When Melissa Jeltsen Googled Lorena Bobbitt’s name a few years ago, she was surprised to learn that the woman known for cutting off her husband’s penis in 1993 had started a charity to help victims of domestic violence. Jeltsen covers domestic violence for HuffPost and was a child when that incident happened. She says she didn’t remember learning about the domestic violence aspect of the Bobbitt case. “In the cultural memory, she was just a vindictive woman who lost her mind and assaulted him.”

Jeltsen contacted Bobbitt and eventually convinced her to be interviewed for an article published in December 2016, “Lorena Bobbitt Is Done Being Your Punchline.” Besides examining Bobbitt’s legal case in light of contemporary views about domestic violence and sexual assault, Jeltsen calls out her harsh treatment by the press—a theme that’s striking in the “Lorena” docuseriesthe article inspired, which debuted on Amazon in February.

“As I was revisiting the media coverage and the footage of the trial I was just so shocked,” Jeltsen says. Clips in the four-part series show that it wasn’t just late-night comedians and tabloids that overlooked the record of sexual and physical abuse in Bobbitt’s marriage; leading media outlets made questionable ethical decisions that further sensationalized the case. For instance, while a Vanity Fair article included a lengthy discussion of the marital rape aspects of the case, the photographer for the magazine persuaded Bobbitt to pose in a bathing suit in a pool, reinforcing the “hot-blooded Latina” narrative that dominated the cultural conversation.

A year later, in 1994, the Violence Against Women Act was passed, the first federal legislation acknowledging sexual assault and domestic violence as crimes, which expanded services and protections for victims.

More recently, the #MeToo movement and revelations of misconduct by dozens of high-profile men ignited a torrent of media coverage of sexual assault—including accusations of wrongdoing by top news anchors, editors, reporters, photographers, and radio hosts. But journalists who cover domestic violence say the topic hasn’t had the same cultural reckoning among the public or the press. Despite the recent popularity of documentary series like “Lorena,” media coverage of domestic violence has not yet led to widespread understanding of just how pervasive a problem it is.

Jeltsen and others are finding ways to elevate reporting on domestic violence, while also advocating for more sensitivity and accuracy in how it is covered

Given the historical underrepresentation of women in many newsrooms, particularly in leadership positions, it’s not surprising that reporting on domestic violence has not gotten the same level of attention as some other social issues. “I think that did shape the coverage,” Jeltsen says. “If it’s only men telling the stories, what lens are they looking through?”

Jeltsen and other journalists are finding ways to elevate reporting on domestic violence, while also advocating for more sensitivity and accuracy in how it is covered. Reporters are exploring how factors like race, class, and immigration status can influence victims’ vulnerability to domestic violence and willingness to report it, as well as how the criminal justice system and service providers deal with these cases. They’re also examining the roots of the problem, efforts to rehabilitate perpetrators, and patterns of abuse, such as strangulation, that are more likely to end in the victim’s death.

While domestic violence can include sexual assault, it also refers to physical, emotional, or psychological actions or threats to gain control over a current or former intimate partner. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 in 4 women and 1 in 7 men have experienced severe physical violence by an intimate partner; 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have experienced some form of physical violence by an intimate partner, such as slapping or pushing. But the limitations of national government surveys, gaps in crime data collected by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and under-reporting by victims have made it difficult for journalists to obtain statistics capturing the scope of the problem, as well as to convince editors and readers to care. Finding sources willing to speak openly about their experiences with domestic violence can also be a challenge, particularly when an abuser is still a threat.

Based on 2016 homicide data collected by the FBI, a study by the nonprofit Violence Policy Center found that, in the U.S., 962 women that year were killed by a husband, common-law husband, ex-husband, or boyfriend. However, neither Florida nor Alabama submitted data and the relationship of perpetrator to victim could not be determined for all homicides. A study by James Alan Fox and Emma E. Fridel at Northeastern University found that 44 percent of women killed between 2007 and 2015 were killed by an intimate partner, compared with 5 percent of men who were killed by an intimate partner.

