Eroding Freedoms: Secrecy, Truth and Sources

Among the casualties of the invasion and occupation of Iraq have been truth and trust, according to Sig Christenson, military affairs writer for the San Antonio Express-News. After working as both an embedded and independent reporter in Iraq, he writes about the “propaganda war within Gulf War II,” explaining that “Its roots are in Ground Zero, and I have been a willing participant. So, too, were many other reporters.”

I was consulting at Nowiny (News) in Rzeszów, Poland, when the editor told me that the American embassy had telephoned to ask that I visit Ropczycka, a village of 12,000 near the Russian border, where the local newspaper was having problems.

Zbigniew Dobrowolski, a dark haired, husky man of about 40, met me on arrival in Ropczycka and shared with me his newspaper’s history. It started with the Society of Friends, which was founded in 1939 by Jan Zwierz, a young Catholic priest, to improve the quality of village life. This society could do little during 50 years of occupation by Nazi Germany and Communist Russia, but after the Soviet Union unraveled in 1989, it began holding weekly meetings to discuss public affairs.

One attendee at the meetings was Stanislaw Hulek, a 38-year-old industrial worker, who decided to run for mayor on Lech Walesa’s Solidarity Party ticket. After being elected, Mayor Hulek told the society that Ropczycka should have its own newspaper, and Dobrowolski, a schoolteacher who had once studied journalism, offered to serve as editor without pay. The paper, Ziemia Ropczycka (Land of Ropczycka), would be published monthly. A council was established, with Dobrowolski as chairman and 10 members representative of the village population.

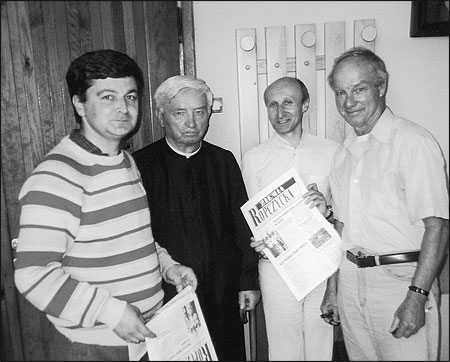

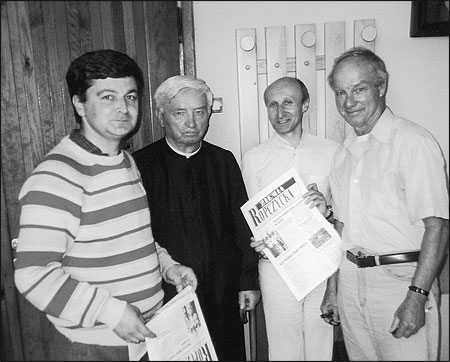

Left to right: Zbigniew Dobrowolski, editor, Ziemia Ropczycka; Father Jan Zwierz, founder of the Society of Friends of Ropczycka; Wojciech Furman, news editor of Nowiny (News) of Rzeszów, Poland, and Watson Sims, consultant.

The Newspaper and the Mayor

The first issue was published in April 1990, and immediately the paper was in trouble with the mayor because of a story involving the village’s medical clinic. Its director had retired and a contest was held to choose his successor. The contest committee selected a popular doctor, but the regional government rejected the nomination without explanation. Ziemia demanded a reason and asked whether it was because the doctor did not belong to the Solidarity Party.

Mayor Hulek, who was a member of Solidarity, asked Ziemia to lay off the story, but the paper continued to demand an explanation. The issue had become a scandal, and the post of clinic director remained unfilled.

In the standoff between the mayor and the newspaper, it appeared that someone telephoned the American Embassy for advice, and I, supposedly an expert on press freedom, was dispatched to try to help resolve the situation.

“Have you given the mayor’s side of the story?” I asked.

“He won’t discuss it with me or my reporters,” said Dobrowolski. “We give him a whole page to use as he pleases, but he won’t write about it.”

Dobrowolski said the mayor continued to attend society meetings, often complaining about the newspaper. He filled the page the newspaper had opened to him with a mixture of cheerful generalities about life in Ropczycka and criticism of Ziemia. He was annoyed by an editorial saying a village as small as Ropczycka did not need two deputy mayors. And when the Falcon Restaurant closed after years of operation, Ziemia deplored despoilment of tradition by new operators who appropriated the name, but Mayor Hulek said any new business in town should be welcomed and urged citizens to patronize the restaurant.

Despite problems with the mayor, Ziemia published eight tabloid pages each month, sometimes generating its own news. One of its projects was a Miss Ropczycka contest, which attracted 50 applicants and presented the winner with one million zloties (about $200). Since Ropczycka had no printing facilities, Dobrowolski drove page layouts 75 kilometers to a printer in Lublin. At 2,000 zloties (about 10 cents), the 3,500 copies of the paper were sold almost as fast as they came off the press. Local advertisers provided support, and the paper was financially sound, so long as no salaries were paid to its workers, including Dobrowolski.

In a meeting with members of Ziemia’s advisory council, I proposed that they seek a meeting with the mayor, since it was he who first suggested the need for a newspaper. Perhaps he could be persuaded of Ziemia’s good will and potential for improving the quality of life for all citizens.

Father Zwierz, who at 88 remained a powerful voice in the society, doubted that a meeting would be helpful, saying the mayor was not politically sophisticated. He said the mayor might stop coming to society meetings and perhaps refuse to fill his page in Ziemia. That would make the task of covering village life even more difficult and perhaps drive the newspaper out of business. Still, Dobrowolski telephoned the mayor’s office, only to be told he would not attend a meeting.

