The author conducts an Internet live chat with George W. Bush. Photo courtesy of America Online.

1992

Covering a campaign as a TV reporter is like being sequestered in a biosphere. After a while, you can’t remember how to relate to the outside world. In 1992, I kissed my family goodbye and trailed George Bush (the dad) as an ABC News correspondent for nine months. The hardest part was trying to figure out what average people would want or need to learn each day from the campaign, those people who went about their daily lives outside of this voter-free bubble in which we traveled. Bear in mind that, for “World News Tonight” or “Good Morning America,” I usually had one minute and 15 seconds to sum up the day. That’s five sentences. (I’d be done right now if this were my TV report.)

Always in pursuit of a new angle, our video Cliffs Notes often focused on symbolism or tactics of the campaign that wouldn’t help the less than hardcore voter make a decision, unless the viewer watched our pieces faithfully. And we didn’t kid ourselves that they did. Our public was the press plane. We held court in the sky as we dined on filet mignon and chased Air Force One to the next battle. Once, after our filing deadline, we had an airplane pillow fight. From press plane to bus to staged campaign event to hotel, we had no contact with real voters. The only contact we had was with “supporters” who would poke us with the blunt end of those American flags they hand out at rallies to drive home the President’s campaign slogan, “Annoy the Media, Re-Elect George Bush.”

I feel like I made some important contributions to TV journalism during my 13 years on the road. None of them, however, came from my year in that biosphere.

1996

By 1996, the fine dining was gone, along with the driver to get me to my “Good Morning America” live shots. When Ted Koppel left the GOP convention in disgust that summer, saying that there was no story and the parties were just trying to manipulate the media, I was having an epiphany of the opposite sort.

Now heading up political coverage for America Online, I was hunched over my laptop in the nosebleed seats in the GOP convention hall, responding to questions from voters in real-time. We ran live “help” chat rooms to decipher the speeches, where experts explained what was really going on, their comments driven by the live questions from voters.

While Koppel worried about feeling manipulated, we could put voters in the control room and let them shape their own experiences based on their own definitions of news. At AOL, for example, we invited subscribers to rate the speeches (Colin Powell beat Elizabeth Dole). We independently solicited delegates from the Democratic, Republican and Libertarian conventions to write daily diaries and managed to cut through the “message of the day.” At the GOP convention, the Republican Party downplayed the platform that got approved, in part because of the squishy compromise language on abortion. The GOP Web site buried the platform. On our site, when members kept asking for it, we linked directly to it from our front politics page.

While our audience was still very small and not yet mainstream in 1996, I realized that what I had been carefully cramming into my TV spots was not what voters were looking for. The ratings or “page views” in the Politics section of AOL told us that wired voters, at least, wanted facts. Not inside baseball. Not spin. Not candidate speeches. Not candidate ads. Not the latest polls. Not even to have issues carefully explained. Bare-bone information, quickly and conveniently.

2000

Just before this year’s New Hampshire primary, there was a farewell party for veteran journalist Jack Germond at the famous watering hole, the Wayfarer Bar, south of Manchester. He said on CNN recently that campaign reporting and being a boy on the bus is no fun anymore, what with everyone typing away on their laptops all day long and nonstop deadlines. He said this would be his last campaign.

Indeed, laptops and technology have made the political campaign a wholly different experience. The press marveled at the Internet voting experiment in Arizona’s Democratic primary, and John McCain showed how effectively a Web site could turn his “big mo” after New Hampshire and Michigan into six million dollars in cyberspace donations, circumventing the GOP party machine that had already elected George W. Bush.

What has also been interesting this year is the number of dot.com startups that are flooding into politics, backed by lots of venture capital—Vote.com, Voter.com, GoVote.com, Election.com, Grassroots.com, and Politics.com. Most of the editors of these sites would argue they have a journalistic mission, at least in part, but what they really want to do is reinvent the voters’ relationship with politics. To the extent that these sites have more money to spend this year than the news sites they compete with such as washingtonpost.com and CNN.com, political journalism could look very different by 2004.

The Dot.com Era of Political Reporting

At AOL, we are a hybrid operation. We have an online newsroom that aggregates traditional news sources into packages for our 22 million members. And we have people like myself who are building out “vertical markets” such as politics and government.