“It’s very difficult to report on because there’s already so much blame that exists beneath the surface for women who are in abusive relationships,” Jeltsen says. These judgments can include speculation that she “must’ve done something to deserve it” or believing “it would never happen to me,” as well as questioning why women in these situations don’t just leave. In order to address those assumptions, Jeltsen says, it’s important to present the complexities of the decisions a woman may face, like a husband who threatened to kill her, or a lack of financial resources, or a reluctance to report a crime that could lead to a lengthy prison sentence, particularly for an African American man. Jeltsen has written features that highlight broader themes about the perpetrators and victims, such as “The Super Predators: When the Man Who Abuses You Is Also a Cop” and “The Quiet Crisis Killing Black Women,” about how racism in the criminal justice system and society at large makes black women less willing to report domestic violence crimes.

Describing her feature on black women’s distrust of the criminal justice system, Jeltsen says: “I couldn’t have written that story the first year I was on this beat because I didn’t understand those nuances as much.” Jeltsen began reporting the story after Delashon Jefferson was killed by her boyfriend, whom she had reported to the police for assaulting her and threatening her with a gun. She and other witnesses decided not to cooperate with the prosecution if the case went to trial, so he was granted a plea deal that included probation, drug testing, anger management classes, and a prohibition on owning a gun—although within a year he fatally shot her in front of their young son.

“You look at that from the outside and you’re like, ‘The criminal justice system failed,’” Jeltsen says, explaining that she could imagine people reading it and being judgmental about Jefferson’s decision. But she had come to understand that reluctance given how the criminal justice system treats black men. “Talking to her family and people in her community, I can understand why she did not want to be responsible for him spending 15 years behind bars.”

The failures and limitations of a criminal justice system long dominated by men and the toll on children are powerful themes in the documentary “Home Truth,” directed by April Hayes and Katia Maguire. Filmed over nine years, it chronicles Jessica Lenahan’s fight to seek justice for her three young daughters, who were murdered by their father in 1999. Lenahan (formerly Gonzales) sued the town of Castle Rock, Colorado and its police department for not enforcing the restraining order she had been granted against her estranged husband Simon, who had engaged in threatening behavior after their relationship ended. Officers didn’t investigate the girls’ disappearance the night he took them and shot them, despite the court order restricting his contact with the family. The Supreme Court ruled 7-2 against Lenahan in 2005, raising questions about the value of restraining orders and whether they’re taken seriously by law enforcement and the judicial system.

One of the most galling moments in the film is the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s flippant comment that Castle Rock was also a 1920s dance.

“We included that Scalia joke because that was something Jessica said really bothered her,” Maguire recalls. “She felt the justices were very cavalier in this moment when she was getting a decision about the most traumatic thing that happened in her life.”

Restraining orders were introduced in the 1970s and in Lenahan’s case, a Colorado court determined that Simon’s meetings with his daughters had to be arranged in advance. But questions have been raised about the effectiveness of these orders and whether gender bias in policing has impacted how they are enforced. Jeltsen’s article about domestic abuse by police officers cites a 1991 survey of more than 700 police officers finding that 40 percent admitted that they had “behaved violently against their spouse and children.”

Even witnessing domestic violence can have long-term effects on children’s mental health and is associated with offending as an adult. A 2011 Department of Justice report found that 1 in 9 children were exposed to some form of family violence in the past year, mostly witnessing violence between their parents or a parent and partner. About 450 children on average are killed by a parent every year in the U.S., according to an analysis of FBI data.

“Home Truth” makes the girls more than just victims by showing many home videos Lenahan shared—holidays and birthday celebrations juxtaposed with footage of their funeral—which also reveals how domestic violence can impact what may seem like a typical home. But the film is primarily about the toll of her lengthy legal and advocacy battle, particularly how it impacted her son, Jessie. He acknowledges conflicting feelings in interviews throughout the documentary, commenting that Lenahan “chose the case over me” and later saying, “I can’t even begin to judge my mom because I haven’t lost my children.” At different points, Lenahan admits, “He wants me to be unbroken and I’m not … I feel pretty deserving of his distance from me.”

The prolonged time frame of domestic violence cases is critical for journalists—and readers—to understand

Maguire says she and Hayes were grateful for how generous and open Lenahan and her son were, and tried to give an honest portrayal of their bond, including the tension between them at times. They filmed Lenahan and Jessie separately and together over the years, hoping to show “how two members of a family who have gone through this really traumatic experience of losing these girls process things differently,” Maguire says. “We definitely made choices in terms of what to tell and what not to tell. As in all families, really hurtful things were said at times, and we didn’t want to shy away from that. We also wanted to make sure it was fair to our overall sense of what their relationship was and where it was heading.”

