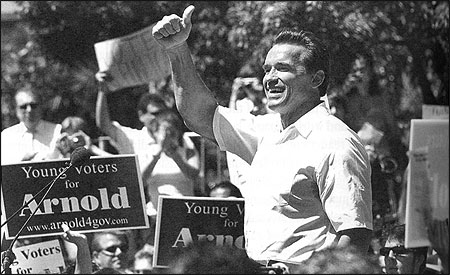

In early August, Arnold Schwarzenegger went to the offices of the Los Angeles County registrar of voters to file as a candidate for governor in California’s recall election. He held a news conference the same day—what would prove to be one of only two free-for-all press events. A colleague covering the appearance for a San Francisco TV station counted more than 30 television cameras at the event.

After several minutes, a press aide announced, “One more question.” Schwarzenegger, showing an understanding of his own campaign strategy that would dominate the recall campaign, called on a reporter from “Entertainment Tonight” (ET). The hardhitting question: When will actor Rob Lowe be making an appearance on Schwarzenegger’s behalf?

And so the news conference came to an end without any meaningful details from Schwarzenegger about how he would balance the state’s deficit-ridden budget, protect spending on public schools, and reduce taxes. Instead, he managed to repeat what would be the only message of his campaign—he would be an upbeat agent of change from the state’s do-nothing political status quo.

There’s nothing new about candidates or officeholders calling on reporters who are likely to ask softball questions. There’s nothing new about a candidate, or a President, holding a minimal number of news conferences. And there’s certainly nothing new about a candidate figuring out a campaign strategy that essentially bypasses the political news media. What was unusual was to see a candidate who so completely understood the nature of modern political reporting and was so uniquely positioned to take advantage of a new era in campaign information.

Arnold Schwarzenegger campaigns at California State University in Long Beach. Photo by Aurelia Ventura/La Opinión.

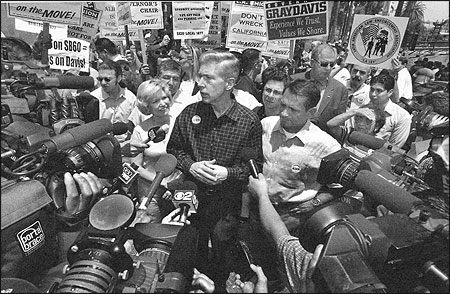

The press spotlights Governor Gray Davis during a rally to defeat the recall. Photo by Ciro Cesar/La Opinión.

Changes in Political Reporting

What was remarkable about the recall campaign had less to do with Schwarzenegger’s barnstorming candidacy and more to do with how the political press corps has changed in a very short time from a small group of veteran reporters with an abiding interest in campaigns and issues to a massive multimedia experience in which huge and small information sources overlap and interconnect and spend as much time attending to each other as they do to the job of reporting on a campaign.

What this campaign illuminated for me were the sweeping changes in political reporting that have happened during the past decade or so. For more than 25 years, I have been involved in state and national political reporting at newspapers. During the past 13 years, I took a break from political reporting to write a general interest column, first at a local newspaper in Palo Alto, then for the last 10 years at the San Francisco Chronicle. Then this spring, wearying of the sound of my own voice, I surrendered the column and began to cover politics for the paper, unaware that a historic recall election was in the offing.

What I found is that much had changed about how the political press corps perceives and pursues its job due to the increased importance of TV and radio talk shows and the rising impact of the Internet as a means of conveying information and as a vehicle for the public to observe and comment on political reporting. And while there had always been a notable self-awareness among political reporters—when we could, we often read each other’s work to see who was ahead and whom we had to follow—the Internet and the airwaves have lifted that to an astonishing level of self-absorption.

It’s that self-absorption that represents the biggest concern about the new era of political reporting—an era in which the reporter has become more important than readers or voters.

Certainly, there was no Internet 13 years ago. Then, as colleague Robert B. Gunnison noted in a piece for the California Journal, a California-based monthly about politics and government, the press corps consisted of re-porters—usually garbed in blue blazers and khaki trousers—from a dozen or so newspapers around the state. The occasional TV station had a reporter assigned to politics, but those were few and far between, and much of the campaign agenda was set by a small, collegial group of middle-aged, white males.

Clearly, the explosion of information outlets blew apart that old boys’ club and diversified the perspectives brought to politics, perhaps at the cost of expertise and institutional knowledge about both politics and government.

While the press corps might have lacked many things, it also was absent “Entertainment Tonight.” Obviously, without Schwarzenegger’s melding of celebrity and politics, “ET” might not have been on the campaign trail this time, either, but who’s to say there won’t be future coverage of politics in a manner historically reserved for show business? And if there was no “ET,” there also was no Romenesko, The Poynter Institute Web site that focuses solely on journalists and reinforces a hierarchy of media celebrities and big-time news outlets.

