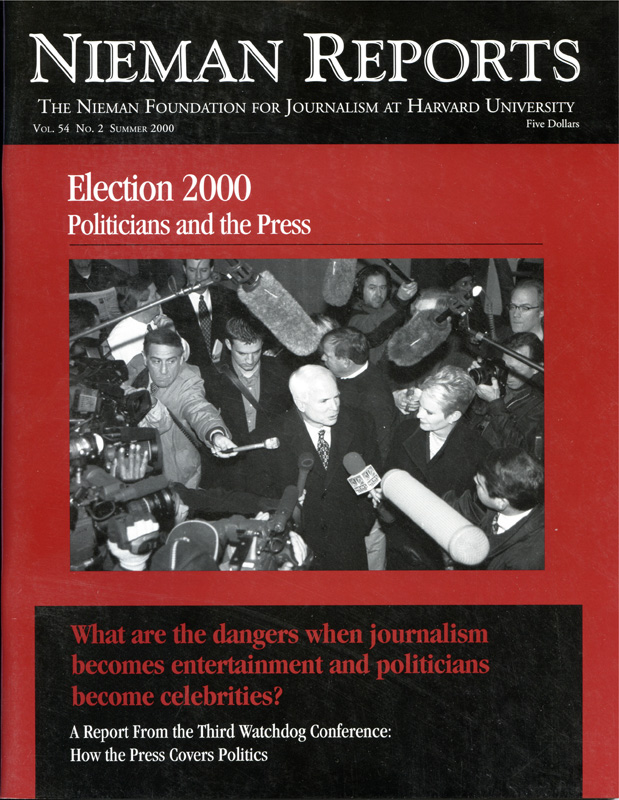

Bill Bradley and John McCain joke after jointly endorsing campaign finance reform in Claremont, New Hampshire. Photo by Reba Saldanha.

Every presidential campaign has an issue or two popping up and surprising us. In the 2000 presidential primary season, the Cinderella issue was the political influence of money.

Here’s an issue beloved by few—mostly good government groups and newspaper editorial boards. Poll after poll has shown that the phrase “campaign finance reform” doesn’t stir voters’ civic souls; it makes them want to yawn. Politicians have maintained a Mafia-like omerta when reporters start asking how campaign cash materializes and, heaven forbid, how it might influence the donor-recipient relationship. As an aide to a House leader once said, explaining why I couldn’t get in to see her congressman work the crowd, “We know what kind of stories you do. You do money stories.”

But for a time this winter, it seemed that nobody on the campaign trail could stop talking about money, and not just on John McCain’s Straight Talk Express. It was all about soft money—the unregulated contributions from corporations, unions and millionaires that, in the 1990’s, came to dominate American politics. McCain, of course, wants to make soft money illegal. Going back to last summer, when the Express was a dirty blue rental van, he managed to transform soft money from an everybody-does-it non-issue into a question of character. The way candidate and voters discussed it, there seemed to be only a thin line separating Clinton-style fundraising and other Clinton-style misbehavior.

Former Senator Bill Bradley was working the same argument, if less effectively, and other candidates caught on. Vice President Al Gore—he of the Buddhist temple fundraising and “no controlling legal authority”—became a repentant sinner, promising to dismantle the money system he and President Clinton worked so hard for four years ago. Texas Governor George W. Bush was “a reformer with results,” even though he’d previously dismissed political money as an insignificant issue. Challenged by McCain’s soft money ban, Bush tried to split the difference by declaring soft money from corporations and unions bad, but soft money from millionaires good. Even Gary Bauer and Alan Keyes—candidates destined never to smudge the ink on a newly written six-figure soft money check—felt obliged to stake out positions.

Gradually, reporters realized they no longer had to crank out the once mandatory “What is soft money?” sidebar.

Political scientist Diana Dwyre, coauthor of an upcoming book on the battle over campaign finance reform, says media coverage of political money will never be the same. “I think that we’re going to have a lot more discussion, and a lot more watching of the whole soft money game this time around,” says Dwyre, a political scientist at California State University at Chico. “Before, I think people [in the media] were trying to figure out what is this stuff, how is it spent, what’s an issue ad, why is it considered to be sort of on the edges of law.”

Now, says Dwyre, “Every reporter understands what soft money is.”

The money-and-politics boomlet isn’t the doing of a single ambitious and engaging senator from Arizona. The past decade has seen accelerating changes in the way the beat is covered. Money-trail stories that once were a mainstay of a few investigative magazines now appear regularly in daily coverage. And it doesn’t take an I-team to identify the biggest reason why: computers and the Internet.