Another challenge for the filmmakers was the long wait to find out if Lenahan would achieve anything through her fight. They first met her in 2008, as she was taking her case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an attempt to get a regional body to take action after she lost her Supreme Court case. Lenahan became a collaborator, occasionally filming herself during the three years she waited for the commission to rule that the U.S. had violated her and her daughters’ rights—footage that shows her perspective and lets viewers experience some of her frustration. But it took another four years before the Justice Department issued guidelines on preventing gender bias in the way law enforcement responds to sexual assault and domestic violence.

For Rachel Louise Snyder, author of “No Visible Bruises: What We Don’t Know About Domestic Violence Can Kill Us,” published in May, the prolonged time frame of domestic violence cases is critical for journalists—and readers—to understand. “I think the most important thing to consider when reporting on domestic violence is what most people are up against with time,” she says. “Domestic violence is ongoing, oftentimes for years.”

Because of that lengthy timespan, as well as the impact of trauma on memory, someone who has experienced or even witnessed violence can appear to be unreliable when describing what happened to them. In an article for Nieman Storyboard, Snyder recently analyzed her 2013 article for The New Yorker, “A Raised Hand: Can a new approach curb domestic violence?”—an assignment she landed by pointing out that if women were killing their husbands at such an alarming rate it would be front-page news across the U.S. She also has written about the under-examined link between domestic violence and traumatic brain injury, which can be caused by physical blows as well as strangulation and losing consciousness, and says she uses various strategies to help sources recall past events.

“What I have people do is recount their stories again and again to me,” she says. “In any traumatic situation, we know memory is faulty. But if I hear a story five times, some of those details will be recurring.” She also asks sources to write out a timeline and draw a bird’s-eye view of the scene, which can prompt details they’ve buried to rise to the surface. “It’s like it loosens them up,” Snyder says. “As they’re focused on drawing, it allows their memory to kick in.”

In order to protect the identity of victims, who in many cases are still vulnerable to future violence, Snyder says she’ll identify someone as 30-something instead of giving a specific age or say she lived in the northern part of New York instead of naming a city. She has heard comments like “he broke CDs and threatened to slit my throat” often enough during the decade she has covered domestic violence that she feels comfortable including that detail in a story without it being obviously linked to a specific case.

Inevitably, these are painful stories to share—and hear. Reporting on this topic requires empathy and patience, particularly when sources are still in danger and may change their minds about being in an article or need time to weigh the risks. Snyder points out that patience and restraint are also important during interviews, when she has learned to wait out difficult silences and resist the urge to interject or react. “You have to fight against every instinct to comfort them and just allow them to sit in that awkward space and experience that moment again,” she says. “Because that’s when you’re going to hear the truth.”

Snyder says that technique also applies to her conversations with perpetrators, mentioning a man she interviewed in prison who broke down and let out “an animalistic noise” after describing “the worst thing somebody can do to someone they know.” That perspective can be much more difficult to capture, she says, explaining that she has found that victims are much more willing to talk than the perpetrators. “We don’t spend enough time trying to find out why violence happens in the first place,” she says.

Snyder also mentioned that domestic violence against men and within the LGBTQ community has not been discussed as much as violence against women, in part because of stigma. “There’s deep shame associated with being a victim no matter who you are, but that shame is amplified when you’re a man.”

Lauren Justice, a photographer based in Madison, Wisconsin, set out to explore the perpetrator’s perspective with a project that was published in The New York Times in March: “What Would I Have Done if I Would Have Killed Her That Night?” During a three-year mentorship program sponsored by the Anderson Ranch Arts Center, Justice began photographing women she met at a shelter for victims of domestic violence, initially intending to document how they started over after leaving an abusive partner. “Then I realized I wanted to focus on the root of the issue,” she says. “I wanted to talk to the people who were perpetrating the abuse.”

VICTOR, 35: “As soon as the argument is done, I feel horrible. I don’t win by calling anybody names. I don’t win by being physical with anybody. You know, it’s a lose-lose situation. And I get very upset. I’m still trying to learn things. I’m willing to learn and take these classes that I’m in now to become better. But I can’t blame everything on my stepfather or my mom because ultimately I make my own decision and nobody should be able to make me angry no matter what the situation is. I make myself angry, and I can’t control nobody but myself.” Lauren Justice

She first interviewed a local professor who had run batterer intervention programs, research that helped her understand how they worked before she connected with a facilitator who introduced her to Victor, one of the men she eventually interviewed and photographed. After speaking on the phone, they met on “neutral ground”: an Arby’s, where she explained what she was hoping to do with the project. At that meeting, she didn’t turn on her recorder or take any photos. “I knew from the beginning it was going to be a very long process and the main thing was to be patient and persistent,” she says.

