Kurt Vonnegut once compared the artist to the canary in the coal mine, a hypersensitive creature who alerts hardier life forms to toxic gases by kindly dropping dead. Given the steady demise of editorial cartoonists during the past several years, newspapers might begin to wonder about the quality of the air.

Cartoonists have been keeling over in startling numbers—down from almost 200 just 20 years ago to fewer than 90 today. The poisonous fumes laying us low are the byproduct of the corporate culture that has engulfed newspapering during the past two decades. It is a bottom-line cult of efficiency that threatens not just my own profession but the integrity of journalism and hence the unruly spirit of democracy.

That is old news, and we’ve all heard reasons for the disappearance of the editorial cartoon. Circulation is down and budgets are tight. Newsprint costs soar. Editors forced to cut budgets look around and find the expendable employee, or the person least like them: the guy or gal who just draws pictures. Newspapers have survived challenges for 200 years, from the rise of the telegraph to radio and television and now 24/7 cable news programming. That is because the newspaper’s indispensable function has been to shape its community’s very identity through the distinctive voices and personalities on its pages. (Could one imagine Chicago without Royko?) Cartoons are the most accessible window into the character of the paper and its town. Yet more and more publishers are convincing themselves that they don’t need a local pen or brush representing them on the editorial page. Instead of having an artist who will continue to shape and reflect the soul of their community, they get by cherry-picking canned (and cheap) cartoons from syndicates.

Cartoons and the Bottom Line

When I started drawing editorial cartoons in the 1970’s, the profit margins on which newspapers operated were 12 to 14 percent. Today, it’s upwards of 25 percent. Most businesses—even Halliburton and Enron—have been content with five percent. We are told that newspaper operating capital in the low-to-mid-20’s—which, by the way, is on a par with that of pharmaceutical companies—is necessary because so much is required for production. By defining solvency up, the newspaper industry has switched its priorities from the public trust to the wealth of an increasingly centralized community of shareholders.

The fate of the editorial cartoonists demonstrates how this not only disserves society but also undermines the future the bottom-line watchers are trying to safeguard. Newspapers are playing not to lose when they should be playing to win.

Consider how the managers are pursuing the central mandate of their business model: to constantly expand readership. Their position is: “How can we expand readership if we make people mad? Anything that makes people think risks offending them and loses readership.” That the editorial cartoonists’ very reason for being is to provoke helps explain why they are the first to go. (From the same impulse, the old traditions of flirting, horseplay, razzing, smoking and drinking, have been filtered from the newsroom by means of human resources reeducation camps.)

