When I was growing up in New York in the 1960’s, the only Latinos I routinely saw on television were getting arrested, or Ricky Ricardo. While my hometown was home to more than a million other Latinos, their bylines did not appear in the paper, their names were not heard on the all-news radio stations, and their faces, for the most part, were not on television news.

Things got a little better by the time I started working in entry level editorial jobs in various newsrooms in the mid-70’s. My own duties were largely carried out in seas of white men in white shirts named Dick and Bob. I didn’t know that what I was looking at, as I made coffee, changed wire machine ribbons, and answered the phone, was the end of an era. Through lawsuits and community pressure, occasionally even out of a desire to do the right thing, the doors of local and national newsrooms were slowly being pried open.

But now that we were there—what were we there for?

We could not, in our small numbers, storm the citadels of prejudice and condescension. We could not immediately turn the stick figures representing Latino life we saw in our newsroom output into three-dimensional flesh and blood people. Not yet, anyway.

Now I look back over my shoulder at 25 years in the news business. I have watched affirmative action, one way or another, shape newsrooms. People are hired because of it, in spite of it, and in reaction to its existence. Newsroom managers are either very clear about why it’s important to hire and promote Latino editorial employees, or see it as part of the cost involved in being left alone to do their jobs.

A vast array of organizations—television and radio stations, magazines and daily newspapers, wire services and online publishers—plot across a broad continuum in their motivations and their commitment to a diverse workforce. This makes it impossible to make broad generalizations about the state of play. But here are some observations:

- It takes a long time to move from hiring Latino staff to allowing their presence to actually affect the evolution of your editorial output. The first impulse is to do “Latino stories.” Only later, when it’s realized that there is no such thing as a Latino electric bill, a Latino tax return, or a Latino mass transit system, is full personhood granted, otherness removed.

- Latino journalists are caught between organizational demands that they represent their operation in the community and the community’s demand that they represent Latino interests in the newsroom. Latino journalists must navigate these twin pressures everywhere, from small-market weeklies to national television networks. Often enough, the Latino community and the news operation want a feel-good result to emerge from these efforts, not one that forces all involved to examine difficult truths.

- Until other editorial employees develop a nuanced understanding of Latino life in their market, Latino reporters can expect to be assigned a long list of stereotype-driven stories that follow a couple of main roads: they’re poor…they’re violent…they’re defined by their needs…and, oddly enough, they’re just like you and me.

- Both your newsroom and many community interests want Latino reporters to be publicists, anthropologists, ambassadors and symbols, sometimes more than they want them to be journalists.

- Unless journalists work in a small handful of markets where news stories concerning Latinos are mainstream stories, reporters must straddle their career goals and their zeal for revealing a truer portrait. Reporters will rarely make the top of the show or the front of the book on the “taco beat.” We didn’t sign on to work in a news ghetto, and we’ve got to be very careful that we don’t end up stuck there.

Confused? It’s understandable. Many Latino reporters I’ve spoken with find the cross-impulses a troubling, built-in part of their work. The stories are legion. There are the ones about assignment editors who send the same reporter to the barrio day after day, until one day a big story breaks there and here comes the Big Foot. Then there are the news organizations that fly a Latino editorial staffer like a banner in front of community organizations, only to keep that same employee permanently below the fold in the paper. And, to make the situation tougher, there are the community organizations and leaders who don’t understand why reporters can’t soft-pedal bad news or splash little bits of good news onto the front pages.

Once Latino journalists start to make a little money, they can expect to have their “authenticity” questioned back in the barrios. And, if reporters are constantly trooping out to those same barrios for another feature on quinceañeras, they can expect to be underestimated by their bosses—until they try to break out of the ghetto, at which point their status as “team players” becomes suspect.

The paradoxes don’t end there. For years, we have accepted the notion inside la familia that we have to work harder, be smarter, and make fewer errors than other reporters just to stay even. At the same time as that remains true in many newsrooms, it is also true that Latinos will now also be given the questionable privilege to be mediocre that our Anglo brothers and sisters have long enjoyed. The discomfort comes from trying to figure out whether this really means we’ve “arrived.”

As Jennifer Lopez, Ricky Martin, Benicio del Toro et al. wink out at us from a hundred magazine covers, the news business will engage in catching up to the world of entertainment. Journalists will be located, recruited, hired and over-promoted. They will, on occasion, rise farther and faster than their skills would normally carry them. They will also fail spectacularly from time to time, like Icarus, with no one to watch their backs, no mentor to warn of the nearness of the sun.

This follows a long era in America in which abundantly talented people saw their own career ambitions throttled, derailed and limited by prejudice. A sense of la lucha, the struggle, was a spur to excellence for many. At the same time, the equality that comes with the privilege of mediocrity must be recognized and held at arm’s length.

My advice to today’s young Latino reporters is simple: Be clear about the needs and desires of those who employ you and those outside who see you as helpful to their interests. The difficult part of all this is being clear about who is using whom without surrendering to cynicism and without betraying your fidelity to the standards of your craft. You have the luxury of trying to sort all this out while being the flavor of the decade. You also have the good luck of trying to settle questions of balance, accuracy, portrayal and diversity from inside the morning meeting, instead of from outside on the street with a protest sign in your hand. Don’t underestimate how much has already been accomplished, or how much the people who run the places where we work still have to learn.

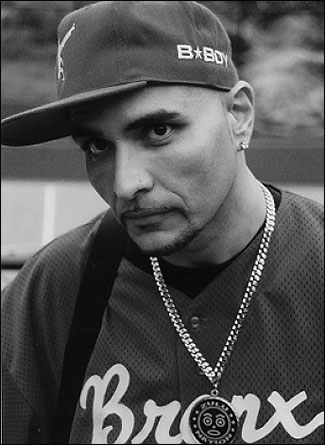

Ray Suárez is a senior correspondent for “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer.” He was the host of National Public Radio’s “Talk of the Nation” from 1993 to 1999, and is the author of “The Old Neighborhood: What We Lost in the Great Suburban Migration” (Free Press).