By attending the batterer intervention class, she gained a deeper understanding of the situations the men described—about their childhood, their dating history, and their life experience—as well as whether they expressed any empathy or accountability, factors program facilitators told her they use to measure success. “Being present for those conversations in the class helped guide my interviews, and when to ask a question again or a different way,” Justice says.

In some cases, she was able to speak with the men’s current and former partners and included their perspective about the impact of the class in her essay. One woman who resumed a relationship with her partner Jake after a few years apart is quoted saying, “You can tell that he was taught a different way on how to handle himself through that class,” while another woman who is no longer with her former partner said she didn’t observe a positive change after he completed the class.

Justice was working part time at a shelter while she pursued this project, and in the essay accompanying her photo series writes about “listening to terrifying stories of survival” from the women, then attending the batterers intervention class and hearing “these men’s minimizations and denials”—as well as the breakthroughs that sometimes happened. She also discloses her own history of being in an abusive relationship, a fact she shared with the men if they asked.

Justice’s essay ran in the Op-Ed section of the Times, but she said she worked hard not to let her personal experience or opinions influence how she presented the men in her series, who reveal a range of self-awareness about their behavior. “I spent a lot of time talking to the facilitator after classes and also a network of advocates,” she says. “I also had a really great support system through the journalism community and that mentorship program. Having that balance was really important.” In addition, conversations with the program facilitator and researchers who study domestic violence helped her ensure that the information she included in her essay was “in line with what the experts had experienced as well.”

Domestic violence typically happens in private, perpetuated by secrecy, shame, and silence

One of the things journalists who cover domestic violence wrestle with is finding angles to report on that go beyond describing what happens to victims—ideally, giving readers a fuller perspective on the complexities of this crime. Editors who green-light pitches are known for asking, “What’s new about this?” and, after spending a while reporting on domestic violence, it becomes apparent just how common it is. As much as media coverage of mass shootings follows a familiar narrative, too, those events draw camera crews. Domestic violence typically happens in private, perpetuated by secrecy, shame, and silence.

For the series “Behind the Front Door – Inside Domestic Violence in Greenwich,” Emilie Munson wanted to explore how those factors impact the way that domestic violence is dealt with in a wealthy community in Connecticut. The five-part series ran in Greenwich Time in late 2017, with separate installments focusing on the victims, the police, the courts, the children, and the abusers. Munson was hired to cover education for the paper, but ended up spending 16 months working on this project. “Domestic violence is the number one violent crime in Greenwich and it is the second most investigated crime overall—second only to larceny,” Munson says. “We wanted to explore the role of wealth in domestic violence in particular and how that can exacerbate the problem.”

She first met with staff at the YWCA Greenwich, the only certified provider of services to domestic violence victims in town, and did training on how to do trauma-sensitive interviewing with victims. Munson says it was difficult to find survivors who were willing to share their stories, particularly in a community where people are “very careful about media exposure” and often reluctant to speak to reporters. Although she interviewed a dozen survivors, not all of their stories made it into the series, which also included articles about the Greenwich Police Department’s domestic violence unit and the way that perpetrators can use the court system to harass and financially bankrupt their victims.

Some articles, like “Wealth Does Not Protect the Abused” and “Male Power, Privilege Drive Most Abusers,” directly address the intersection of money, power, and gender—illustrating how wealthy perpetrators can control their victims by denying access to bank accounts and exploiting their partners’ fear of challenging men who wield influence in the community.

Munson says she became interested in the law enforcement response because police officers are often the first outsiders to find out about domestic violence the victim has kept secret from family and friends. “It might be that spur of the moment 911 call that brings the first person into the home to see there was an issue,” Munson says, adding that she also wanted to explore the emotional toll on officers who respond to sometimes horrific scenes. Besides many interviews with the head of the domestic violent unit, she spoke with at least four other police officers who work in the unit, saying they were very candid when discussing “the strengths and shortcomings of the police apparatus to respond to these cases” as well as describing the relationships they built with survivors.

