Water: A Life Force Harnessed as News

Water is the essence of life, and its cleanliness, availability, and our use and abuse of it are stories meriting reporters’ and editors’ attention. Yet as Stuart Leavenworth, who covered water issues for The Sacramento Bee and describes the wide array of issues he took on, reports: “To my chagrin, I had the beat largely to myself for four years. Across the country, papers have tackled problems of water pollution and degradation, but have overlooked fundamental issues of supply—and sustainability. This is curious.”

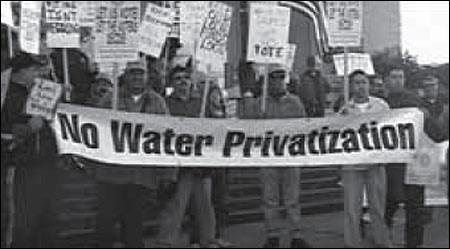

At the 2003 World Water Forum, Oscar Olivera, a Bolivian community leader, declares there is no consensus for water privatization. Photo courtesy of Snitow-Kaufman Productions.

Aqui, no hay acuerdo! “Here, there is no consensus,” declares Bolivian community leader Oscar Olivera near the end of our documentary “Thirst,” as he tears up the Final Report written by the bankers at the 2003 World Water Forum in Kyoto, Japan. His impassioned speech was a message to the gathered international financial and corporate elites that the corporate takeover of global public water supplies and services would not happen without a fight.

As documentary filmmakers, “No hay acuerdo!” could serve also as our mission statement. We see our work as disrupting the tendentious framing of major issues by elites and an often-unquestioning media. We try to provide an alternative framework that challenges the status quo and sparks a debate on contemporary social issues. In “Thirst” and our other documentary work we do this by following stories of conflict and offering multiple points of view to create openings for our audiences not only to see these issues differently, but also to see themselves as potential actors once the film is over.

We were motivated to make “Thirst” in order to chronicle what we see as the pitched and unbalanced battle between the public and private sectors in the United States. The one-hour film, which was aired nationally on the PBS series P.O.V. in 2004, sheds light on the largely behind the scenes efforts by multinational water companies to take over public water services and supplies. The privatization effort is part of a larger far-right political campaign to convince people that corporations can do virtually anything better, cheaper, faster and more efficiently than supposedly lazy, inflexible, corrupt and self-serving public agencies and employees. The corollary of this asserted ideological “consensus” is that private companies should take over most public services, including water.

The customary framing of privatization is in contrast to an alternative story—that corporations are engaged in the large-scale theft of public resources, victimizing families, communities and our environment for short-term profits at the expense of long-term security and sustainability. What we discovered in researching dozens of stories for “Thirst” is that when it comes to the basic life-giving resource of water, people will fight heroically to maintain local control and accountability. Powerful coalitions of labor and environmentalists seem to form spontaneously when the issue becomes whether water is defined as a human right or just as another commodity that is bought and sold on global markets.

In “Thirst,” the drama intensifies as viewers get to know and care about people on all sides of these debates, people whose words and experiences we filmed. We chose a character-based, story-driven format for the film rather than a fact-driven, talking-head structure, and we chose to avoid narration. Based on what they see and feel, viewers have to make the political connections and draw some conclusions for themselves. In other words, the viewer has to do some work. Ironically, by demanding this engagement, we also allow it, inviting viewers to commit themselves for a while to the characters on screen and the choices they make. Our aim is to dispel the apathetic ennui so often produced when the media spoon-feeds issues to what’s presumed to be an inert public.

Protesters gather in Stockton, California in February 2003 to oppose the mayor’s plan to privatize the city’s water system. Photo courtesy of Snitow-Kaufman Productions.

Core Themes Emerge

“Thirst” focuses attention primarily on the water privatization battle involving the people who live in Stockton, California, but interweaves that community’s struggle with stories of similar conflicts from the city of Cochabamba in Bolivia and rural Rajasthan in India. The stories are linked to one another through vociferous debates in Kyoto, Japan, where political leaders, bankers and corporate executives gathered to determine who will control the world’s freshwater supplies. At the Kyoto forum, a diverse group of grassroots “water warriors,” including Bolivia’s Olivera, defends water as a human right, not a commodity.

The stakes in these debates are very high. The ways in which water is owned and allocated reveals much about the structure of a society. Water conflicts expose the identity of rulers and the structure of their rule.

In Stockton, citizen opposition to water privatization forced city officials, billionaire developers, and corporate leaders out of the back rooms and into a public debate about a $600 million, 20- year contract—the largest water privatization deal ever in the West. Powerful supporters of Stockton’s privatization were annoyed, even outraged, by having to go through the motions of public debate. The head of the city’s water department was fired for asking hard questions about the plan to privatize. Even the local newspaper was pressured to oust its city hall reporter, who did nothing more than what is usually considered a journalist’s job—remaining skeptical of unproved claims and representing fairly the arguments of participants on both sides in the controversy.

The joy of documentary filmmaking is that it allows time for themes to evolve. As we followed our stories, it became clear to us that the fight over water privatization represented something larger: the conflict over perceptions of democracy, public participation, and citizenship. Protagonists in the water battle also began to play out our nation’s lack of consensus on the broader issues of national identity and values. Mayor Gary Podesto, Stockton’s leading advocate of utility privatization, dismisses privatization opponents as “activists” and calls them “the butcher, the baker, and the candlestick maker.” “It’s time,” he tells business leaders, “that Stockton enter the 21st century in its delivery of services and think of our citizens as customers.”

“I’m not a community activist,” counters orthodontist Dale Stocking, “I’m an involved citizen. If there’s an issue I care about, I get involved.”

Privatization of a basic public service like water raises these issues of democracy and citizenship because when a private company takes over the water supply, the formerly public conversation about priorities of water use and allocation becomes a private conversation and disappears from public scrutiny. This is happening at a time of increasing government secrecy and antiterrorism measures, which intensify the public’s distance from meaningful civic participation.

As one might imagine, “Thirst” was not popular among the major multinational water companies, all of them among the hundred largest corporations in the world. The major companies, their trade associations, and their backers at the U.S. Conference of Mayors condemned the film in frustration, unable to find errors and do more than grouse that the national broadcast, a screening on Capitol Hill, and community showings have “outed” their activities as something other than salvation for cash-strapped cities. Since we completed the film, the battle over the future of water has intensified. We hope the film dramatizes that we, as a nation, are far from consensus on the future of our most basic natural resource.

Alan Snitow and Deborah Kaufman are documentary filmmakers. More information about “Thirst” can be found at www.thirstthemovie.org, including an accompanying study guide written by the Sierra Club Water Privatization Task Force.