Kate Sosin and Nico Lang landed in Anchorage in March 2018 and got into a Lyft to their hotel. The Lyft driver asked what the pair was doing in town.

“I was stupid enough to say, ‘Oh, we’re reporters,’” Sosin recalls. They told the driver they were there to report on Proposition 1, which would have required trans people to use the bathroom or locker room associated with the gender on their birth certificate. Turns out, bringing it up was a mistake.

“He started spouting off all of this transphobic rhetoric about how ‘we’ didn’t want men in women’s bathrooms,” Sosin says. As a trans journalist, Sosin found it a nerve-wracking introduction to Anchorage, where they’d come to report for the week leading up to the city’s historic vote on the measure. These so-called “bathroom bills” are predicated on the myth that trans women are predatory men masquerading as women. Sosin and Lang were both staff writers at Into, the national LGBTQ outlet associated with the gay dating app Grindr, and they pitched the story because they believed Anchorage was a bellwether.

Sosin says their editor at Into was affirming and supportive, quickly agreeing to assign multiple features on the topic. Sosin and Lang produced in-depth coverage on the lead-up to the vote and the outcome, both during and after their trip to Alaska.

Sosin’s trans identity often made it easier to connect with sources and to tell stories that were deeply reported and empathetic.

“They found all these different access points for people reading this story,” says former Into managing editor Trish Bendix, who is a cis queer woman. “There’s a way to make these stories, like any story, find some central human interest point, and I think that Kate can balance that with making sure that it’s still very centered on trans people and trans issues.”

As we become more visible, trans journalists are asking journalism leaders to confront the structural barriers that make it hard for trans people to enter and remain in the industry

For example, an article about community organizers coming together against Proposition 1 included drag kings, leather daddies, and climate change activists who brought an anti-Proposition 1 banner to the Iditarod, the annual long-distance sled dog race. Sosin and Lang focus on trans people while including the stories of straight and gay allies, who all rallied together to defeat the ballot measure.

Transgender journalists in the United States are a small but growing group. As we become more visible, trans journalists are asking journalism leaders to confront the structural barriers that make it hard for trans people, particularly trans people of color, to enter and remain in the industry. We are also pushing cisgender editors to be more cautious and accountable in their coverage of gender issues. Still, there are very few trans people in leadership positions, a reflection of the many obstacles trans journalists still face.

In just the last couple of years, the number of out, visible transgender journalists and editors has increased noticeably. Queer outlets like Into and them, a Condé Nast website focused on culture, employ a bevy of trans writers and several trans editors. Raquel Willis took the helm as executive editor at Out magazine, a gay fashion and lifestyle magazine, and trans journalists now have a prominent collective presence on Twitter, a private Facebook group, and various other private networks.

Trans writers have been outspoken in favor of hiring trans people to cover LGBTQ issues and have a growing collective voice in critiquing inaccurate and insensitive coverage, which has implications for newsrooms that have long been covering transgender issues without the visible presence of trans writers. Trans people often bring connections and insights that are very different from their cisgender editors and colleagues, including a tendency to question traditional “objectivity” in the newsroom. The recent resignations of two trans employees at The Guardian have highlighted the challenges and tensions. For those seeking a trans writer, it is easier than ever to tap into networks of trans journalists via social media.

Despite the structural limits to trans people entering journalism, these efforts have begun to have an effect. In 26 states, it’s still legal to fire or not hire someone for their gender identity or expression, and the effects of anti-trans discrimination don’t fall evenly across the community. Trans women of color are disproportionately likely to live in poverty and to face violence; trans people overall have a high risk for homelessness and suicide. And many people of color and poor and working class people (trans or not) can’t access the education, social capital, and other forms of preparation and connections that allow them to enter the field and advance to leadership positions.

Trans journalists who do break into the industry face a slew of challenges if they are out on the job: questions about health care access, discriminatory treatment, microaggressions from colleagues and sources, tokenism, frequent misunderstandings of trans issues from editors, and challenges with going through legal name and gender changes. That said, it appears the presence of trans people in newsrooms is beginning to move the needle in terms of the quality and quantity of trans coverage.

