Filling a Notebook With Narrative

- Select a good topic.

- Secure good access.

- Find good narrative runs.

- Find character hints in action.

- Find the right scene details.

- Find emotionality for your subjects, not for you.

- Do some contextual research.

- Find or crystallize the point, the destination.

- Do a refined comparison of the difference between your views and your subject’s views.

- Cherish the structural ideas and metaphors that you have in the field.

- Create translated writer’s notes.

- Make a flow notation of scenes.

- Clean your prose.

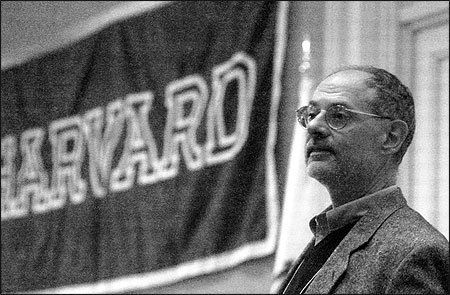

Mark Kramer

What you’re doing when you write narrative is creating a sequential intellectual/emotional experience for the reader. You may be doing coverage. You may be creating a record. You may be imparting information. You may be doing what my high school teachers called “showing your work,” as in, “Solve this problem. Show your work.” You may be sourcing. You may be doing all of the civically responsible things that reporters do. But the fact remains your readers will be having, whether you like it or not, a sequential intellectual/emotional experience when they read your work.

Once you write narrative, a dilemma comes right away, which is that you run into a war in the test between topicality and chronology. Somebody going through an experience will be crossing the topical categories of any outline of the subject, one after another. And when you do narrative, you want to have people acting through time. That’s the very definition of narrative. But when you’re presenting an orderly account of something, you want to cover it topic by topic by topic. The structure that we’re all so accustomed to reading, that is invisible to us, is the digression that we see actors acting—we wait while our friend the narrator explains stuff we need. Then we go back to action. It’s as simple as that.

My talk today is about how to come back with a notebook full of material that’s good for constructing a narrative piece. The implication is that there is a different style of reporting necessary than you would use in your daily business.

Select a good topic. How much you can do with a story depends very much on the strategy of how you conceive it. First of all, I want to discriminate between high emotional and low emotional valence stories. A high emotional valence story is a story to which readers bring a lot of emotionality. The most common high emotional valence story in the news is endangered babies.

It takes almost no work to energize reader’s concern for that sequential emotional experience. Once you have the reader engaged and concerned, you have them in the palm of your hand. You can digress; you can do whatever you want to do. They will forgive you anything. Endangered chil-dren—because they concern us, as a species—take no characterization, no contextualization.

There are some fools in the field who have tried to write narrative books about low emotional valence topics. Can you imagine a book about Russian agriculture? It’s really a good book. To make it a good book, a writer trying to do that kind of work has to marshal other tools than the species concerned with endangered babies.

Pace is the ultimate mystery for the writer. I define pace as the reader’s sense of urgency to continue to head somewhere. The cleaner your sentences, the less rattling around inside of a sentence to find out what refers to what, the easier the problem of keeping the reader’s sense of urgency intact. The more active your verbs, the more muscular, the more delightful your perceptions, the more lovely your metaphors, the easier the sense of pace. Whatever goes into good writing, think of it as a tributary in the river of pace, and that’s what you’re after.

When you do these low emotional valence subjects, you have to write in a more accomplished and self-aware way. These are the interesting topics for developing the promise of excellent narrative in media. The slowest topic is the flow of rocks, and John McPhee wrote four books about it.

If you’re looking for his secrets of pace, then in the margin of “Basin and Range,” his book about geology, keep a running tab of the answer to this: “What question am I wishing for the answer to right now?” And you will find that request changes almost by the paragraph, almost by the page, certainly by the chapter. They are tiny operant questions, and they are cunningly inserted to go along with the clean sense, the sharp-image characterizations of people, and anecdotal treatment of the material.

