When President Dwight D. Eisenhower gave his second press conference on February 25, 1953, Alice Dunnigan was the only black woman accredited to cover the White House.

By Simeon Booker, NF ’51

“Mr. President!” “Mr. President!” “Mr. President!” Associated Negro Press correspondent Alice Dunnigan might as well have been invisible during President Dwight D. Eisenhower weekly news conferences after her questions on civil rights became an irritant to the chief executive. He had called on Dunnigan, the first black female reporter accredited to the White House, five times in 1953, his first year in office, but only twice in 1954, and then years passed before he gave her a nod, finally ignoring her from 1958 until he left office in 1961.

Dunnigan’s persistence, even as the weeks turned into years, eventually drew mainstream press attention (as well as headlines in the 112 black newspapers for which she reported), but no relief. Until 1954, Dunnigan, the only black woman in the White House press corps at the time, was also the only reporter who brought up civil rights issues at Eisenhower’s press conferences. When Ethel Payne of the Chicago Defender joined the White House press in 1954, Eisenhower called on her until her questions, too, always regarding civil rights issues, irritated him. Payne decided to boycott future sessions rather than waste her time. In 1956 and ’57, when school desegregation battles began roiling the South, Louis Lautier, a conservative Republican representing the black newspaper publishers association, was so concerned about provoking Eisenhower’s ire that he twice prefaced race questions by saying he’d been requested to ask them.

Dunnigan’s purdah at presidential news conferences ended on January 26, 1961, when she was the first woman, and the first black reporter, President John F. Kennedy called on—just eight minutes into his inaugural news conference.