Sosin didn’t initially see themself as a “trans reporter.” Born and raised in the Chicago area, they started reporting while visiting Haiti in college, telling stories about communities that were not their own. Then they worked for several years at Chicago’s Windy City Times, and after that about a year and a half at The Boston Courant, a hyperlocal print paper that covered affluent areas of Boston. Sosin wasn’t intentionally in the closet, but says their identity as a nonbinary trans person was so marginalized that they effectively were. Their boss once even said to them, “I wouldn’t want to use the same bathroom as you,” Sosin says, which they took to imply that they, a nonbinary and masculine person, were too womanly to share a bathroom with a man.

“That is the job that sort of ended journalism for me,” Sosin says. Sosin felt it was too hard to find a job where they could get paid enough, be respected, and also be out about their identity.

Working at Into helped Sosin realize the importance of queer media. “I felt like they actually really valued the identities of their reporters,” they say. “Mainstream journalism just does the opposite. Into was so respected because it empowers writers to tell stories about their own communities.” Sosin’s coverage of the anti-trans initiative in Alaska is a good example of that.

Former Into editor Bendix says that creating a trans-affirming environment for reporters requires a proactive attitude. “As editors, the people making the decisions, you have to be not just willing, but you have to be the ones saying, ‘Yes, this is how we should be evolving,’” she says. She gives the example of integrating they/them pronouns or using terminology that may be familiar to trans people but is uncharted territory for many mainstream publications. “You have to be saying, ‘This is going to be the right way to tell the story,’ instead of telling trans reporters or subjects, ‘Sorry, that’s not a possibility here.’”

False balance and false equivalencies are areas in which trans reporters like Sosin have pushed back. While some coverage of the North Carolina bill to restrict restroom access for transgender people gave credence to the right-wing claim that cisgender women had reason to be concerned about sexually predatory men coming into women’s rooms if trans women were allowed to use women’s restrooms, Sosin’s coverage didn’t engage with this mythology, which has no basis in fact. While the pro-Proposition 1 arguments—for example, a canvasser who was quoted asking a voter, “Do you want men in your little girl’s bathrooms in elementary schools?”—were mentioned in the coverage of the upcoming referendum in Alaska, the focus was on the community organizing effort to defeat it.

The Anchorage reporting Sosin produced with Lang shows how a trans journalist can see the importance of coverage a cisgender journalist might not see at all. Into was almost the only national outlet to do in-depth coverage of Proposition 1, which ultimately didn’t pass.

Trans writers have been outspoken in favor of hiring trans people to cover LGBTQ issues and have a growing collective voice in critiquing inaccurate and insensitive coverage

Both Sosin and Bendix were laid off from Into when Grindr shuttered the publication in late 2018. Yet, Sosin says, working for a news outlet that actively valued their trans identity made them want to stick with journalism. They are now a freelancer focused on the LGBTQ beat.

When Meredith Talusan became a writer in 2014, she also became a “trans writer.” At the time, it wasn’t really a choice. She is a transfeminine person who was good at writing about gender issues and, like a lot of writers from marginalized backgrounds who come into journalism through the chaotic freelance market, Talusan started out writing personal essays and hot takes. She freelanced for a couple of years while she was in grad school for literature. An editor friend of hers encouraged her, noting that there weren’t enough trans writers in national media.

But she was cautious. She had been living as a woman for a long time, but wasn’t out as trans in every context. Being an out trans writer required playing the role of translator, explaining the subtleties of trans experiences to an often-unfamiliar and sometimes hostile audience. “Do I really want to deal with this in my life? Do I really want to be openly trans in the world?” she asked herself.

Ultimately, she decided it was worth it and became BuzzFeed’s first openly trans staff writer in 2015, on the LGBTQ beat. She subsequently became the executive editor of them, and she is now working on a memoir about her early life as an albino Filipina trans woman.

