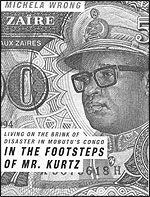

In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in Mobutu’s Congo

Michela Wrong

HarperCollins Publishers. 338 Pages. $26.Not too long ago, if trouble brewed somewhere in Africa, one waited for the announcement over the radio—the continent’s main source of news—indicating whether the country’s radio station had been seized by a rebel faction. The airport was another signal. Due to their importance, whoever ran one or both of them was likely the real power. This was the case between the 1960’s, when most African countries won their independence, and the end of the cold war, when the West applied new pressure on repressive regimes to loosen up on their opponents. This, added to local African dissent—which always existed, if only just below the surface—forced a good number of military and civilian autocrats to legalize opposition parties and relax controls on the media.

To those captivated when power slips away from repressive, corrupt and seeming intractable regimes, Michela Wrong’s book, “In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in Mobutu’s Congo,” will provide good reading. It has a rambling beginning, but the author quickly finds her voice and the narration gets focused. She looks at Zaire, now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which under Mobutu Sese Seko’s rule was one of the most notorious in the bunch. Consulting sources far and wide, she presents a nuanced portrait of the Central African nation and its strongman who described himself as “the all-powerful warrior who goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake.”

Mobutu, a former journalist, led a coup in 1965 when he was the army’s chief of staff, with help from the CIA. The West, in turn, came to his help when necessary and looked the other way during his excesses. Since Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s first prime minister, who was murdered in 1961, was a nationalist with a leftist outlook, Mobutu assured Washington that he would keep the vast, mineral-rich country free from communist control or sheer chaos. He ruled until 1997 and was no ordinary dictator. The graft and plunder of state resources by him and his cronies—in a nation fortunate to have assets like cobalt, uranium, diamonds, gold, copper, timber and oil—was so extreme as to inspire the term “kleptocracy.” Some alleged that Mobutu, a cook’s son, could personally clear his nation’s foreign debt of $14 billion.

He was also wily and ruthless. A successful insurrection from within his army was out of the question. He set subordinates against each other or simply bought them off. And the sensitive positions went to men from his home region. The crisis that finally toppled him didn’t result from his rigging or canceling an election, or attempting to amend the Constitution to allow more time in power, as has recently happened elsewhere in Africa. Rather, what forced him out was a throwback to the old days when an autocrat stubbornly held on to power until an act of greater force brought sudden death or forced exile.

Wrong explains how after the Rwandan genocide in 1994, which was organized by Hutu extremists against their Tutsi countrymen, the Tutsis got control of the country. A quarter of the Hutu population then fled to neighboring countries. The extremists mingled among the refugees. Those who ended up in Zaire started mounting raids into Rwanda after cozying up to Mobutu’s senior army officers.

But what’s particularly interesting is that Wrong shows how the arrival of the huge number of refugees, following the harrowing events in Rwanda, necessitated a major response from humanitarian organizations. Before long, the refugees were enjoying a higher standard of living than the Zaireans. Furthermore, a good amount of money was now being pumped into the refugee areas of Zaire to obtain the necessary humanitarian services, and Mobutu had no control over it. The Zairean economy was in shambles. For instance, the $336 million that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and other aid groups set aside to handle the refugees in Zaire during the last nine months of 1994 was more than the annual operating budget for Mobutu’s government. The country’s elite now saw another source for business deals and survival.

As if this wasn’t enough, the Hutus also began to instigate tensions in eastern Zaire, which has ethnic Tutsis of its own and who have never been on easy terms with the nation’s other groups. The new Rwandan government, already overburdened with the challenge of rehabilitating the country after the genocide, had to do something.

The result was a seven-month-long invasion that exposed Mobutu’s army for what it was: poorly trained and totally incapable of putting up any defense. Starting in the eastern region of a country the size of the United States east of the Mississippi, town after town fell to a coalition of Zairean, Rwandan, Ugandan and Angolan troops, who called themselves the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire. In short, Mobutu’s domestic and regional foes ganged up on him—in an unprecedented fashion for Africa. By May 1997, they had made it to the other end of the country and were suddenly poised to descend on the capital, Kinshasa. By now the West was tired and viewed him as an embarrassing leftover from a bygone era. No rescue was sent. Mobutu finally realized his time was up and fled the country.

Wrong, a British journalist, covered Africa for six years as a foreign correspondent for Reuters, the BBC, and the Financial Times. The book draws its title from Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” the famous novella first published 100 years ago. Kurtz, one of the main characters, is the European ivory trader who goes to the Congo, as a company manager, to make money and introduce civilization. Instead, he descends into extreme savagery. The tale has been interpreted differently over the years and has sparked controversy. Wrong states how she views it: “The ‘darkness’ of the book’s title refers to the monstrous passions at the core of the human soul, lying ready to emerge when man’s better instincts are suspended, rather than a continent’s supposed predisposition to violence.”

The author—to her credit—declines an easier approach that would merely argue that Mobutu was the black substitute for King Leopold II, the Belgian monarch who seized a chunk of African land in 1885 as his personal possession and named it, ironically, the Congo Free State. Leopold then proceeded to ruthlessly exploit it of its rubber, and his mercenary army committed world-shocking atrocities against villagers who failed to meet the extremely high production quotas. International pressure, however, forced him to hand the Congo over to the Belgium government in 1908, which in turn colonized the country until 1960. In 1971 the country, which since 1964 had been known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was renamed the Republic of Zaire.

Wrong does a very good job in exposing how the World Bank and IMF played their own roles in propping up Mobutu. Despite project after project being wrecked by his regime’s corruption, these institutions kept lending money since he was treated as an indispensable Western ally. (Few might know that the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were made with Congolese uranium.) Also, the representatives they posted to Zaire simply didn’t stay there long enough to catch onto Mobutu’s tricks. Each new official seemed to start from scratch in terms of learning the ropes. But there were exceptions such as Erwin Blumenthal, the courageous German dispatched by the IMF to repair Zaire’s central bank. He only lasted a year before throwing up his arms in despair. Nevertheless, his experience, as told by Wrong, is fascinating.

The Zairean economy, according to the World Bank’s own calculations, has now shrunk to the level it held in 1958 while the population is three times as large. Mobutu died of prostate cancer four months into his exile in Morocco at 67. The alliance that knocked him from power broke up and began fighting itself. Laurent Kabila, his successor, who brought back the country’s previous name, was assassinated last year and replaced by his son, Joseph. The government is unable to control major portions of the east and north, which are in rebel hands.

“In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz” is a diagnosis of the system, created against the cold war backdrop that produced and sustained Mobutu at an enormous price to the Congo. Wrong shows there’s enough blame to go around, from Western capitals to his collaborators at home.

Wilson Wanene, a Kenyan-born freelance journalist in Boston, writes on African media and political issues.