Secure good access. The Kramer “Rule of Travel” is if you want to go to Paris, Brussels or Toledo, Ohio, and you don’t know anybody in Paris, and you don’t know anybody in Brussels, and you have fascinating friends in Toledo, go to Toledo. Access is all. Your best idea is a lousy idea if you can’t see people living their lives, and I’m going to use a Henry James phrase, a “felt life” level. And I will define “felt life” as the level of informal comprehension that you show about the world at the end of your reporting day when you’re sitting at the edge of your bed, and you’re dog tired, and your significant other says, “What did you do today?” And you start saying “That road commissioner was a real asshole. He’s so pompous and vulgar and vain. He wears tacky clothing. Yet there is something sweet about him,” and so on.

For narrative, you want “felt life” level access. But felt life level access is extremely difficult to come by. It’s certainly possible to get good access, uncontaminated, intimate access. And when you do, it will raise a basic ethical question, the basic ethical question that Janet Malcolm deals with eloquently in “The Journalist and the Murderer”: You are being a professional, gathering in material that violates people’s sense of privacy sometimes in some ways. So the norms of friendship govern your source’s actions towards you and the norms of professional activity govern yours. And there is a moral crisis that you will have to resolve.

My blunt and frank contention is that we live on the slippery slope, we do not live on the edge of it, and prissily stay off it. We live there. You may not think so. And where one lives on the slope is almost a matter of personality, of personal choice. There are no two ways about it. Don’t do stories you don’t feel comfortable doing is the best advice I can give you.

Good access takes charm and guts and aplomb, and you will be taken at the level of sophistication that you bring to the subject. If you’re completely naive and gawky, you will be treated to the PR version of the subject. The more you know, the more you’ll be treated collegially. This will inspire more guarded but also more frank discussion. So you want to do a fair amount of homework beforehand, and you want to place yourself situationally in a way that can serve your reporting purposes.

Find good narrative runs. Ask your subject what’s his or her schedule for the next week, or two, or three. Find something interesting. Think to yourself, “What is this story about beyond the nominal subject?” The topic or location is not the subject of a piece. The subject of the piece you can’t possibly know until you get onto the site and see things starting to happen.

The obvious nominal narrative of a piece starts at the beginning and goes to the end. You need to know the chronology, the nominal chronology of what went on. You’re looking for some event that could be unfolded as a foreground narrative. So you’re looking for a narrative run, like this concept of a two-tiered narrative that there is the start-to-finish chronology and that you can pull a shorter run—because you’re in charge. You can say to the reader that you can start on the last day of your reporting.

The order in which you gather your material is very good for the tale of how an ignorant person became slightly less ignorant, but that’s not going to be your narrative. Your narrative is going to concern activities in the life of your subject. You may not falsify the sequence of what happened.

Find character hints in action. The more world sense you can bring to your general reporting, the more awareness you have of how life works, and the more you feel free to record that in your text, the better people will be served by what you write.

Find the right scene details. Do sensory reporting—this is important. Sight, sound, smell, touch and taste will, if you record details of these things, allow you to set strong scenes. The biggest basic mistake that beginning narrative writers, and even fairly accomplished writers, make is setting scenes too casually. You have to set a scene so the reader gets a feeling of volume, space, dimension and has sensory experience there. You don’t need to report on measurements and details in the detail that would be required if you were writing for Scene Diorama magazine. Nobody is interested in building a diorama of the scenes, but everybody wants to know what it feels like to be there.

The function of setting a scene is to foster the reader’s sense of immediacy. It’s not hard to do. It’s not complicated. Everybody here can do it first time out. All they have to do is consent to doing it in their own minds. And you can do it. If you can show persons in action, so much the better, because then you get to use stronger verbs.

Find emotionality for your subjects, not for you. When I first watched surgery, I said “Yuck, blood. Oh, this is scary. This is brutal.” But none of the actors on the stage were saying “Yuck, blood, this is scary, this is tough.” They were all socialized to that. My job was to record my own emotions because they would duplicate the reader’s emotions, and I had to know the emotional valence that I was writing into. But it’s much more interesting to notice that the surgeon was getting angry in his discussion about a political situation—who got which operating room and which set of workers for a certain procedure. Who was deferred to in the robing? Little things like that turned out to be important.