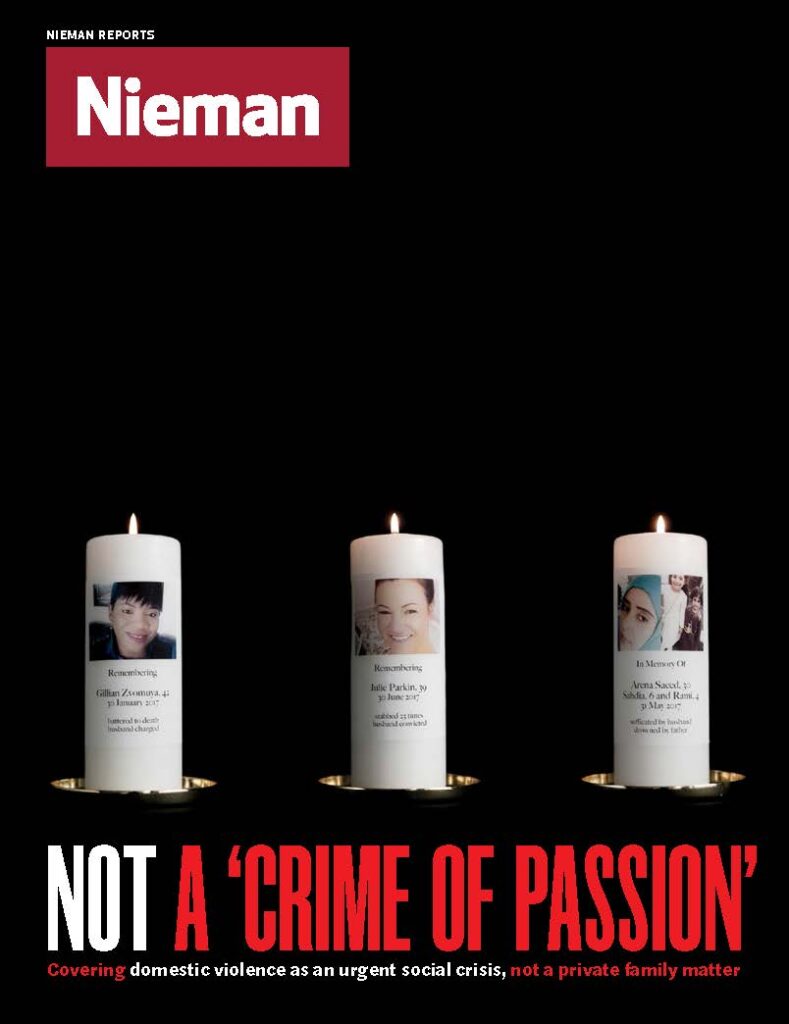

Talusan has never had a trans editor but, like Sosin, she’s had good experiences with some cisgender editors. She recalls working on a major investigation of murders of trans people—with editor Gabriel Arana at Mic—which attempted to count how many trans people had been murdered in the U.S. since 2010, a number not otherwise tracked. “From 2010 to 2016, at least 111 transgender and gender-nonconforming Americans were murdered because of their gender identity; 72 percent of them were black trans women and gender-nonconforming femmes, who identify as neither male nor female but present as feminine,” Talusan wrote. The chance of being murdered for a young black trans woman was 1 in 2,600, while among the general population it was 1 in 19,000.

“I feel like I had an unusual amount of latitude with that feature,” Talusan says, “because Gabe and I had a strong working relationship, but also being a racial minority himself and working on diversity issues extensively, he understood the importance of the piece being simultaneously for trans people and a broader audience.”

Arana had prior experience covering trans issues, and he was aware of the power dynamics that can arise between editors and reporters writing about marginalized communities of which they are a part. “I’ve edited other LGBTQ writers, where I’ll raise an objection that a reader might have and say that we need more context, and someone will think that I’m questioning the validity of their experience,” Arana says, adding that walking this line requires trust and humility on the part of the editor. “Some editors see themselves as hard-asses and want to come in and radically revise the text, but when you’re dealing with more sensitive topics that are close to somebody’s heart, you have to be more sensitive.”

