Cartoon by Klaus Stuttman, Berlin, Germany. Reprinted by permission of Cartoonists & Writers Syndicate/ cartoonweb.com.

The cover page of Der Spiegel displayed the globe as a broken egg. “Pax Americana—The new world order,” read this influential magazine’s headline days after the fighting in Iraq ended. On the inside pages of this German publication, editors made the point that the majority of the German public and most German media share: “The allies have won the war against Saddam, but the fight over the post-war future of the country is far from over.”

Skepticism and criticism about the military campaign in Iraq and its goals are widespread in the German media, although most publications did not hold an uncritical attitude towards the Arab world, in general, or sympathy towards Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, in particular. In many newspaper stories the crimes and oppression of Saddam and his inner circle were described in vivid ways—the human rights violations, the torture and assassination of political opponents, the wars against Iran and Kuwait, and the gas attacks against Iraqi Kurds and Iranian soldiers. Other news reports focused on the backwardness of Arab societies, the growing anti-western sentiments, and the influence of fundamentalist Islamic movements.

In the German media, most editorial writers and news reporters have not been convinced that a connection between September 11th and Baghdad exists or that Iraq, after 12 years of United Nations sanctions, still posed a threat to its neighbors, to the United States, or even to the world. The performance of the United States in the U.N. Security Council was viewed by most in the media as reckless propaganda of the superpower using false or even fake information to push its war agenda. Widely covered by German news organizations, too, were also the failed American attempts to blackmail weaker U.N. Security Council members to secure their votes for a second resolution. Even the U.S. goal of democratizing Iraq (and potentially the entire Middle East) is regarded as pure rhetoric or seen as hopelessly idealistic and naive.

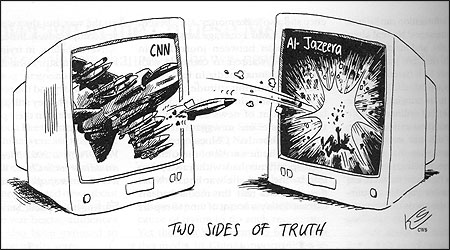

In its daily coverage, the German media’s focus was very much on the horrors of war and of the potential casualties of the air bombardments, the propaganda being put forth by both sides, and on the worldwide protests of the peace movement. Reporting also dealt with the criticism made by various church leaders against President Bush’s use of religious language to justify the military engagement and the fierce diplomatic tensions between the U.S. and British allies on one side and Russia, China, France and Germany on the other.

Several papers printed a notice each day for their readers to inform them about the specific problems and limits of war coverage when the military controls the news and when, as was written in Berlin’s Tagesspiegel, “the number of official lies increases drastically—on all sides.” There is no “clean” war; there are no “surgical” air strikes. “Shock and awe” means death and horror, and that was the message the media tried to forward to their readers. Many thousands of people were killed. The nation’s infrastructure was in ruins, with Iraq bombed back to the oil lamp economy of the 19th century, as one paper wrote.

War is always a defeat for mankind, Pope John Paul II said, and this message was the hidden red thread of considerable parts of the German media coverage. Stern Magazine used the line, “God’s Warriors and their Victims,” as the title for a series of three photos, each of which was at least a full page in size. In the first one was a blood-covered dead young mother together with her dead child, with the pacifier still in the child’s mouth. On its opposite page, an American soldier had his combat pack on which he had written the Biblical words, “I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” The following double page then showed a young Iraqi mother seeking shelter in a ditch together with her two kids. She had pure horror in her eyes; this extraordinary photograph was used as a front-page image by other German print media as well.

The Iraq war was the first live war in history. It was probably also the most widely reported and taped military fighting ever. The whole world was watching as dozens of “embedded journalists” talked through their videophones. But what did most of these “info-combatants” really produce?

“News fog,” judged the national daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung when it printed a detailed documentary of war propaganda of both sides including, among others, a list of the numerous alleged discoveries of chemical weapons by the American army on their way to Baghdad.

However, in the eyes of German media, no other event did more damage to the American case than its failure to guard hospitals, ministries and the national museum and library in Baghdad. This failure to protect civil order and save the collective memory and cultural roots of the Iraqi people led to critical stories and headlines. “The worst invasion of Baghdad since the Mongols” read the headline in the national paper Süddeutsche Zeitung, published in Munich, after the vandalism, looting and arson finally ceased. Several other papers called the damage done within those 48 hours a “Cultural Super-GAU.” (In German, GAU is used to categorize severe nuclear power accidents; in English, it means “worst imaginable accident.”)

These events were widely viewed as a devastating omen for the future of Iraq and as inexcusable proof of American ignorance and incompetence, especially when it was reported that the American military command only protected the oil ministry. When the Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, later compared the looting of the unparalleled treasures of Mesopotamia with the behavior of football rowdies, one newspaper even speculated that a country with some 300 years of history might be unable to grasp the meaning of 5,000 years of history. Another paper relied on irony to make its point by inserting in its coverage of the cultural losses a quote from President Bush’s speech to the Iraqi people, which aired the same day the looting started: “The nightmare that Saddam Hussein has brought to your nation will soon be over. You are a good and gifted people—the heirs of a great civilization that contributes to all humanity. You deserve to live as free people.”

Such heavenly rhetoric leaves many German journalists with doubts and mistrust. To destroy the dictatorship in a relatively small country by military force is an easy thing compared with the complex task of developing improved and stable civil order. The military battle took three weeks; the battle for Iraq’s future will need many years. And it might well end in another nightmare for the people of that country.

Martin Gehlen, a 1992 Nieman Fellow, is a political writer at Der Tagesspiegel in Berlin.