The Search for True North: New Directions in a New Territory

In this time of accelerating change, how journalists do their work and what elements of journalism will survive this digital transformation loom as questions and concerns. By heading in new directions and exploring the potential to be found in this new territory of interactivity and social media, journalists – and others contributing to the flood of information – will be resetting the compass bearing of what constitutes “true north” for journalism in our time.

It was 10:30 a.m. on Thursday, July 31st, when the bombshell dropped. At a standing-room only gathering of The Star-Ledger’s staff, publisher George Arwady stepped onto a riser and said the newspaper, after years of losses, was in deep distress. The largest paper in New Jersey, he said, needed to obtain 200 voluntary buyouts and to renegotiate contracts with two unions. If these conditions were not met by October 1st, the newspaper would be either sold or shut.

As employees headed solemnly back to their desks, one small crew from the newsroom was already wrestling with the implications of the announcement. Just three days earlier, the newspaper had launched a noontime Web cast called “Ledger Live.” Like many of our other digital efforts, it was designed to reach new audiences and—it was fervently hoped—to help the company’s bottom line.

But now?

“Breaking news this morning from The Star-Ledger, about The Star-Ledger,” host Brian Donohue told viewers when the cameras went live an hour later. “The state’s largest newspaper is, and I quote, ‘losing a battle to survive.’” Without embellishment, he laid out the conditions described by the publisher and noted that the news had left “a lot of people walking around here … pretty stunned.”

Radical Change

Welcome to newspaper innovation, 2008-style. Faced with steady circulation losses and rapidly deteriorating ad revenue, newsrooms across the country are moving swiftly, if belatedly, to retool and refocus on digital content and delivery. But they are doing it with an existential question pointed like a gun at their heads: Will it all be enough to halt the slide and save the business?

In some cases, the answer will probably be no. Mark Potts, a consultant and entrepreneur who helped overhaul philly.com earlier this year, wrote recently of daily newspapers that “sometime in the next few months we’re going to lose one—or it is going to be changed so radically as to be barely recognizable under the current definition of daily newspaper. And given the lemming-like tendencies of the newspaper industry, once one newspaper goes, others will quickly follow.”

The truth, of course, is that the definition of daily newspaper is already barely recognizable, at least in terms of newsroom workflows and relationships with local communities. At The Star-Ledger, nightly print deadlines are just one station stop in each 24-hour news journey, and increasingly our Web site, nj.com, is a platform not just for the delivery of content but for meaningful engagement with users.

Like many of our peers, we have made these radical changes in practice and culture in a hurry, creating new products and new business models on the run. This revolution has touched every aspect of what we do, but maybe nothing illustrates the pace and extent of change as well as our video efforts—and, specifically, the creation of “Ledger Live” in the days before the reality of the newspaper’s plight became so painfully clear.

Learning Video Journalism

“The business of newspapers is to go into the community, find stories, and publish them. As newspapers move to the Internet and the Internet concurrently moves into video, it is incumbent upon newspapers to begin to embrace video as a means of newsgathering and storytelling.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"Video News: The Videojournalist Comes of Age"

- By Michael RosenblumThose two sentences were the opening lines of a proposal made to The Star-Ledger in January 2008 by Michael Rosenblum, the firebrand consultant who over the years has helped to create New York Times Television and the NY1 cable news station, among other notable projects. At The Star-Ledger, Rosenblum hoped to engineer a seismic event, changing the way newspapers think about video—and about news coverage in general.

As it happened, Rosenblum’s ideas meshed perfectly with the goals of editor Jim Willse, who for years had seen opportunities for video in a state without its own network TV news outlet. Bracketed by the New York and Philadelphia markets, New Jerseyans have grown accustomed to seeing local news on television in only the rarest of cases and usually when calamity struck. The idea of filling this void held enormous appeal.

So it was that Rosenblum, dressed as usual in head-to-toe black, arrived with his team in The Star-Ledger newsroom on a pleasant Monday in late May to train 20 people how to tell video stories and, in the process, lay the groundwork for launching a five-minute noon Webcast in a matter of weeks.

The group of trainees included reporters, photographers, editors and a graphic artist. Everyone had volunteered, along with more than 80 other staffers from a newsroom of about 330, and had been selected after shooting a three-minute tryout video. Each arrived equipped with a high-definition Sony video camera and a MacBook Pro laptop loaded with Apple’s Final Cut Pro editing software (at a cost of about $7,000 per kit, including all accessories).

We spread the training across different departments partly to share the workload, but mainly because we wanted video to become part of who we were as a news organization and how we thought about everything we did. As Rosenblum noted on more than one occasion, we were aiming to “change the vocabulary of the reporting” to embrace a multimedia, multiplatform approach to local news and information.

Over the course of five long days, fueled by coffee and doughnuts and a lot of enthusiasm, the group learned how to shoot and edit complex video stories. Looking back now, it’s clear we were only just beginning, but it’s still pretty remarkable how good some of those first stories were—and most were shot, narrated and edited by people who had never picked up a video camera before their tryouts.

A big reason for the immediate results, I think, was that the room was filled with journalists who knew already how to tell stories; they merely needed the tools and training to translate those stories to video. But it had a lot to do with Rosenblum’s method, too, and especially his insistence on simple techniques: think before you shoot, decide what you need, shoot only what you need, and for crying out loud don’t move the camera while you’re shooting. Oh yeah, and no stand-ups with blow-dried “talent.” Just good visual stories, shot up close and tightly edited.

Everyone who went through the training left with a responsibility to produce one video story each week. And everyone was given one day each week to do it. To manage all this, we created a couple of important new positions: an assistant managing editor for video and a video enterprise editor, who together coordinated the activities of our 20 new video journalists and edited the work they produced.