Both Talusan and Arana acknowledge the tensions that can arise when trans journalists are asked to explain concepts that may be familiar in trans communities but unfamiliar to a majority-cisgender audience. Lots of trans articles end up doubling as trans 101s, providing explanations of issues like pronouns and assigned sex, or explaining terms like cisgender. In Talusan’s Mic feature on trans murders, not a lot of time is spent explaining what a transgender woman is. But there are moments of explanation and education, such as the definition of “gender-nonconforming femmes.”

“The public in general is ignorant about transgender issues,” says Arana. “So you want to give good-faith readers a lifeline to help them understand, in this case, the epidemic of violence against transgender people.”

Talusan and Arana show that editors are well-served by listening carefully to trans people’s perspectives while also having the confidence to push for clarity. There is almost inevitably going to be some tension between writing for a trans audience and writing for a general audience. Cisgender editors should start by listening, and trusting their trans reporters.

Trusting trans reporters is a particularly sensitive issue given the public rhetoric on trans people. Talusan and other trans journalists and editors I interviewed talk about the frustrating realities of false balance in coverage of trans issues. Trans people’s personal stories are often “balanced” with the opinions of those who question our fundamental rights to health care, safety, and employment, or depict us as dishonest or untrustworthy. And while trans people are often expected to disclose and probe our own “bias” as trans journalists, cisgender journalists covering trans people are rarely asked to do the same probing of their own gender experience and how it might shape their work. To counter this, activists have advocated for media outlets to hire trans people to cover trans stories, as a way to proactively address the structural inequity that still allows cis people to be the most well-known journalistic voices on trans issues.

Of course, there are plenty of trans journalists who don’t want a trans or LGBTQ beat. I worked for five years as a journalist in mainstream public radio, in newsrooms where I was always the only out transgender person. I rarely covered trans topics, but I always had to navigate my identity, particularly when I was starting a job.

In my very first journalism position, at WBEZ in Chicago in 2012, I was pleasantly surprised by how little fanfare my gender created. I was nervous about everything: what to wear, how much space to take up, what to do with superiors or peers who called me the wrong pronouns, what bathroom to use.

While trans people are often expected to disclose and probe our own “bias,” cisgender journalists covering trans people are rarely asked to do the same

I located a gender-neutral bathroom, and my supervisor found out what pronouns I used and told others. The only time in the onboarding process when my trans identity stood out was a conversation with the managing editor about conflicts of interest. I had been a sex educator and given trans ally workshops for many years and, initially, the managing editor suggested I avoid covering queer and trans issues. My supervisor pushed back, noting that my work had been educational in nature, not advocating for any specific policy. I was allowed to cover trans issues, although I ultimately pursued a beat where I was unlikely to come across perceived conflicts of interest.

Later, I moved to a small-town newsroom in Ohio, WYSO, where I received a warm welcome combined with some awkward communication about employer health insurance. As with many trans people, my official legal documents didn’t—and don’t—align with the name I use and didn’t reflect my current gender identity. For a variety of reasons, it makes sense for me to continue to receive health care as “female.” Until a nonbinary option exists vis-à-vis health insurance, many trans and non-binary people find ourselves in difficult positions in this regard. The best thing an employer can do is tread lightly, respect confidentiality, and recognize that the problem is not the trans person, but the inflexible system in which we’re working. If you’re confused about what is respectful, ask rather than guess. My manager at WYSO did just that; health care questions were quickly resolved, and we moved on.

The more difficult thing about being a trans reporter in a small town was my level of visibility. Even though I rarely covered LGBTQ stories, I was on the radio nearly every day, many people knew I was trans and, for many people, I was the only trans person they knew—or, at least, that’s what they thought. I was often asked for information on trans issues, which was not a role I relished.

I did not want to be tokenized while I was just trying to do my job as a journalist. And honestly, I didn’t want other people to know how traumatized and angry I was over a decade into my experience as an out trans and non-binary person. I was called the wrong pronouns, was scared or unable to use bathrooms in many reporting situations, and never had an active ally or support while navigating that at work. My composed outer shell was important to me and helped me do a complicated job. Why should I be asked to be vulnerable in ways that my colleagues rarely were?