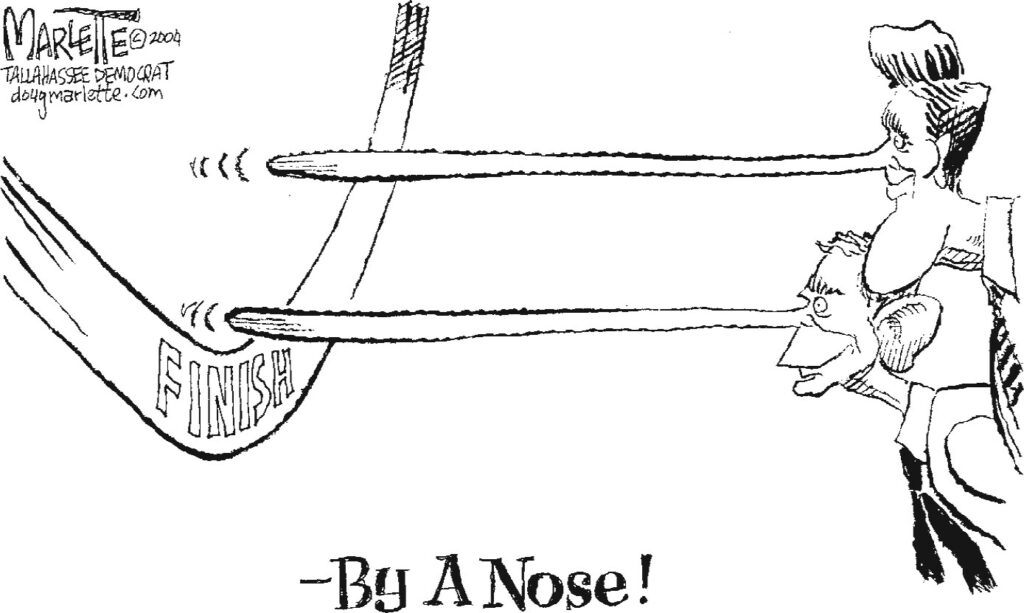

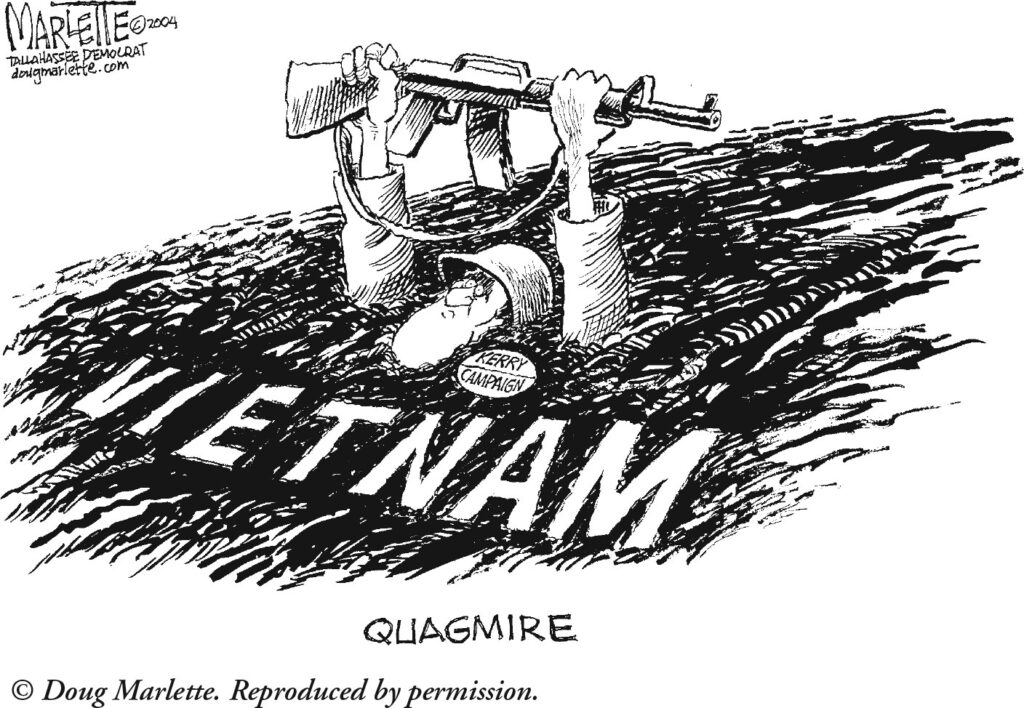

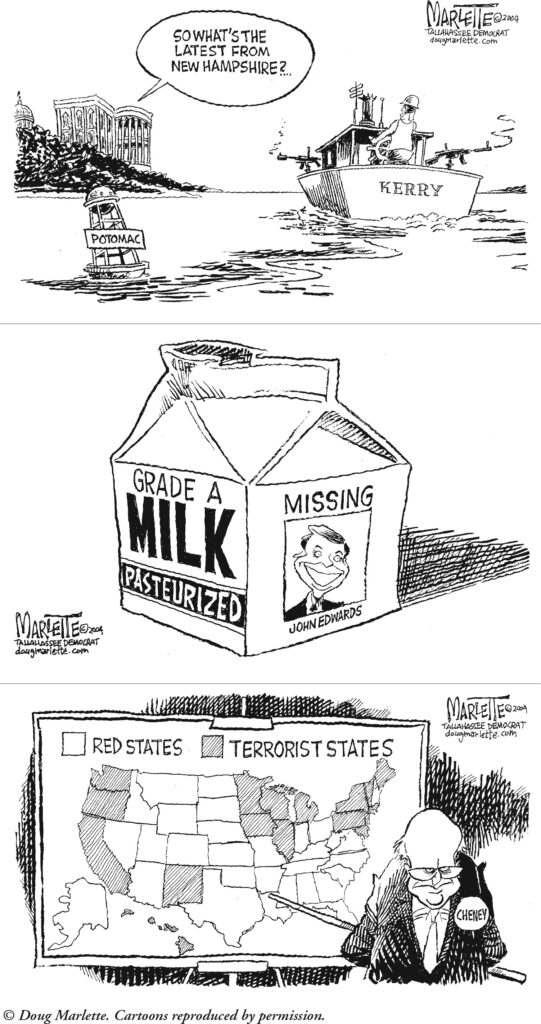

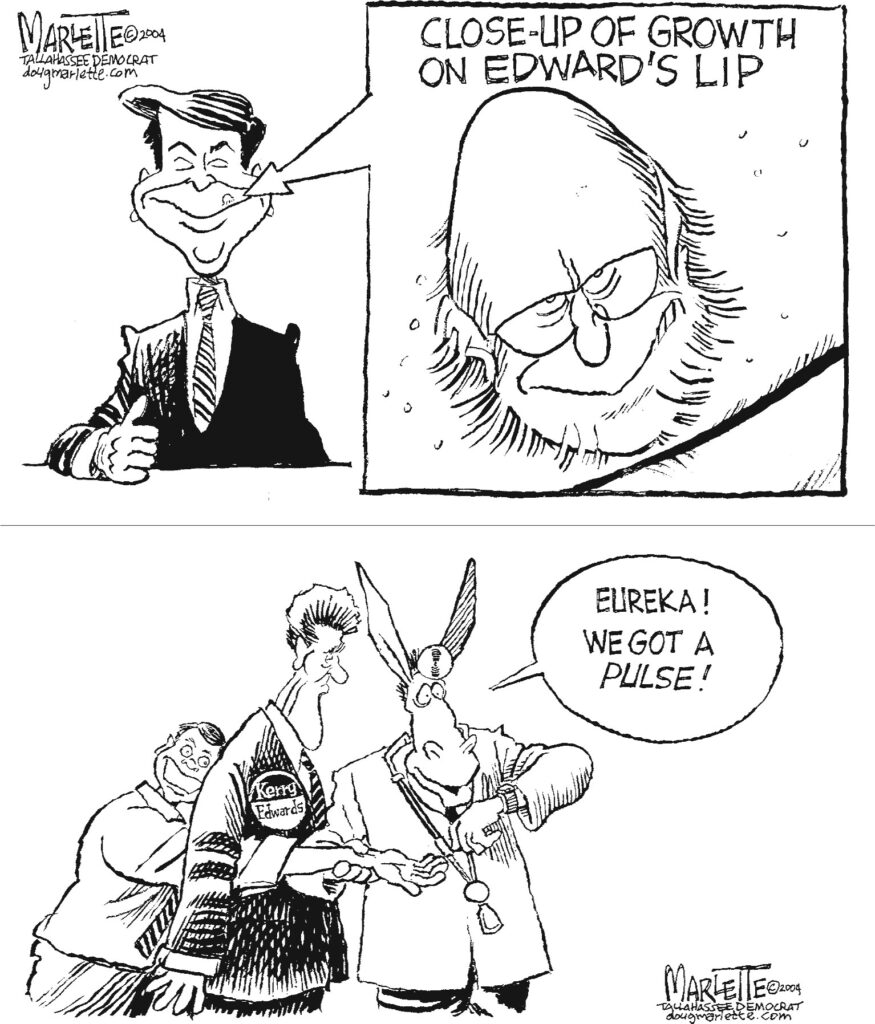

We cartoonists represent the untidy, untamable forces that corporate suits have always waged war on. We represent instinct, and we work in the most powerful, primitive and unsettling of vocabularies: images. Cave painting is not the same as hunting and gathering. And cartoonists reach the reading public in a place where words just cannot go.

Cartoons and the First Amendment

But what does the obsolescence of the editorial cartoonist have to do with the health of the democracy? Cartoons are the acid test of the First Amendment. They push the boundaries of free speech by the very qualities that have endangered them: Cartoons are hard to defend. They strain reason and logic. They can’t say “on the other hand.” And for as long as cartoons exist, Americans can be assured that we still have the right and privilege to express controversial opinions and offend powerful interests. The rise of a passive generation of parent-pleasing perfection monkeys makes preserving that prerogative seem more urgent than ever. “Minding” is an overrated virtue.

When we don’t exercise our freedom of expression in troublesome ways, we may atrophy our best impulses. The First Amendment, the miracle of our system, is not just a passive shield of protection. In order to maintain our true, nationally defining diversity of ideas, it obligates journalists to be bold, writers to be full-throated and uninhibited, and those blunt instruments of the free press, cartoonists like me, not to self-censor. In order not to lose it, we must use it, swaggering and unapologetic.