For her article, “A Child Silenced by Domestic Abuse,” she ended up profiling a woman who had experienced domestic violence as a child and years later helped her daughter escape a similarly violent marriage—illustrating the multigenerational effects of domestic abuse. That article was accompanied by a list of symptoms of domestic violence exposure for children in different age ranges, while others in the series listed domestic violence hotlines and local service providers. Munson also hosted Facebook Live events to answer readers’ questions throughout the publication of the series, saying the response was “overwhelmingly positive.” The questions ranged from inquiries about the criminal justice system—e.g. “Why don’t judges enforce court orders to protect women?” and “How often do DV perpetrators end up in jail versus in a diversionary program?”—to curiosity about the reporting process, like “Have you ever felt unsafe reporting these stories?”

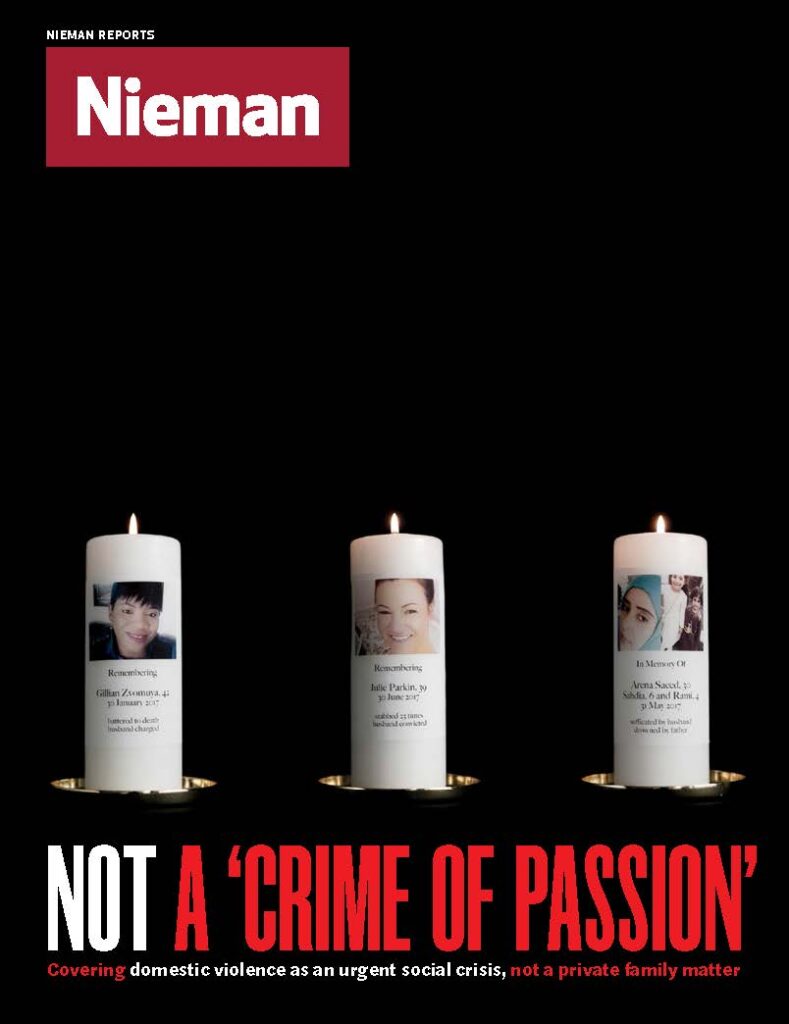

Listing a domestic violence helpline with articles about this topic is one of the recommendations in media guidelines issued last year by the U.K. feminist group Level Up. Titled “Dignity for Dead Women,” the guidelines offer best practices for journalists reporting on domestic violence deaths. They include tips like clearly placing the responsibility on the killer (without using clichés like “jilted lover”), naming the crime as domestic abuse or violence (not a “tragedy” or “horror”), and avoiding insensitive or trivializing language and images (bearing in mind the impact on children who may read graphic reports about their mother’s death).

Rossalyn Warren, a London-based freelance reporter who was an advisor for the guidelines, says she was approached by the group because of her criticisms of the way the British press cover women murdered by a current or former partner (about two deaths per week in the U.K.). “I think one of the biggest issues is the idea of the motivation of the perpetrator of domestic violence. A lot of the narrative in these stories is centered around something the victim did that led to their murder,” Warren says.