Requests for education and information mostly came from outside my workplace and had little to do with my employers themselves. Still, the pressure to be an educational resource, representing your whole diverse community, remains near-constant for trans people, even those of us who don’t open ourselves up to it. I tend to think this dynamic is no one’s fault in particular, but our cisgender colleagues can be sensitive to it by not asking trans folks to speak for “the trans community” or educate them, knowing that many of us will have been asked that too many times to count.

Another aspect of trans sensitivity in newsrooms close to my heart relates to the longstanding debate over objectivity and whether journalists can, or should, strive to be objective about their subject matter. Transgender experience has a complex relationship to “objective” science, as modern science has long claimed that there are “objectively” two biological sexes, even as trans and intersex bodies and experiences predate Western medical understandings of biological binary sex. The Vatican in June released a document in which it rejected the notion that individuals can choose their gender. Psychologists and medical doctors remain gatekeepers over who is recognized as trans. And many trans people encounter conflict, violence, and abuse as a result of others believing we are “objectively” the sex we were assigned at birth.

Thus, many trans journalists are well situated to question the premise that anyone can look objectively at gender or sexuality—although, of course, some trans people believe in the concept of objective news reporting. Many black and indigenous journalists have advanced similar critiques of objectivity for decades, pointing out that it tends to assume the neutrality of a white, male perspective. In my own experience, I have had to be an activist and advocate for myself and my community in order to get into newsrooms at all; drawing a clear line between activism and journalism often appears to me a function of privilege.

Trans coverage, even employing outspoken trans journalists at all, remains highly politicized. My experience bears mentioning. In early 2017, I was fired from a national reporting job at “Marketplace,” a show produced by American Public Media, after I publicly critiqued the limitations of objective news reporting in the Trump era and called for journalists to stand up against white supremacy, xenophobia, and transphobia. I went on to research the history of objectivity in journalism and the impact of marginalized journalists on the profession. My book, “The View from Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity,” published by the University of Chicago Press, comes out in October.

I have been out since I was a teenager, so I never had to go through the experience of transitioning or coming out while in the workplace. But technology reporter Ina Fried did. She transitioned at work in 2003 while a writer at CNET, a tech news site, a few years after she came out in her private life. “I didn’t think I would get fired,” she says, “but I was worried I would have a hard time doing my job. And there weren’t a lot of examples, particularly at mainstream newsrooms, of reporters transitioning.”

Because she had a developed beat covering technology in the Bay Area, she had to contact hundreds of sources about her change of pronouns and presentation in addition to coming out to her colleagues. This process tends to be exhausting, overwhelming, and rife with oversharing from others about how they feel about your transition. A lot of people change jobs, or even move, to attempt a sort of fresh start. Fried loved where she was and what she did but says it was a lot to go through: “It’s not easy to transition in place, if you will. It’s hard for coworkers, or sources, who have only known you as one gender.”

Trans coverage, even employing outspoken trans journalists at all, remains highly politicized

She was also distracted at first by questions about whether colleagues and sources were seeing her as a woman. “My sense of self would rise and fall with somebody using the right pronoun or not.” But ultimately, the payoff was high for both her and her employers. Now a technology reporter at Axios, she has a track record of bringing fresh ideas for LGBTQ technology stories into her work, such as a 2015 piece about a tech employee who came out to millions of people via text message.

Fried thinks the last couple of years have been hard even for the most apolitical trans journalists. “Being trans, especially at this moment, there’s an element of it that’s just political by its nature,” she says. “It is challenging to live at a time where my identity and the identity of my community are under near constant attack. It makes it challenging to be in a role that I believe strongly in, which is a journalist writing without bias.”

While she says she hasn’t become an activist, she says the Trump era has put a strain on her ability to stand on the sidelines, both as a trans woman and as a Jewish person. When she talks about these issues within her newsroom, she says, colleagues are receptive and thoughtful, and younger journalists are grateful for the example she sets by speaking frankly.