Ten years ago, I started my first big campaign finance story—a look at the state-level political action committees run by some members of Congress. We called them “back-pocket PAC’s” (political action committees run for the benefit of a federal candidate or candidate-wannabe). Now, as they’ve proliferated, they’re commonly known as “soft money leadership PAC’s.” Whatever you call them, they let lawmakers get around those irritating disclosure mandates and fundraising limits in Washington.

Back then, just locating these PAC’s took weeks of legwork. An official at the Federal Election Commission [FEC] shared an informal list of leadership PAC’s. Armed with the list, I started calling state capitals. Most states had little or no PAC disclosure. Those that did wanted a check in the mail before sending off photocopies.

RELATED ARTICLE

“Money and Politics on the Web”Today, most of that story can be done online. Some Web sites let you aggregate contributions that a donor might spread around to a politician’s various committees. Others collect data from state campaign finance agencies.

Still, political money coverage shouldn’t be considered an indoor sport. Tracing the money trail from the donors remains only the first step, to be followed by document searches, coverage of fundraising events (especially those closed to the press), plus interviews and more interviews. On the other sides of the money-and-politics equation, political committee spending data and lobbying records are only slowly finding their way into online databases.

And many of us still are not savvy, aggressive and insightful with the data and other information that we are now able to amass. People inside and outside of journalism describe the beat interchangeably as “campaign finance” and “campaign finance reform.” The two phrases aren’t synonymous, of course; one is reporting, the other is advocacy. But it seems the more a journalist thinks of the beat as “campaign finance reform,” the more he or she moves into gotcha journalism.

Take the story of McCain’s relationship with Paxson Communications. The senator accepted money contributions and cut-rate rides on the Paxson corporate jet. Paxson got McCain’s successful effort to force the Federal Communications Commission to vote on the buyout of a public TV station—a vote that went in Paxson’s favor. After The Boston Globe broke the story, the big question was whether it made McCain a reform hypocrite. Few of us spent much time chasing the systemic question: Why does election law allow CEO’s to underwrite political travel?

It’s a sweet little loophole, benefiting candidate and CEO alike, and all for the cost of a first-class ticket. Most of us—me included—gave short shrift to two facts: first, that McCain was hardly the only presidential hopeful flying the friendly corporate skies, and second, that the loophole permits what amount to in-kind soft money contributions directly to the candidates. (Regular soft money operates under the fig leaf that contributions go to the party committees rather than to candidates themselves.)

Or take the matter of George W. Bush’s online financial disclosure. Last September, the campaign put its donor records onto its Web site. It quoted the candidate as saying: “Americans will be able to look for themselves to find out who is helping to fund my campaign.” The press release was headlined: “Governor Bush takes lead on campaign finance reform.”

Is this real reform? Aside from the philosophical question Bush posed (there’s anecdotal evidence that disclosure minus reform makes voters more cynical), journalists ought to question the quality of Bush’s disclosure. The Web site permits searches only by donor’s name, dollar amount or date. You can’t do the three types of searches essential for any real analysis of where the money comes from: a donor’s occupation, employer and location. For that information, interested parties still have to wait until Bush files with the FEC—just like all the other candidates.

As the primary campaign segued into the general election contest this spring, we suddenly seemed to be right back where Campaign ’96 had left us—listening to a shrill debate over reform, conducted by two candidates who’d avoided the issue until outside forces pushed them into embracing it. In 1996, conventional wisdom held that voters couldn’t care less, and as the Democratic fundraising scandal spawned investigations and hearings, our coverage came to reflect that jaundiced view. By the time Senator Fred Thompson gaveled the first hearing to order, the scandal story line has been replaced by one focused mostly on partisan strategy and spin.

This time around, a newly emerged constituency of McCain and Bradley voters demonstrably does care. So while we on the political money beat pore over our databases and study lobbyists’ disclosure forms, there is another question to consider. Will reporters, editors and the public tire of this new emphasis on big money’s political influence?

Or did the 1996 campaign turn us toward a new, Mark Hanna-based style of political coverage? It was Hanna, the engineer of William McKinley’s political career, who said 105 years ago, “There are two things that are important in politics. The first is money, and I can’t remember what the second one is.”

Peter Overby has been covering money and politics for 10 years. In 1994, he became the first reporter on National Public Radio’s power, money and influence beat.