The National Journal’s Hotline, which enhanced the sense in California that the recall was a national story and dropped our names in front of our national peers, was a fledgling phenomenon 13 years ago. Thirteen years ago, there was no Rough & Tumble, a Web site (www.rtumble.com) that, like The Hotline, summarizes in a 24-hour cycle the leading stories on California politics and government. There were no Weblogs, in which reporters can describe their first impressions, circulate rumors, and race to be first—a real-time blog can always be corrected later—without the customary filter of editors or time or further reporting.

And in just the last few years, there has been an explosion of information distribution points among political junkies—dozens of individuals or organizations that post all or part of political news stories or circulate through e-mail their own lists of the top stories of the day, often reflecting the political perspective of the distributor’s special interests.

It has become a matter of daily routine to check a variety of Web sites to see where the newspaper’s reporting landed on the list of top stories. The more stories near the top, the more convinced we are that we dominated that day’s reporting. We could see if we were first with a story—a scoop—and we could be sure that our competitors around the state knew we were first and that we had a chance to show off our work to news outlets around the nation and enhance our own national reputation. This cycle fed on itself: We all wanted to write stories that would top the list.

At the same time, the recall election brought to California the circus of national radio talk shows and cable TV shout-fests. Earlier this year—before the recall election emerged but long after the development of the new multimedia era—the Chronicle established a new partnership with a Bay Area TV station and a small studio was installed in the newsroom, pushing aside a number of copyeditors. Routinely, in a break between deadlines, political reporters and columnists would sit down on the studio stool and make a quick TV appearance on one of the many cable shows that must keep feeding the voracious appetite of a 24-hour news hole.

Often the participant would walk away from the studio muttering that the main requirement for such an appearance is an ability to shout over the other guests. The cross-media partnership is not unique to the Chronicle, and it could be argued that every newspaper needs a strategy of integrated media. That’s a story for another time. But having this TV outlet for our reporting fed the growing sense that the coverage of the campaign was more about what we were doing—our ability to show off our expertise—than it was finding out what was on the minds of the voters and providing meaningful, useful information with which they could make an informed decision.

There always has been the tendency to cover the process, not the policies. But now, increasingly, the process seems to be all that is covered because it’s the best way to make a good impression among ourselves. After the election, Romenesko carried a report of some comments by a California newspaper editor who asserted that the state’s news corps did a poor job of covering the recall election. Too little attention was paid to what the voters were thinking. That editor was right—that newspaper fixated on Schwarzenegger’s immigrant status when he first arrived in the country.

It was classic “gotcha” journalism, an attempt to expose Schwarzenegger’s own positions on immigration as somehow hypocritical. It was never clear why the readers of that newspaper would find that information valuable. But assuming one role of the media is to tell people things they might want to know, that doesn’t explain the newspaper’s focus on the story over several days. That can only be explained as an attempt to attract attention, not from readers, but from other news outlets.

That kind of reporting should be distinguished from the Los Angeles Times’s stories in which women alleged that they were sexually harassed and abused and battered by Schwarzenegger. Those stories, thoroughly and credibly reported, touched on an issue that gave the public meaningful and timely insight into a candidate. The result was a bombardment of e-mails and Internet posts concerning the Times’s story, comments and reaction that indicated the story touched a nerve among readers, for better or for worse.

And that may be the last, significant irony in the changing nature of political reporting. The public now has more ways to reach the media, and we seem to listen less to them and more to each other. The public also has more ways to comment, more means by which to complain about bias or to offer up independent analysis, or participate in special-interest pressure tactics. The reverse also is true—we can reach more people now, ask for a broader range of opinion, and write stories that truly reflect the mood and attitude of the people who are participating in the political decision making.

In short, we have a better opportunity to do the two things good news reporting should do—tell the public something they didn’t know and put into words for them those things they can’t express for themselves.

The recall was a unique opportunity to reflect to readers what they were thinking, since it was an election that was less about what people knew and more about how they felt. The best reporting in the recall election captured what was on people’s minds, was an early forecast of a public hunger for change, an anger at a mismanaged status quo that had badly tarnished the Golden State.

But more commonly, reporting seemed to be driven by a desire to reflect ourselves to ourselves. A decade ago, no one thought a political reporter was a celebrity. Now it seems as though each of us wants to be one, not just cover one running for governor.

Mark Simon is a political reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle. He has covered California, Bay Area, and national politics for more than 25 years.