake the hand of a supporter, lost his balance, his braces unlocked, he fell on the floor, his speech sprawled in front of him. He simply said to the Secret Service, “Clean me up.” He got up to the podium, somehow got his speech back together, and delivered the great “Rendezvous With Destiny” speech. Not a picture of him falling nor even a mention in the papers the next day that he had fallen. They simply reported the speech.

Contrast that with poor Bob Dole falling in 1996 off the stage in Chico, California…. He had leaned against a railing that hadn’t been securely tightened. It had nothing to do with his age that he fell. A 10-year-old, had he leaned on that, would have fallen. But Dole had just mentioned, unfortunately, the Brooklyn Dodgers, which were no longer of course the Brooklyn Dodgers. Reporters drew from that fall that he was too feeble to remember what decade he was in and too feeble to even stand on his feet, drawing an unfair metaphor from this unfortunate fall. Then, of course, in this campaign we’ve had the great pleasure of watching Gary Bauer shoot pancakes up in the air and fall backwards off the stage. It is almost as if there is a relish to find these embarrassing moments where that code of honor existed so many years before.

And then you can look in the current campaign, too, and the generally positive coverage that McCain has gotten and realize the impact of a candidate’s ability to reach out to the press and give the press what it needs—anecdotes, stories, openness, access. There are parallels with Teddy Roosevelt, who was really the first candidate who began to share anecdotes and colorful remarks. He invited the press to see his family, to tell stories about the family, and it was just at a time when photography was coming into the newspapers. The mass market papers loved human-interest stories. He understood that and played perfectly into their hands.

It spoiled every other candidate, however, because the press then thought they could get equal access to other candidates, so they actually followed his opponent, Alvin Parker, around on his morning ritual, a skinny-dip in the Hudson River. He was not too pleased about that.

But the interest in personality rose with the changing tide of photojournalism at that time. And then when Franklin Roosevelt came along, though publishers were routinely hostile to Roosevelt because of his New Deal, he was able to establish a relationship with the working reporters that cut across that line. There is an example at one time when he is on his train and one of the reporters missed getting on the train stop and couldn’t write his copy, so Roosevelt actually wrote the copy for the reporter so his editor wouldn’t be mad. And as a result, there was a full and fair coverage in the news part of the newspapers even if the publishers hated Franklin Roosevelt….

The interesting reporter story of the 1948 campaign is that there was a poll of 50 of the top political writers who were on the train with Truman. They were asked to predict who was going to win. To a person, they all predicted Dewey. Fifty to nothing. In the morning, the Newsweek poll came out. Clark Clifford, Truman’s advisor, was so excited that he went out of the train to get the poll. And he went and saw it and his face fell. So he hid it in his jacket as he came back into the train not wanting Truman to see it. But Truman knew immediately.

“What have you got there? I know you’ve got it there. Let me see it,” he said. Sheepishly he handed it to Truman. Truman looked at it. Didn’t bother him at all. “These guys wouldn’t have enough sense to pound sand into a rat hole,” he said. “Don’t worry about it. Let’s go on.”

And the interesting thing is that after that campaign, James Reston wrote an article in The New York Times apologizing for their not seeing with their own eyes and not writing what they had seen with their own eyes. They’d seen the enthusiasm of the crowds. They had seen the intensity of the relationship that Truman was developing. But, Reston said, “We listened to the tangibles instead of the intangibles. We listened to the polls. We fooled ourselves in a way.”

Interestingly, there was recently an interview with Joe Klein on television talking about the fact that in that last week in New Hampshire reporters didn’t know what to make of these polls that showed that George Bush was surging. They were writing about them. But David Broder, an old hand, looked at Joe Klein and said, “Don’t listen to the polls. Look with your eyes.” They saw the enthusiasm for McCain, and that was better than the polls at that point.

…As the new century dawns, the struggle between candidates and the media continues. Over the years, one could argue that the coverage of campaigns has become less partisan, more sophisticated, more capable of holding the candidates accountable. After the low point of 1988, featuring that Willie Horton ad, television and newspapers inaugurated ad watches. They have had a great impact on looking at the accuracy of ads, making citizens more cynical about the ads, even making ads, in my optimistic judgment, less important now than they were in the past….

The percentage of people who can vote who go to the polls has declined precipitously from eight in 10 in 1900 to only five in 10 today. So it seems to me that the challenge for both the candidates and the media in the years ahead is somehow how to come together to stimulate more interest and a deeper involvement on the part of the people. For in the end, the candidates and the reporters need each other desperately. The truth is, as one reporter said, “They use each other at every turn,” as it should be in a sometimes chaotic but always useful democracy.

President William McKinley speaks to supporters from the front porch of his Canton, Ohio, home during his re-election campaign in 1900. From “Every Four Years,” on display through November 12. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

In the question and answer session that followed, Goodwin elaborated on some of her earlier remarks.

In the old days reporters used to have code words for people. For people who were alcoholics, they said “they had a tendency toward excessive conviviality,” and if somebody was a womanizer, instead of mentioning it—they knew that Harding had girlfriends. They knew one of his Republican supporters had sent one of his mistresses to the Orient to get her out of the country but they didn’t think that was anybody’s business. Obviously, now since Gary Hart, it has become people’s business…. After we went through the impeachment scandal, there is less willingness on the part of the citizens to tolerate too much of this dragging out of public lives. And the press have had their own seminars, their own investigations into where is the proper line to be drawn, and I have a feeling we are turning back a little bit and there will be less of this. It will always be in the tabloids, but I suspect that in the major papers there is going to be more caution before they start revealing these things. At least, I hope so.

1960 debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, from “Every Four Years.” Photo courtesy Corbis Images.

Doris Kearns Goodwin won the 1995 Pulitzer Prize for History for her book, “No Ordinary Time—Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II.”