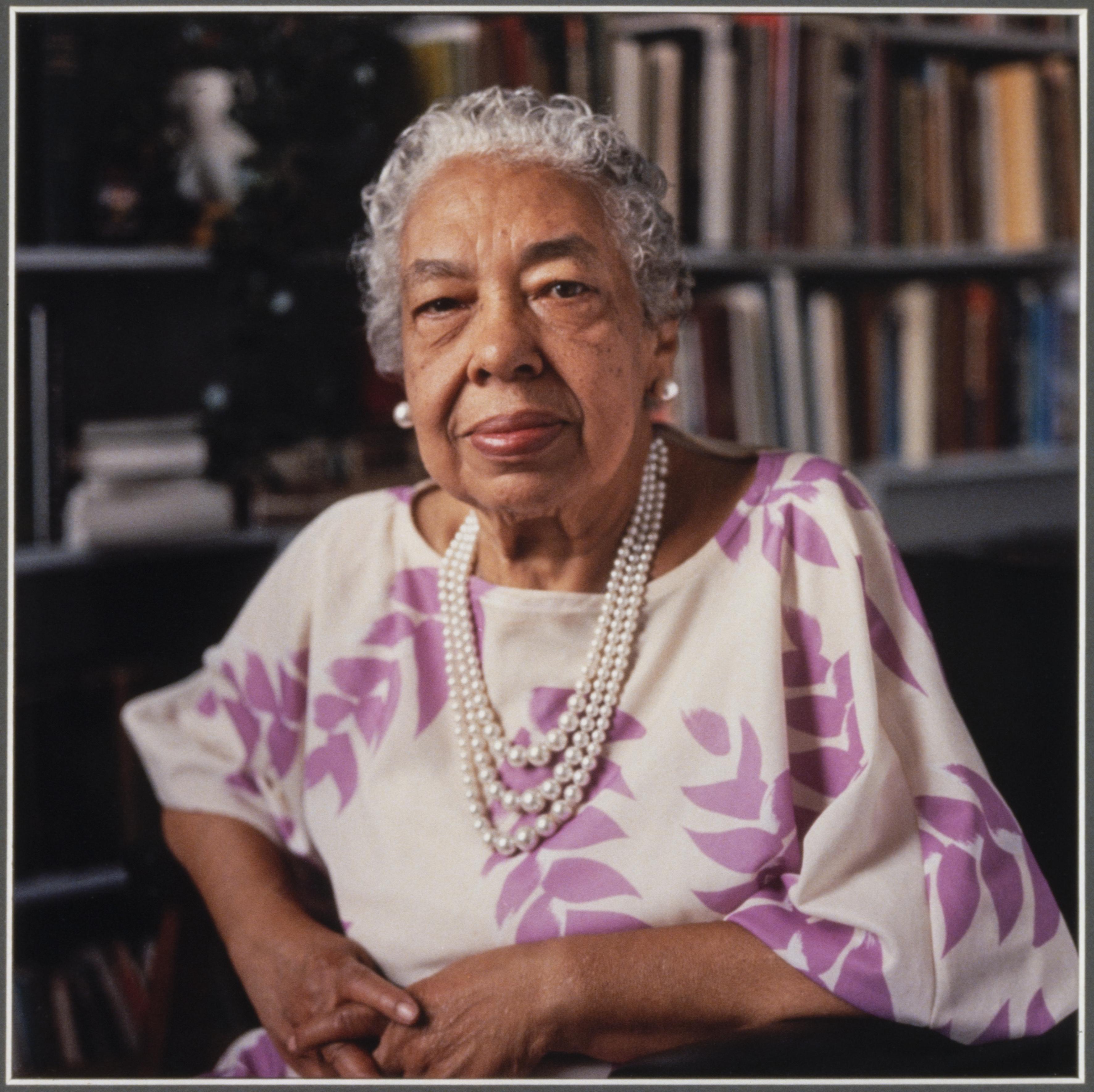

Alice Dunnigan, 1982.

Dunnigan described her face-offs with Eisenhower in a self-published memoir in 1974, which was all but lost over the next four decades. Now her story is available again in an updated, annotated edition, edited by my wife, attorney/journalist Carol Booker, for which I was pleased to write a foreword. In “Alone atop the Hill: The Autobiography of Alice Dunnigan, Pioneer of the National Black Press” (U. of Georgia Press, Feb. 2015), the Kentucky sharecropper’s daughter provides a riveting, unvarnished account of growing up black and female through the Great Depression in this Border State, followed by her war-time arrival in Washington, D.C., and an incredible climb to the highest sanctums of a white-male dominated profession as the first black woman accredited to the White House, the Capitol Press Galleries, and the U.S. Supreme Court. The following is an excerpt in which Dunnigan describes “Eisenhower’s Pique”:

I might say the White House seemed “hell-bent” on gagging me, as far as questions on civil rights were concerned. This became evident at an embassy party, where I was approached by Max Rabb, the president’s special advisor on minority affairs. Over cocktails, in a very pleasant manner, he made a proposition that went something like this:

“Alice, you’re always asking the boss questions on some subject with which he is not familiar. This is very embarrassing to him. Why don’t you check out your questions with me before going to the conferences? Then I will brief him on the situation and he will have a ready answer. All you want is an answer anyway, isn’t it? This way you’ll be sure to get your answer.”

This sounded all right at the moment, and I agreed, but when I gave it more thought, I was enraged because out of the five hundred or more reporters, I was the only one, to my knowledge, who was asked to check her questions with the White House beforehand. But since I had already agreed, I felt I had to go along with it.

Before the next press conference, I called Rabb to tell him I intended to ask the president a question about the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) bill pending before Congress. “Oh, no, no!” he exclaimed. “Don’t ask that question.” Then he went on to explain something about “the boss” working on this measure, and if it were brought to public attention, the southerners on the Hill would take reverse action and throw a roadblock in the president’s plans. This was exactly what I was afraid would happen. I was hurt as well as mad. I sat through the conference “all stuffed up,” watching the white reporters jumping up all around me and asking questions of interest to their readers, none of which provided anything of interest to our publications. It seemed to me that it would have been a breach of journalistic ethics to ask my question despite Rabb’s advising against it. So I left the press conference with nothing of special interest to our readers. I might as well not have been there. I vowed to myself that I would never do it again — never check my questions in advance with anybody on the White House staff — but instead get up like everybody else and ask whatever I pleased.

But it didn’t happen that way. Mr. Eisenhower had a different idea. He apparently had made up his mind never to recognize me again — and he didn’t! I would go to every press conference and jump to my feet between every question, shouting for attention like all the other reporters, “Mr. President! Mr. President!” But Mr. President ignored me. He would recognize people all around me, in front of me, in back of me, on either side, but he always left me standing like the invisible man. The white reporters began to notice the snub, and one day one of them asked, “Do you realize how many times you were on your feet today asking for recognition?” When I replied that I hadn’t counted, he replied, “Fifteen times.”

Another white reporter wrote a story for a chain of newspapers in his state on the Eisenhower snub of a Negro reporter, and Drew Pearson, the nationally syndicated columnist, made note of it in his column. The Afro-American also picked up the story, and a New York radio station called me for a telephone interview. The New York Post called it an attempt by the president to dodge an issue as well as to pigeonhole two women reporters. Labor’s Daily, May 21, 1957, ran a long article on the controversy, stating that I had not been recognized by the president in more than a year and a half, while Ethel Payne (Chicago Defender) had been ignored as well.

There was so much notoriety around the situation that presidential assistant Rabb took to the air to deny that he had requested of certain reporters that questions to be raised at the press conference be submitted in advance for White House approval. In an interview with Tomlinson D. Todd, director of the Americans-All radio program on Washington’s WOOK, Rabb maintained that all questions raised at these conferences were spontaneous and that the president never knew in advance what he was going to be asked.