There is what I call a doctrine of strong-voiced writing. You are the host. You should have a pretty good idea of why you’re showing a scene and some cunning about how you do it. You are allowed to do that. Your editors will love it if you do that. They don’t know when you don’t do that because they aren’t accustomed to it. They probably won’t even know when you do do it. But it will feel like a good story.

Do some contextual research in the beginning in order to not get the PR snow job. I always talk about trying to island-hop an archipelago of knowledge across a broad Pacific of ignorance. That’s what you’re doing when you’re doing your background research. The reason you’re doing your background research is because narrative exists inside of a social context and an economic context, inside of many shells of context. The structural feature of running narrative, of stopping, digressing to the necessary background information, moving back to the story, is a very powerful structural technique.

You’re interested very deliberately in having digressive material to frame the story. That’s where you can do a lot of good in sorting complex topics narratively. My first tip and comment is that it’s frequently best to digress in the middle of the action, not between actions, because then we remember well and we’re happier to come back. The higher the emotional valence, the longer the digression, I’d say.

Find or crystallize the point, the destination. Destination is my term for what my high school English teacher used to call “the theme.” Destination is a reader’s eye view of themes.

If we go back to our initial contention that what you’re after is creating the right sequential intellectual/semotional experience for readers, then the readers should have very quickly installed (A) an emotional attitude towards the characters and towards the events, and (B) the sense that we’re being told this for a worthy reason. We’re being taken here and there and explained background and shown things because we’re heading towards a destination that we will be delighted to learn about. We don’t have to know the names of the important events, but we have to know that we’re going somewhere good in the hands of a good friend, our narrator. At the end, there has to be that pay off. The readers have to feel that they’ve arrived somewhere.

I want you to notice how late in the process it is and you still don’t know quite where you’re heading. You’re still interacting with your text, which bears 10,000 decisions that you’ve made.

Do a refined comparison of the difference between your views and your subject’s views, just so you can know how to navigate. I’m not saying to put your views aside, but you need to follow the rules of balance for whatever publication you’re doing it for. You also want to pay very careful attention to not being taken in by sophisticated public relations and congratulations on your understanding of the subject. You have to know what you don’t know as well as how you feel about what you do know.

Cherish the structural ideas and metaphors that you have in the field. You’ll suddenly say “Oh boy, I love this quote because it could be used to introduce this part of the topic or that part of the topic.” Or “Boy, this is a great visual. I can’t wait to be able to use this scene. It’s a great bridge between this and this.” You think that these are realizations that will stick to you like a piece of notepaper to a bulletin board. Your mind is not a bulletin board. The same goes for figures of speech, metaphors. They occur to you and you think “I can’t wait to use that in the text.” Nail them at the moment. Write notes to yourself on how to write. Record those metaphors on your note paper or in your computer. I use a laptop in the field. But cherish those metaphors. Metaphors transform, they make a magician out of you. It goes far beyond the expected role of you as a reporter.

When you’re reporting with this richness, you don’t want the job of transcribing. You can come back from a day’s reporting with 40 or 50 pages of notes if you’re doing your job right, and then you’ll still find you want to put in the article something that you didn’t even have the slightest idea was interesting at the time.

Create translated writer’s notes. Your first draft when you come back with these rich notes is likely to be what I call translated writer’s notes. You go through 50 pages of notes, turning them into a story. Once you’ve done a few of these, you can do that one in your mind. If you do it on paper, you can get your translucent magic marker and circle the hot parts, put them next to each other, and see what happens.

Make a flow notation of scenes. Decide on a rough chronological order. The trouble with outlining narrative is that it tends to shove you towards topicality and the war between chronology and topicality. So I make a sort of flow notation—frequently this scene, this scene, this scene, this scene, and then the purpose of each scene, and then start digressing for topicality and seeing where that stuff fits.

Clean your prose. You cannot have a nuanced relationship with readers unless your sentences are lean, because readers just won’t be able to count on what you’re saying. They won’t be able to count on the nuanced language. You’re making a time sculpture. You’re making a sequential experience for readers that has a contour and a shape and means something. And it’s your theater to create.