Since the mayor would not meet with us, Father Zwierz suggested that I visit a sugar factory that employs 1,200 workers and is Ropczycka’s most important industry. During a tour of the plant, its director, Roman Krzystyniak, told Dobrowolski, “I did not like that story about the sugar factory. There were many errors.”

“Will you write a letter and give the correct information?” asked Dobrowolski.

“I might,” said the director.

“We try not to make mistakes, and we appreciate letters to the editor,” said Dobrowolski.

“I’ll think about it,” the director replied.

Driving back from the factory, Dobrowolski asked, “What else can I do?”

Remembering some of my own experiences with mayors and business leaders in Battle Creek, Michigan, and New Brunswick, New Jersey, I could only advise him to keep trying. It would not be an easy trip, but press freedom in Ropczycka seemed off to a good start.

Watson Sims, a 1953 Nieman Fellow, is scholar in communications with The George H. Gallup International Institute.

Zbigniew Dobrowolski, a dark haired, husky man of about 40, met me on arrival in Ropczycka and shared with me his newspaper’s history. It started with the Society of Friends, which was founded in 1939 by Jan Zwierz, a young Catholic priest, to improve the quality of village life. This society could do little during 50 years of occupation by Nazi Germany and Communist Russia, but after the Soviet Union unraveled in 1989, it began holding weekly meetings to discuss public affairs.

One attendee at the meetings was Stanislaw Hulek, a 38-year-old industrial worker, who decided to run for mayor on Lech Walesa’s Solidarity Party ticket. After being elected, Mayor Hulek told the society that Ropczycka should have its own newspaper, and Dobrowolski, a schoolteacher who had once studied journalism, offered to serve as editor without pay. The paper, Ziemia Ropczycka (Land of Ropczycka), would be published monthly. A council was established, with Dobrowolski as chairman and 10 members representative of the village population.

Left to right: Zbigniew Dobrowolski, editor, Ziemia Ropczycka; Father Jan Zwierz, founder of the Society of Friends of Ropczycka; Wojciech Furman, news editor of Nowiny (News) of Rzeszów, Poland, and Watson Sims, consultant.

The Newspaper and the Mayor

The first issue was published in April 1990, and immediately the paper was in trouble with the mayor because of a story involving the village’s medical clinic. Its director had retired and a contest was held to choose his successor. The contest committee selected a popular doctor, but the regional government rejected the nomination without explanation. Ziemia demanded a reason and asked whether it was because the doctor did not belong to the Solidarity Party.

Mayor Hulek, who was a member of Solidarity, asked Ziemia to lay off the story, but the paper continued to demand an explanation. The issue had become a scandal, and the post of clinic director remained unfilled.

In the standoff between the mayor and the newspaper, it appeared that someone telephoned the American Embassy for advice, and I, supposedly an expert on press freedom, was dispatched to try to help resolve the situation.

“Have you given the mayor’s side of the story?” I asked.

“He won’t discuss it with me or my reporters,” said Dobrowolski. “We give him a whole page to use as he pleases, but he won’t write about it.”

Dobrowolski said the mayor continued to attend society meetings, often complaining about the newspaper. He filled the page the newspaper had opened to him with a mixture of cheerful generalities about life in Ropczycka and criticism of Ziemia. He was annoyed by an editorial saying a village as small as Ropczycka did not need two deputy mayors. And when the Falcon Restaurant closed after years of operation, Ziemia deplored despoilment of tradition by new operators who appropriated the name, but Mayor Hulek said any new business in town should be welcomed and urged citizens to patronize the restaurant.

Despite problems with the mayor, Ziemia published eight tabloid pages each month, sometimes generating its own news. One of its projects was a Miss Ropczycka contest, which attracted 50 applicants and presented the winner with one million zloties (about $200). Since Ropczycka had no printing facilities, Dobrowolski drove page layouts 75 kilometers to a printer in Lublin. At 2,000 zloties (about 10 cents), the 3,500 copies of the paper were sold almost as fast as they came off the press. Local advertisers provided support, and the paper was financially sound, so long as no salaries were paid to its workers, including Dobrowolski.

In a meeting with members of Ziemia’s advisory council, I proposed that they seek a meeting with the mayor, since it was he who first suggested the need for a newspaper. Perhaps he could be persuaded of Ziemia’s good will and potential for improving the quality of life for all citizens.

Father Zwierz, who at 88 remained a powerful voice in the society, doubted that a meeting would be helpful, saying the mayor was not politically sophisticated. He said the mayor might stop coming to society meetings and perhaps refuse to fill his page in Ziemia. That would make the task of covering village life even more difficult and perhaps drive the newspaper out of business. Still, Dobrowolski telephoned the mayor’s office, only to be told he would not attend a meeting.

Since the mayor would not meet with us, Father Zwierz suggested that I visit a sugar factory that employs 1,200 workers and is Ropczycka’s most important industry. During a tour of the plant, its director, Roman Krzystyniak, told Dobrowolski, “I did not like that story about the sugar factory. There were many errors.”

“Will you write a letter and give the correct information?” asked Dobrowolski.

“I might,” said the director.

“We try not to make mistakes, and we appreciate letters to the editor,” said Dobrowolski.

“I’ll think about it,” the director replied.

Driving back from the factory, Dobrowolski asked, “What else can I do?”

Remembering some of my own experiences with mayors and business leaders in Battle Creek, Michigan, and New Brunswick, New Jersey, I could only advise him to keep trying. It would not be an easy trip, but press freedom in Ropczycka seemed off to a good start.

Watson Sims, a 1953 Nieman Fellow, is scholar in communications with The George H. Gallup International Institute.