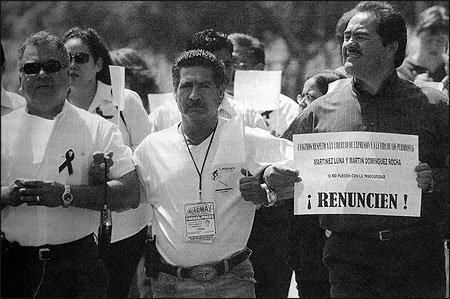

Mexican journalists march to the state attorney general's office to demand justice for the assassination in June 2004 of Francisco Ortiz, a Tijuana newspaper editor, in Tijuana, Mexico. The sign reads "Resign!" Photo by David Maung/Courtesy of The Associated Press.

Jose Luis Ortega Mata was a brave publisher of Semanario, a weekly newsmagazine in the Mexico-U.S. border town of Ojinaga, Chihuahua. He denounced drug trafficking in that northern region of Mexico and the relationship between drug lords with local police, politicians and businessmen. Early in 2001, he was about to publish a new report on how drug money was being used to finance political campaigns when a gunman shot him twice in the head, killing him on his way to his office.

He was murdered in February, and his death marked the opening of a violent five-year killing season against journalists in Mexico. Since then, at least 15 journalists have been killed or "disappeared" allegedly by drug kingpins, giving birth to a new phenomenon in the Mexican press: self-censorship because of fear.

Drug-lord mercenaries have expanded their original realm of violence from the border towns in the southern United States to places such as Veracruz on Mexico's Gulf Coast and Acapulco on its Pacific Coast. Drug trafficking has expanded from only five regions, where it was concentrated 15 years ago, to the whole country; there are now 32 states where organized crime is fully operational. This has created waves of fear that are felt even in Mexico City, which previously was immune to such dangers.

No journalist in Mexico who dares to write about drug trafficking should feel safe today. Since the federal government has been unable to stop the carnage, journalists who pursue this story have become the drug lords' enemy.

- In 2004, Javier Ortiz Franco, coeditor of a leading investigative newsmagazine, Zeta of Tijuana, was in charge of a special task force appointed by the Mexican government and the Inter American Press Association to investigate the 1998 murder of Zeta's cofounder, Felix Miranda, and the 1991 killing of its columnist, Victor Manuel Oropeza, from Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua. That happened when he arrived home with his two kids; he was murdered in front of them.

- In February of this year, a few days after El Mañana newspaper cohosted a seminar in its hometown of Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas about how to confront drug-related violence against journalists, gunmen stormed its headquarters. They fired assault rifles and tossed a grenade, injuring reporter Jaime Orozco Tey, who was shot five times. The day of the assault was a holiday, which explained why there was only one death, of a copy boy, and no other victims aside from Orozco.

The message of this newsroom assault was obvious: stop messing with drug-trafficking affairs. Its recipient was not necessarily meant to be El Mañana, but the Mexican press, as a whole.

Newspaper columnist Francisco Arratia Saldierna was beaten to death in August 2004 and his body left outside the offices of the Red Cross in the border city of Matamoros. Saldierna's column appeared in several papers throughout the border state of Tamaulipas. Photo courtesy of The Associated Press.

News Reporting Is Silenced

El Mañana was one newspaper that didn't need a fresh delivery of this message. Since 2004, when its editor, Roberto Javier Mora, was stabbed to death, the newspaper had begun to censor its coverage on drug trafficking and organized crime. Every drug-related story was published without any identifying details or further investigation. Nuevo Laredo is one of the two hottest places in Mexico where drug lords are fighting for control of the city. The main drug cartels, the Gulf and the Pacific, are trying to gain full control of that border town that is home to the main commercial border point of entry to the United States and the access to Interstate 95, which runs into the most lucrative emerging cocaine market in the United States. Dead bodies are found almost every day in Nuevo Laredo from one side or another, and their names, background or liaisons are never published by El Mañana. The newspaper publishes only the body count on the city streets.

As with El Mañana, newspapers and magazines in many cities in Mexico have stopped giving details of the ongoing urban battle for markets and cities. In places like Tijuana and Hermosillo, Sonora, reporters stopped going to cover stories at night or very early in the morning because they fear it might be a set up. They have in mind the case of young reporter Alfredo Jimenez, from El Imparcial in Hermosillo, who disappeared in April 2005 on his way to meet a federal police source. Jimenez was a notorious investigative reporter who had several scoops on the whereabouts of a number of members of one drug cartel in the region. Federal authorities investigating the crime didn't know that Jimenez was fed information from a rival cartel to damage its enemy and, when the "enemy" found out the original source of information; they are presumed to have murdered him.

It is now presumed that drug cartels feed information to reporters to blast their enemies. A number of Mexico City reporters recently went into a panic after El Universal newspaper broadcast on its Web page the full video of the execution of one gunman of Los Zetas, the Gulf Cartel hit squad. They realized they might have been used months before by the mercenaries that taped that video when they printed a description of the execution. When pushed by the federal authorities after the video broadcast to reveal who told them of the content of the tape before the Mexican government knew about it, the reporters decided to no longer pursue the story. A number of reporters who cover the federal police beat followed their colleagues' lead in solidarity.

Los Zetas is now synonymous with bloody violence, and a growing number of news outlets, most of them in northern Mexico, have stopped naming this cartel hit squad in their stories out of fear for their own safety. (Lawyers and media consultants pressure editors and reporters not to do it, as well.) Even more dramatic, the highly respected syndicated column of reporter Jesus Blancornelas, the cofounder and former editor of Zeta who survived a murder attempt by the former all-powerful Tijuana Cartel, was cancelled by a number of newspapers in Mexico because of the sensitive issues he covers.

A few years back self-censorship happened for financial reasons as newspapers and magazines stopped fighting hard against government repression of the press. Although there were cases in which government officials put pressure on publishers and editors to fire journalists they felt were "uncontrollable," there were only sporadic cases of physical violence against reporters and editors. These are new times. Now the drug wars provide new reasons for self-censorship to exist. In 2004 and 2005, among Latin American nations, Mexico had the highest number of journalists killed, more than long war-torn Colombia and the highly unstable Haiti. This recognition is nothing to be proud of, and there are many reasons for journalists to still be afraid.

This year some Mexican news organizations decided to confront this challenge by working together. Their model is based on the U.S. experience of the Arizona Project, created by independent journalists to continue the work of investigative reporter Don Bolles, who was assassinated while researching mob activities in Arizona. The Mexican newspapers agreed to investigate collectively the whereabouts of El Imparcial reporter Jimenez and publish every step in their investigation on the same day, without a byline, to protect the reporters involved in the project. This is a unique experience for Mexican newspapers, whose relationship is usually characterized by envy and distrust. But now there is no other choice; they must come together to face the drug kingpins at whatever cost might result and regardless of what the government does. This is especially the case since so far the government is losing the war against the drug cartels.

Raymundo Riva-Palacio, a 1992 Nieman Fellow, is managing editor of El Universal, a newspaper in Mexico City.