Suddenly, our Web site came alive with videos about urban drug addiction, suburban wildlife management, cancer survivors, glass-blowing artists, taxi drivers, and taxidermists. On big news stories, we produced deeper and more timely video coverage than the New York and Philadelphia TV stations. And day after day, right from the start, we offered a steady diet of enterprise stories and news clips that you couldn’t find anywhere else.

We had the goods for a pretty decent daily show. Now we just had to figure out how to do live TV.

Going Live

Why live? Why not just record the segments and slap everything together in postproduction? Certainly that would have been the safer route, allowing greater quality control and ensuring more consistent production values—which is really just a nice way of saying we’d be less likely to make fools of ourselves. Why not learn to walk before leaping onto a high wire?

For us, the reasons were pretty basic: We did not want to produce an imitation of local TV news. We wanted to create something far less polished—more like a video blog, short and raw and conversational. If we could edit things after the fact, we figured, we’d probably squeeze the life out of it. There was also the matter of efficiency: A five-minute live show takes five minutes to produce, every time. No postproduction, no do-overs.

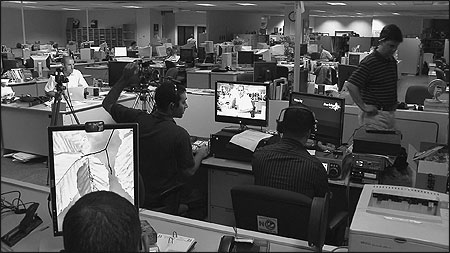

The technology was the easy part. Two cameras, three overhead lights, four monitors, a switcher, a graphics deck, a recording deck, a digital encoder, and—voila!—we had a set in the middle of the newsroom equipped to produce a multicamera live show for the Web. It took practice and dexterity to run it all, of course, but that was nothing compared with the job of figuring out what exactly we wanted the show to be.

Was it a straight news show? That didn’t work, because text headlines are a far more efficient way to catch up with news in a hurry. Was it a variety show? That didn’t seem to play to our strength as the state’s largest newsgathering operation. We settled finally on a hybrid, with a twist: Quick headlines at the top when there was fresh news, a couple of Jersey-centric videos, and a constant effort to involve bloggers, vloggers and podcasters from across the state. The show would be short, original and as interactive as possible.

We played around with a TelePrompTer, then realized it was killing the sense of spontaneity. We noodled with slick intro packages, then decided we were getting too fancy. We looked across the room for a central-casting brand of anchor, then picked a veteran beat reporter who wouldn’t be caught dead in make-up but had a knack for talking about the day’s news in a way that made you feel as if you were sitting on the edge of his desk, chatting.

So with Brian Donohue in the host’s chair and two technical wizards, Seth Siditsky and Bumper DeJesus, running the switcher and producing in-show graphics, we started making two pilots each day, one at noon and another at 5 p.m. We did this for the better part of a month, blowing our original deadline of a July 1 launch because we were determined the whole process should feel like second nature before we started for real.

We made a lot of mistakes and learned from them. We repeatedly switched to the wrong camera between segments and worked on set direction until we got it right. We realized we couldn’t expect Brian to remember every detail of a complicated story without a TelePrompTer, so we taped notes with key names and numbers beneath the camera lens. And we learned the hard way that we needed to unplug Brian’s desktop phone before going live.

RELATED WEB LINK

Ledger Live

- www.nj.com/ledgerlive/On Monday, July 28th, just nine weeks after the first day of the Rosenblum boot camp, we officially launched “Ledger Live,” believing we were helping to shape, in our own small way, the future of New Jersey’s largest news organization. As the cameras started rolling, Brian smiled and delivered his now-standard greeting: “How ya doin’, Jersey. Welcome to the Star-Ledger newsroom.”

This was a newsroom that, just three days later, would be wondering if it had a future at all.

The show received some nice early reviews from a wide range of places. Frank Barth-Nilsen of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation called it “perfect for mobile journalism, bringing news back fast from the streets of New Jersey.” Ryan Sholin of GateHouse Media said it was “the best newspaper webcast I’ve seen yet.” Others were less kind. Don Day of Lost Remote described our effort this way: “Another newspaper launches another boring webcast.”

The reaction to “Ledger Live,” though, held far less interest for those of us working on the show than did the life of the Ledger. In the worst-case scenario, the newspaper would be closed, and all of our work would have been for nothing. Even in the best of outcomes, there was a chance we’d lose some or all of the talented people who made the show possible. In the meantime, we had a show to make five days a week.

When the dust settled, The Star-Ledger’s owners got the union concessions they sought and received more than the required number of buyout applications—including, after weeks of painful deliberation, mine. The result was a reduction of newsroom staff in the neighborhood of 40 percent.

The newspaper lived to fight another day, providing a little breathing room to find the innovations that might secure its future. The existential question had been answered, at least for the moment, allowing the “Ledger Live” team—still intact, somehow—to focus on finding its place in the world.

Can a newspaper turn video into a profitable business model? Can a daily news show made for the Web build audience and compete for advertising dollars with established network and cable TV? How can a show such as “Ledger Live” help change the relationship between the newsroom and the community it serves?

The jury is still out on all of this, but a few things are clear. Newspapers have the talent to do new and innovative things in the digital sphere, and they still have the reporting resources to deliver a depth of coverage that is unmatched in most markets. The future belongs to those who are willing to experiment, to evolve, to fail quickly when they do fail and to move on, even as disaster waits at the door.

John Hassell is the former deputy managing editor/digital for The Star-Ledger of Newark, New Jersey.