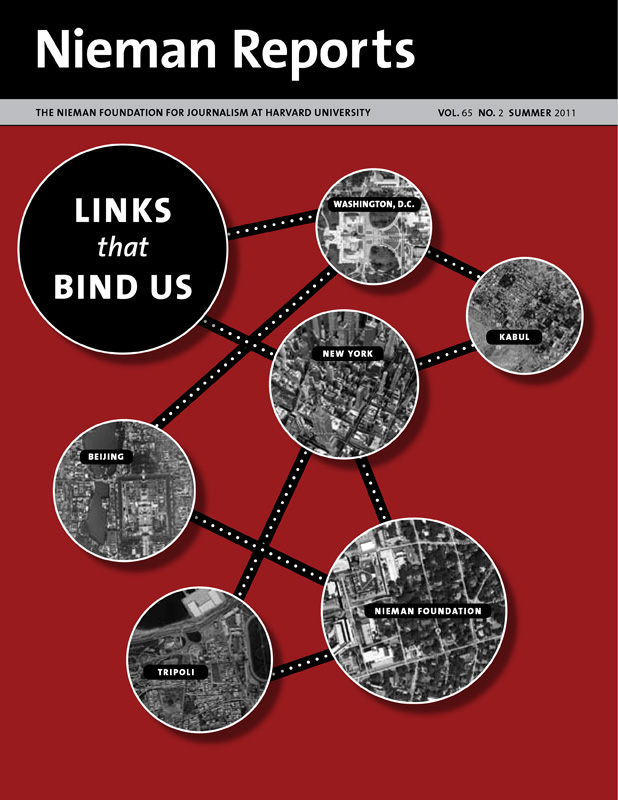

Links that Bind Us

In digital space, journalists are proving to be a powerful force in creating, nurturing and engaging communities. No longer serving only geographic zones, they confront the fragmentation of audience and the need to attract and retain “eyeballs.” Their efforts to embrace and interact with communities are fueled by an instinct to survive. Habits and hobbies, interests and values, political leanings, and sports allegiances are the grist of community formation. Discover the various roles journalists are assuming and how the links we share bind us.

The Greasy Pole contest is a signature event of the yearly St. Peter’s Fiesta that draws together the community of Gloucester, Massachusetts. Photo by Kristen Olson/Gloucester Daily Times.

As this century got under way, Robert D. Putnam's book "Bowling Alone" spoke to the retreat of Americans from organizations and associations that were the bedrock of communities. Club membership was down; fewer people were members of groups or participated in community activities. Putnam described the decline of person-to-person association and activity in terms of communities losing "social capital."

At that time I was a reporter at the Gloucester (Mass.) Daily Times, a community newspaper. I found out about "Bowling Alone" when my editor wrote about Putnam's ideas in newspaper editorials. Putnam's research did not focus on newspaper readers per se, but he did illuminate a few important things to know about their habits and lifestyles. To start with, newspaper readers were 10 to 20 percent more inclined to participate in their communities. Putnam described them as people who "belong to more organizations, participate more actively in clubs and civic associations, attend local meetings more frequently, vote more regularly, volunteer and work on community projects more often, and even visit with friends more frequently and trust their neighbors more."

Even so, Putnam did not frame reading a newspaper as a building block in a community's social capital. Perhaps this is because, like voting, reading is a solitary act and does not forge a direct personal connection. Putnam expressed uncertainty about whether reading a newspaper was a trait shared by those engaged in civic life or if reading the paper somehow prompted people to participate.

In some ways, it doesn't matter. Newspaper readers are a life force in producing a healthy, more vital community. And maybe it's hubris from my time working on various community newspapers, but I think of a newspaper as an important force in creating social capital. It is the community's common denominator, and as such it makes connections among people whether it wades into a controversy or reflects a shared tradition. At the Gloucester Daily Times, I am convinced our stories prompted people to gather at local meetings, to reach out to neighbors in trouble, and to more deeply appreciate their heritage.

With wall-to-wall coverage, the Daily Times pays tribute to the importance of St. Peter’s Fiesta in the lives of Gloucester’s residents. Photo by Mary Muckenhoupt/Gloucester Daily Times.

Covering Tradition

RELATED LINK

Read the Gloucester Daily Times's coverage of the 2011 Fiesta.In Gloucester, no community tradition is as rich in history and symbolism as St. Peter's Fiesta. Every June, the country's oldest seaport, founded in 1623, celebrates its fishing fleet and the patron saint of fishermen. This tradition dates to 1927, after Captain Salvatore Favazza commissioned a statue of St. Peter for the immigrant community.