The insidious unconsciousness of self-censorship can be discerned in the quality of editorial cartoons today. Increasingly in my profession, career-ism seems to have replaced risk-taking. Proficiency stands in for talent. Too many cartoons look like art by committee. Emotional distancing has replaced the raw torque of yesterday’s best. Nobody feels; nobody cares. Nothing is brought up. And the controversies that are generated seem to result as much from the cartoon’s ineptness as its challenging content. Cartoonists have become victims of our cultural irony, delivering postmodern sneers rather than true passion or outrage. Where do they stand? Nobody ever wondered that about Herblock or Conrad.

When I got into the business, American political cartooning was in the midst of a renaissance. The sixties, in all their cultural and political agitation, had reinvigorated the form. A generation of artists raised on television and Mad magazine was further egged on and taunted by Australian Pat Oliphant’s juicy draftsmanship and incendiary content. Bob Dylan said recently that if he were starting out in today’s sterile pop music world, he wouldn’t go into music. I know just how he feels.

I ’m not sure that spirit can be revived, but I’d like to think so. My immodest proposal as I peek out of the slits in my bunker is that newspapers should save themselves by following not the business model but that model of survival, Mother Nature. A newspaper is an ecosystem, the health of which depends on the fitness of its symbiotic parts. When you eliminate one species, you threaten the vitality of the whole. If only cartoonists were valued as much as snail darters.

But we are only canaries.

Doug Marlette, a 1981 Nieman Fellow, is the editorial cartoonist for the Tallahassee (Florida) Democrat and the author of “The Bridge.” He won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning.