RELATED ARTICLE

"Bonds of Friendship on an Emotional Journey"

- Joseph Kearns Goodwin When journalists go into war zones, some of them are there to report the news of battles fought, of ground gained or lost, and of soldiers hurt or killed. Others remain with soldiers for a longer time, embedded in their unit, and over time they become embedded in their lives. It becomes their purpose to absorb what it means—and convey what it feels like—to be a soldier fighting this war. Such is the vantage point of author and journalist Sebastian Junger who emerged from his time in Afghanistan with a book called “War” and a companion documentary film, “Restrepo,” co-produced with photojournalist Tim Hetherington. In these essays, we offer the perspective of a soldier who served in Iraq and Afghanistan on how well Junger succeeded with “War” and of a movie critic, Chris Vognar, who writes about “Restrepo.”

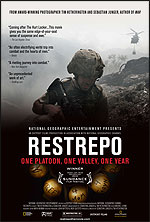

“Restrepo” focuses on the soldiers’ outpost in the desolate Korengal Valley in Afghanistan. Image © Outpost Films.

A platoon patrols a particularly treacherous part of the Korengal Valley, the locus of combat for American troops in Afghanistan. The men know they’ll take enemy fire. We know this too, even as we watch them from the safe distance of Sebastian Junger and Tim Hetherington’s documentary “Restrepo.” But first we all have to wait as the silence builds and builds until it’s ready to break—which, inevitably, it does.

This is the kind of moment that defines “Restrepo” and, by extension, the trust built between the filmmakers and their subjects. As consumers of war films, we are conditioned to see gore and await dramatic climax. But that’s not war. That’s entertainment, the kind that wins Oscars and allows escape.

Junger and Hetherington are after something else. They spent the better part of 14 months with the Second Platoon, Battle Company of the 173rd Airborne Brigade. The filmmakers went on patrols with the platoon. They took many of the same risks, suffered injuries—Junger a torn Achilles tendon, Hetherington a broken leg. They made it clear that they were in for the long haul. So by the time the maddening quiet came along, their presence was taken for granted.

“Restrepo” is more experiential than objectively informative. And part of the experience is the relationship that forms between journalists and subjects when immersion is an option. Call it access, but for these soldiers it was something more. “You build trust,” Jay Liske, a sergeant in the Second Platoon, told me in an interview. “You can open up more and talk about what’s really going on and not be afraid that they’re going to pick and choose the words and make it look like it’s something it’s not.”

Forming bonds of trust also pays dividends once the combat and waiting cease. It’s then time for the men to attempt the near impossible and explain to those who weren’t there what it was like to lose friends, take lives, and fear for their own as they adjust to being back home among civilians. “I’ve been on about four or five different types of sleeping pills and none of them help, that’s how bad the nightmares are. I prefer to not sleep and not dream about it than sleep and just see the picture in my head,” one platoon member says, describing his life in the aftermath of war.

Another foresees his internal struggle as he attempts to figure out how to remember his time at war, a time that others might urge him to try to forget: “I still obviously haven’t figured out how to deal with it inside,” he says. “The only hope I have right now is that eventually I’ll be able to process it differently. I’m never going to forget it. ... I don’t want to not have that as a memory.” He doesn’t say as much, but you get the feeling this soldier is learning to do this even as he speaks about figuring this out.

“Restrepo” brings the war from Afghanistan to us, inviting us to move inside that which we don’t normally even see. The film has been playing at theaters alongside all manner of other movies, and it has been discussed over post-screening beers among friends seeking out Friday night diversion. Sure, we want to understand. But the act of talking about it seems to serve a different purpose for the guys who were there.

“It’s really hard to put it into words and talk about how it feels,” Liske told me. “When people ask what it’s like, we say it sucks. But an actual movie that shows people exactly what we went through and the emotional aspect of it, that’s kind of a weight lifted off our shoulders. We don’t have to explain it to people who have no idea. Now they actually have something to see.”

Documentary filmmakers are recorders and storytellers, not therapists. But Liske hit upon an intangible kind of alchemy on display in “Restrepo,” and it comes back to that sense of trust. Soldiers don’t tell just anyone about their nightmares or the way traumatic memories cling to them. Nor do they tell just any journalist. They confide in someone who’s been along for the ride and has invested the time to burrow deep inside the story.

For the soldiers, it’s trust. For the filmmakers, it’s dedication. And for us, it’s a different kind of war film—powerful, provocative and penetrating.

Chris Vognar, a 2009 Nieman Fellow, writes about movies and culture for The Dallas Morning News.

"Bonds of Friendship on an Emotional Journey"

- Joseph Kearns Goodwin When journalists go into war zones, some of them are there to report the news of battles fought, of ground gained or lost, and of soldiers hurt or killed. Others remain with soldiers for a longer time, embedded in their unit, and over time they become embedded in their lives. It becomes their purpose to absorb what it means—and convey what it feels like—to be a soldier fighting this war. Such is the vantage point of author and journalist Sebastian Junger who emerged from his time in Afghanistan with a book called “War” and a companion documentary film, “Restrepo,” co-produced with photojournalist Tim Hetherington. In these essays, we offer the perspective of a soldier who served in Iraq and Afghanistan on how well Junger succeeded with “War” and of a movie critic, Chris Vognar, who writes about “Restrepo.”

“Restrepo” focuses on the soldiers’ outpost in the desolate Korengal Valley in Afghanistan. Image © Outpost Films.

A platoon patrols a particularly treacherous part of the Korengal Valley, the locus of combat for American troops in Afghanistan. The men know they’ll take enemy fire. We know this too, even as we watch them from the safe distance of Sebastian Junger and Tim Hetherington’s documentary “Restrepo.” But first we all have to wait as the silence builds and builds until it’s ready to break—which, inevitably, it does.

This is the kind of moment that defines “Restrepo” and, by extension, the trust built between the filmmakers and their subjects. As consumers of war films, we are conditioned to see gore and await dramatic climax. But that’s not war. That’s entertainment, the kind that wins Oscars and allows escape.

Junger and Hetherington are after something else. They spent the better part of 14 months with the Second Platoon, Battle Company of the 173rd Airborne Brigade. The filmmakers went on patrols with the platoon. They took many of the same risks, suffered injuries—Junger a torn Achilles tendon, Hetherington a broken leg. They made it clear that they were in for the long haul. So by the time the maddening quiet came along, their presence was taken for granted.

“Restrepo” is more experiential than objectively informative. And part of the experience is the relationship that forms between journalists and subjects when immersion is an option. Call it access, but for these soldiers it was something more. “You build trust,” Jay Liske, a sergeant in the Second Platoon, told me in an interview. “You can open up more and talk about what’s really going on and not be afraid that they’re going to pick and choose the words and make it look like it’s something it’s not.”

Forming bonds of trust also pays dividends once the combat and waiting cease. It’s then time for the men to attempt the near impossible and explain to those who weren’t there what it was like to lose friends, take lives, and fear for their own as they adjust to being back home among civilians. “I’ve been on about four or five different types of sleeping pills and none of them help, that’s how bad the nightmares are. I prefer to not sleep and not dream about it than sleep and just see the picture in my head,” one platoon member says, describing his life in the aftermath of war.

Another foresees his internal struggle as he attempts to figure out how to remember his time at war, a time that others might urge him to try to forget: “I still obviously haven’t figured out how to deal with it inside,” he says. “The only hope I have right now is that eventually I’ll be able to process it differently. I’m never going to forget it. ... I don’t want to not have that as a memory.” He doesn’t say as much, but you get the feeling this soldier is learning to do this even as he speaks about figuring this out.

“Restrepo” brings the war from Afghanistan to us, inviting us to move inside that which we don’t normally even see. The film has been playing at theaters alongside all manner of other movies, and it has been discussed over post-screening beers among friends seeking out Friday night diversion. Sure, we want to understand. But the act of talking about it seems to serve a different purpose for the guys who were there.

“It’s really hard to put it into words and talk about how it feels,” Liske told me. “When people ask what it’s like, we say it sucks. But an actual movie that shows people exactly what we went through and the emotional aspect of it, that’s kind of a weight lifted off our shoulders. We don’t have to explain it to people who have no idea. Now they actually have something to see.”

Documentary filmmakers are recorders and storytellers, not therapists. But Liske hit upon an intangible kind of alchemy on display in “Restrepo,” and it comes back to that sense of trust. Soldiers don’t tell just anyone about their nightmares or the way traumatic memories cling to them. Nor do they tell just any journalist. They confide in someone who’s been along for the ride and has invested the time to burrow deep inside the story.

For the soldiers, it’s trust. For the filmmakers, it’s dedication. And for us, it’s a different kind of war film—powerful, provocative and penetrating.

Chris Vognar, a 2009 Nieman Fellow, writes about movies and culture for The Dallas Morning News.