Warren says that type of victim blaming is apparent in articles that suggest a man was jealous because he found out his former partner had a new boyfriend, or “flew into a rage” when he learned she was going to leave him. Although leaving an abusive man is when women are at high risk of being killed, articles that fail to provide context about that history of violence misinform the public by framing a murder as an incident rather than the culmination of a pattern.

In 2016, Warren wrote an article for BuzzFeed News about “The Men Who Murder Their Families,” pointing out that in news coverage of cases of murder-suicide in Britain and Ireland, “[T]he press focused on how the men were upstanding members of the local community, with little mention or detail of the women and children who had been killed.” Instead of quoting researchers who have studied these types of “family annihilators,” journalists tended to quote neighbors or friends describing the perpetrator with phrases like “a real gentleman” and “a good man.”

The Level Up guidelines recommend centering an image of the deceased woman, and including a photo of the perpetrator lower in the article. The report also provides a link to royalty-free images of models taken by Laura Dodsworth, who was commissioned by Scottish Women’s Aid and Zero Tolerance to take a series of photographs that “do not show bruises, or physical violence”—highlighting that domestic abuse can also be emotional, financial, and verbal.

Although Warren has found that younger journalists in the U.K. are more aware of domestic violence and committed to covering it fairly, particularly since the #MeToo movement, she feels that this topic has not had the same impact yet. “I think there hasn’t been a great reckoning with the scale of domestic violence in society,” she says. “Training within newsrooms would be hugely beneficial.”

For instance, the Level Up guidelines cite research showing that narratives of romantic love in media reports about domestic abuse deaths can lead to lighter sentencing in court—even when there is clear evidence of violence preceding the murder. “Every article on domestic abuse is an opportunity to help prevent further deaths,” the guidelines advise, noting that perpetrators often share behavioral patterns that reveal risk. In the U.S., one of those risks is being involved with a violent partner who owns a gun.

Dawn Wilcox, a school nurse in Plano, Texas, started tracking women and girls murdered by men in the U.S. after she noticed the outpouring of sympathy following the killing of a gorilla at the Cincinnati Zoo and a lion shot by a Minnesota hunter in Zimbabwe. Hoping to generate similar outrage about female victims of violence, she started a public spreadsheet called Women Count USA, which lists the names, ages, photographs, locations, and cause of death of women and girls allegedly murdered by men. She also includes the names and photos of the alleged perpetrator, suspect, or person of interest and other details about the crime, such as whether the man had been in the military or worked in law enforcement—in part because the public can’t access officers’ disciplinary records involving abuse and also “they’re deciding whether or not sexual assault cases move forward.”

Wilcox estimates she has documented about 1,650 cases on her 2018 spreadsheet so far. “I only have women on my list that journalists cared enough to write about, so I haven’t even done open records requests. You’d have to go to each police department because you can’t rely on federal statistics.”

Research shows that narratives of romantic love in media reports about domestic abuse deaths can lead to lighter sentencing in court

“One thing I’ve come away from this work with is the absolute horror of witnessing how brutal, callous, and vicious men are when they kill women,” Wilcox says. “I want people to scroll though my spreadsheet and I want them to be shocked. I want them to be sad and angry and I want them to act and care.”

Wilcox uses the phrase “corrective femicide” in her spreadsheet, highlighting cases where men rationalized a killing with excuses like “he heard her talking to another man” or she “disrespected him.”

As someone who has been in an abusive relationship, she views the use of “survivor” or “victim” as a personal choice, although she has concerns about removing the word victim from this discussion. “It doesn’t bother me to be called a domestic violence victim or a sexual assault victim because I am both—I don’t think it portrays me as weak,” she says. “But for me when you eliminate the word ‘victim’ it clouds the mind that someone did something to someone.”

Her media criticism and advocacy stems from recognizing the power of the press, to change laws as well as public opinion. The latter role is critical for improving the public’s understanding of domestic violence.

After all, she points out, “These are people who are going to be on juries”—and can ultimately impact whether the perpetrators are held accountable for their actions.

*Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the percentage of women killed between 2007 and 2015 by an intimate partner as found by a Northeastern University study. It is 44 percent, not 45.

An earlier version of this story said Lauren Justice was volunteering at a shelter while she worked on her photo project. In fact, she was working part time at a shelter.