My role is to develop interactive tools, ways for citizens to interact with information or government officials and agencies in a convenient fashion. Some examples include zip code look-up directories to help voters figure out who is running for local offices, a weekly “people’s press conference” with the White House (“Ask the White House”), and even online government services such as driver’s license renewal or product recall information.

I find that I feel compelled to deliver more of a public service than I would have thought appropriate as a network TV correspondent. I offer two examples. One is BeAVoter.org, an online voter registration drive that AOL has developed this year with partners MCIWorld.com and AARP. While some newsrooms might argue that this crosses the line, because encouraging registration is stepping into the process, I felt it was core to our convenience mission to make voting easier and more likely.

AOL’s most heavily trafficked voter service this year is President Match. (AOL Keyword: President Match, or www.presidentmatch.com.) A joint project with CBS News, it is an interactive quiz that helps users to match their own views with those of the candidates. People find it interesting and useful because it strips away their preconceived notions about who is most electable or charismatic and ranks the candidates purely on the issues.

The Internet will be even more useful in helping voters get similar information at the state and local level. As a voter, I always feel a little ashamed checking boxes for local candidates when I know nothing about them. The way most news sites are set up now, this fall you’ll be able to type in your zip code and in many cases be able to get information about candidates running even at your local level. Since most local political jurisdictions don’t map easily to zip codes, the real promise of convenient, consistent access to information that helps you choose among local candidates may not be fully realized until the next cycle.

The other big difference in my journalistic life now is that I am not a celebrity, or “talent,” as TV reporters are called by producers and cameramen. I was never a star, but I got recognized in the grocery store, and my grandmother would gather all her pals around the retirement home to watch my pieces on the evening news.

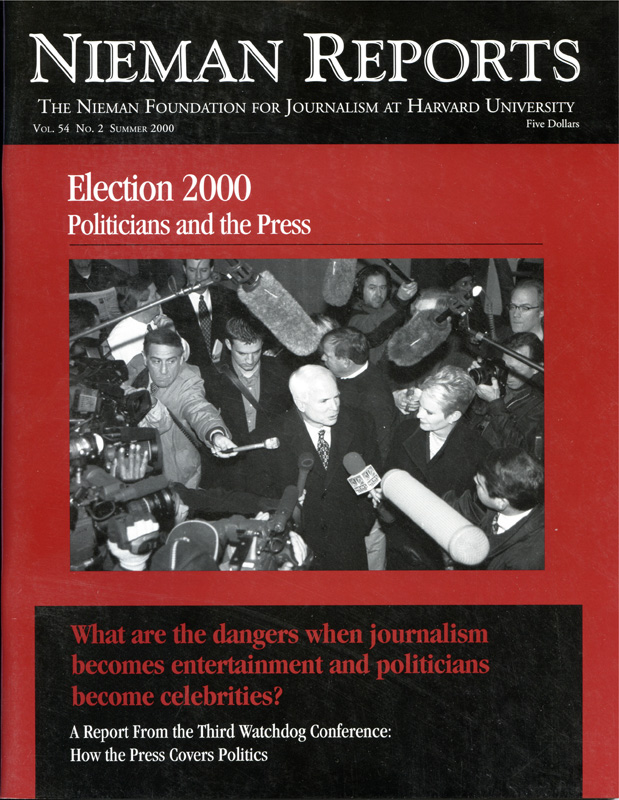

During the course of this campaign, we have conducted live interviews with all the major presidential candidates, so even though I have moderated most of these events, I do it under an online alias, “AOLVotes.” My role is to screen questions from the public and choose which ones get asked to the candidate. I try to resist the urge to ask the incisive follow-up unless the candidate hasn’t answered the question.

It’s very humbling.

My husband asked me this morning, when filling out our tax return, “What should I put for you under Occupation? Are you still a journalist?”

I hesitated. “Not really.”

He pushed, “Well, what should I put?”

I don’t know. I ran into an old AOL friend who went to another Internet company. He said his new title there is VP of Information Architecture. That sounds pretty good.

Kathleen deLaski, a former ABC News political correspondent, is now overseeing America Online’s coverage of politics and government.