Long ago this Italian community branched out beyond the Fort neighborhood of triple-deckers bounded by Gloucester Harbor and fish plants, but every year the fiesta returns to its streets. Timed to the Catholic feast of St. Peter, the fiesta features reunions, open houses, and revelry that continue late into the night, with a predictable itinerary of athletic events borrowed from old world villages. It's the Greasy Pole contest that gives this event its iconic image as groups of rowdy men assemble on a platform in Gloucester Harbor, each walking a slicked wooden spar jutting over the water. The goal is to stay upright long enough to grab a flag staked to the pole's end. Spills onto the pole and into the harbor below can be brutal.

The fiesta has endured even as the city of about 30,000 people has changed. Still isolated and fiercely independent, Gloucester has evolved into a blend of a working-class port with professionals, artists and tourists. This summer festival has spread beyond an immigrant community to leave its mark on everyone in the city.

Ever since I began as a reporter at the Gloucester Daily Times in the late 1990's, coverage of this event was planned well ahead of time. The playbook is as worn as the one used for local elections. I took turns writing about boat races and the Sunday procession that winds through downtown following a Mass and the Blessing of the Fleet, usually celebrated by the Catholic archbishop of Boston.

This assignment—more reactive than proactive—was a summer ritual, a long and tiring weekend of work that ended when revelers gathered at midnight Sunday to hoist the 600-pound statue of St. Peter for one last trip through the Fort neighborhood, where I happened to live.

With its coverage, the Daily Times was not so much building or leading the community as it was reflecting through names and faces the memories of past generations and stories of the present. All enriched the community's experience.

Community Connections

My notions of what it means to do community journalism were shaped, in part, by the role I played in telling fiesta stories and knowing how much they meant to those who inhabited this place. Ingrained in me from this experience is the sense that a successful community newspaper—or local blog, website, Twitter feed, or any other communication tool—is much more than a vehicle that conveys information.

To publish a calendar of events or a police log is simple. Community journalism assumes its value in finding ways to connect people—by identifying passions and concerns they share, linking neighbor to neighbor, and motivating people to act. It also serves a vital purpose when it takes on tough, controversial issues and tells stories that lead to the discovery of fault lines within a community.

During my career at the Gloucester Daily Times—five years as a reporter and two as its editor—my focus often was on stories about development or the fishing fleet's perpetual struggle against tightening government policy. Both story lines involved the environment and conservation groups and both frequently incited controversy among neighborhood groups, activists or fishermen.

Experiencing such reaction is gratifying, and I fear it is diminishing. Knowing the difficulties many of these local papers face, I worry that as newspaper readership declines and newsroom staffs shrink, communities will be left uncovered, at least by journalists whose job it is to know what keeps the heart of the community pounding. In some instances, hyperlocal websites or blogs are emerging, and some will serve this function, in part if not in whole. But the trend in these digital shops—as in legacy newsrooms—is to devote fewer resources to newsgathering, not more.

That is a stark contrast to the pages of the Gloucester Daily Times every June, when the newspaper serves the community in its comprehensive coverage of St. Peter's Fiesta. Year after year stories, images and personal anecdotes engaged the community, in print and now online, and the newspaper benefited, as well.

In the fall of 2003 I returned to the Daily Times as editor of the paper after I spent a year at a sister paper. By the next summer the fiesta held heightened significance as we felt our newspaper's connection to the community slipping. The paper had a history of deep readership penetration in Gloucester and the surrounding towns, but we'd ruffled readers with a redesign. A change in press deadlines was forcing us to report news on a different cycle. People in the community were generally suspicious of our new owners. Circulation was bleeding like air seeping from a tire.

RELATED LINK

The Gloucester Times reports on efforts to rebuild the Greasy Pole after it was damaged in a storm.Our Monday-after-fiesta edition was always packed with coverage of the Greasy Pole, Blessing of the Fleet, and religious procession. (The Daily Times publishes Monday through Saturday so the bulk of weekend happenings are reported on Monday.) That year we felt a special need to deepen our fiesta coverage so we decided to ignore all other news on June 28, 2004, giving Page One and two other section fronts to the fiesta. It turns out that we published only three stories unrelated to the fiesta, not counting a package of sports briefs and a Little League roundup.

Such wall-to-wall coverage might have been excessive. That day's newspaper sold well, as I recall, as did most post-fiesta editions. But this wasn't so much a sales ploy as it was a symbolic statement: Just as St. Peter's Fiesta and Gloucester are inextricably linked, so are the fiesta, the city, and its local newspaper.

David Joyner was a reporter and editor at the Gloucester Daily Times, then managing editor at The Salem News and The Eagle-Tribune in North Andover. He is now vice president of content for Community Newspaper Holdings, Inc., which owns all three Massachusetts newspapers. In the fall, he joins the Nieman Class of 2012.