Published by Beacon Press on January 8, An Xiao Mina’s “Memes to Movements: How the World's Most Viral Media Is Changing Social Protest and Power” explores internet memes as agents of global politics, protest, propaganda, and pop culture with transformative powers—for better and for worse, both on- and offline.

An edited excerpt:

This story about East Africa starts with a text message in Western Europe. Years before much of the financial and social turmoil that struck the European Union in the late 2010s, there was the 2012 Spanish bank bailout. Struggling with the need for additional financial support from the EU, Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy sent a reassuring text message to his finance minister:

Aguanta, somos la cuarta potencia de Europa, Espana no es Uganda.

Resist, we are the fourth power in Europe. Spain is not Uganda.

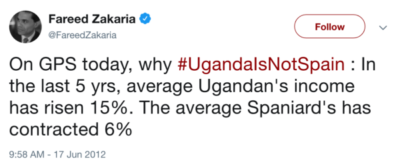

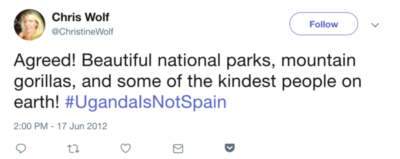

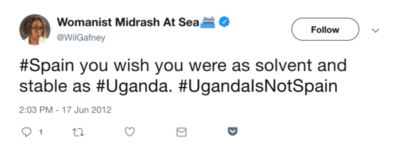

The words were picked up in international media, making a few headlines. Rajoy seemed to be suggesting that although Spain might be struggling, at least it’s not a poor country in Africa. In another era the response might have come and gone quickly, a turn of phrase with a flash of interest before being quickly forgotten. But the response on social media was speedy, and it came from what at the time seemed an unlikely source: Ugandans themselves. Posting a video on YouTube, Ugandan journalist Rosebell Kagumire called out the remarks and started a hashtag trend on Twitter that would echo throughout social media: #UgandaIsNotSpain.

The brash, quirky humor caught many by surprise, and international media outlets quickly picked up on the response. After covering the many biting responses, BBC News compared the economies of the two countries, and Al Jazeera pointed out the absurdity of the comparison, noting the rapid economic growth Uganda had experienced. Foreign Policy hosted an opinion piece from Ugandan journalist Jackee Batanda:

When the world looks at emerging markets, it is the countries like Uganda that offer hope for the future of growth. It is therefore important to correct the perception that Uganda is a lost cause. That’s a long way from the truth. Uganda is a resource-rich country with a vibrant culture.

The hashtag provoked a round of public soul-searching on the part of both Spanish and Ugandan media. Spaniards expressed dismay about their leader, while others took pride in their country’s health-care provisions and overall GDP while pointing out the country still had many systemic problems.

Related Reading

Authenticity and the Journalism of Networks

by An Xiao Mina

These sorts of conversations are typical now when a social media outburst pokes at people in power. But the most remarkable aspect of this story is that, for a rare moment, people from a historically overlooked nation (how many people outside East Africa can point out Uganda on a map?) were able to drive the conversation on international media.

What Ugandans on YouTube, Twitter, and in the media managed to achieve, in a matter of days, was attention. Kagumire, a trained journalist with an under standing of social media dynamics, clearly recognized a moment of opportunity, and she sparked a hashtag that remixed the prime minister’s reported choice of words. This hashtag, in turn, drove attention to the clever tweets that people posted, which international media picked up on, thus sparking another conversation. The reason it worked relies on a number of factors. The world was already watching the issue and discussing Rajoy’s poor choice of words. Ugandans were then able to leverage the existing attention and judo it to a conversation about misguided assumptions about both countries.

What also mattered here was technological access. Compare this cross-language, cross-continental back and forth on Twitter to how things might have unfolded before social media. Historically, news outlets have relied on letters to the editor and phone calls to understand reader responses. By the time an international newspaper reached Uganda, someone in the country, upset by how his country was portrayed in the news, could write a letter or make a phone call. But delivery could take weeks-and by that time the news cycle would almost certainly have moved on. A phone call might have worked, until you considered the cost: a few cents per minute for one person to call in could easily add up and be prohibitively expensive. Further, one person can be ignored. Without social media, few ways existed for a significant number of people to show their disagreement with Rajoy’s framing of Uganda.

...

In the 1980s, when Mariano Rajoy began his political career, Uganda was facing more difficult times. After Yoweri Museveni took power as president of the country, Joseph Kony, a military leader from northern Uganda, led the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), known for its cultlike culture and ruthlessness, to challenge Museveni’s rule. Then Kony began the resistance, the internet was little known, but he, too, would become a meme of sorts.

Just months before #UgandaisNotSpain took off, another hashtag about Uganda had taken hold of the world, driving attention to the country and, more specifically, to the LRA. In March 2012, Invisible Children, an NGO (nongovernmental organization) and advocacy organization based in California, released a video about Joseph Kony. “For 26 years, Kony has been kidnapping children into his rebel group, the LRA, turning the girls into sex slaves and the boys into child soldiers,” noted Invisible Children founder Jason Russell in KONY 2012, a thirty-minute video that quickly went viral. In the film, Russell speaks to his son. “He makes them mutilate people’s faces, and he forces them to kill their own parents.” The video was combined with a digital outreach campaign on multiple social media channels, all organized using hashtags such as #StopKony and #Kony2012.

The campaign took off. Millions of social media posts later, Invisible Children was able to drive a stunning range of international attention to their cause, compelling the United States, the African Union, and the United Nations to pledge troops and resources to hunt down and capture Joseph Kony and stop the LRA from committing any further abuses. The goal of #StopKony didn’t quite come to fruition—Kony himself had long since left Uganda and relocated to the Central African Republic, a few hundred miles northwest of Uganda. But the campaign served as a model for many Western organizations as they sought to drum up attention and support for often-overlooked issues.

Occurring in 2012 about the same country, both #StopKony and #Ugandais NotSpain serve as a useful comparison for how something as simple as a hashtag can drive a conversation. Through sheer scale of users, hashtag trends can involve many more people, who gather online in a form of digital public assembly, than traditional physical organizing. In addition, the joking and one-upmanship of these trends, as people compete to make the best quip or joke, serves as a useful way to drive attention. This is not simply because of the number of posts. Rather, the variety of posts and the range of remixes serve as a sort of Darwinism of attention, where only the best and fittest posts float to the top, thanks to multiple shares decided by multiple people. University of Michigan communications professor Amanda D. Lotz has noted that intentional overproduction is a key strategy in traditional media, which deliberately create multiple shows, commercials, songs, and other media, because they never know which one will quite take off.

Hashtag culture functions in a similar way, but the overproduction is created by many people, riffing off of each other. Algorithms like Twitter Trending catch them and highlight them in a section on the site that is visible to many, which in turn drives more attention. People outside the group might see it trending on Twitter and start asking, “What’s going on here?” And soon local media and the international media catch on, followed by an international conversation about the issue.

Excerpted from "Memes To Movements: How The World’s Most Viral Media is Changing Social Protest and Power" by An Xiao Mina (Beacon Press, 2019). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.