In my experience, trans people aren’t inherently more knowledgeable than cis people about gender and its discontents, but chances are high that we have thought about these issues a lot more than the average cis person. Still, we all have a lot to learn, and trans and queer terminology and discourse are constantly being refreshed and updated by younger generations. Just as trans journalists are having an effect on which stories get covered and how, trans editors and leaders are important to building a media landscape that does a better job representing marginalized people and communities.

Almost every one of the eight people I interviewed for this story said they’d never had a trans editor. I have been one and had one once, Meredith Talusan, when she was at them. This reflects the structural barriers to entry for trans people such as legalized discrimination and the emotional and economic costs of transition.

Molly Woodstock, a non-binary, indigenous journalist based in Portland, Oregon, responded to these barriers by starting their own show. When they’re not working as an editor at SagaCity Media, which owns Portland Monthly, Seattle Met, and other publications, Woodstock hosts and produces a podcast about gender called “Gender Reveal.” They air weekly interviews with queer and trans people; their current season focuses heavily on interviews with journalists. “My whole life is about being trans and being queer and being indigenous, and other forms of intersectionality,” Woodstock says. “I started the podcast to create a space where trans and nonbinary people could have those conversations.”

“Gender Reveal” can also be the educational resource that trans journalists on the job don’t want to be. “‘Gender Reveal’ is a space where we do ask the intrusive personal questions in a way that’s hopefully respectful, and people are going into it consenting,” Woodstock says.

On one recent episode, Woodstock talked with trans reporter Katelyn Burns about Burns’ experience covering Congress. Burns and Woodstock also critique a recent New York Times story about chest binders, written by a cis reporter, for dabbling in false equivalencies by quoting anti-trans extremists. This kind of self-made trans media is part of a long tradition of “for us, by us” media by marginalized communities that doesn’t take the place of mainstream journalism, but creates space to surpass as well as criticize it.

Willis is perhaps the most high profile trans person in an editorial leadership position. In December, Willis became the first black trans woman executive editor at Out.

Her path to the job involved advocacy. She studied journalism in college and put in a year as a reporter, in the closet, at a small-town Georgia paper. “Being marginalized and feeling like I was so silent for so many years about my own trans identity made the perfect conditions to want to be a storyteller to liberate other people,” she says.

But after she came out as trans, Willis became frustrated with the journalism industry, its value of objectivity, and the constant transphobia and microaggressions she experienced in that world. She shifted her focus to activism, taking a job at the Transgender Law Center in communications. “I really value that experience because it gave me more of an authentic opening to the actual needs and desires of the trans community, stripped away from this media narrative that’s focused on this post-Caitlyn Jenner world where being trans is either glitzy and glamorous or it is tragic and all about death and the murders of black trans women. It gave me a more holistic idea of what the rest of my people were going through.”

Willis has always struggled with the notion of “objectivity,” which is why a job for an explicitly LGBTQ outlet made sense for her. “Stripping yourself of your identity, not having a lens or a perspective … that’s a very privileged approach,” she says. “It’s very easy to be like, ‘You shouldn’t have an agenda,’ when the agenda is a white heterosexual Christian man’s agenda, so that doesn’t seem like an agenda to those people.”

Out caters to a niche audience, but it’s also trying to change its niche. In the past the outlet focused predominantly on white gay men but has recently hired a new editorial staff that leans heavily toward trans, women, and people of color. Hiring Willis sent a message about that new focus, and her new team will more closely reflect the members of the LGBTQ community most in need of better, more varied representation.

“The truth is, no one writes for everyone, even in journalism,” Willis says. “I hope that as our community continues to grow and our voice continues to grow there will be more opportunities for trans people of all different backgrounds to make their experiences known. We don’t have a monolithic experience. We come from every corner of society that is imaginable and that’s a beautiful thing. And we need to hear all of those stories.”

An earlier version of this story used the incorrect pronoun in one place to refer to Kate Sosin.