Reporting on Health

Few topics receive more media attention today than the topic of health. Yet, in the view of some journalists, many of the stories being told about health are not ones journalists want to tell or that members of the public need to hear. As Andrew Holtz, a freelance health reporter and president of the Association for Health Care Journalists, observes, “… stories I think need to be told, are often not the ones that easily sell. My personal frustration is not the issue, but we should be concerned when journalists are inhibited from the work of sustaining an informed and involved citizenry.” – Melissa Ludtke, Editor

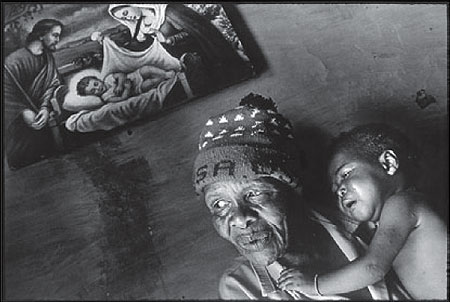

Boitumelo Mogorosi, three months old, who is HIV positive and whose mother has AIDS, lives with and is cared for by her grandmother, Emily Mogorosi, 68, in Thaba ‘Nchu, South Africa. September 2002. Photo by James Nachtwey.

For a photographer, a single word can be worth a thousand pictures.

During the past 20 years, my work has taken me to the darkest corners of the planet—man-made infernos that make Dante and Hieronymus Bosch look like straight, social documentarians. To my eyes, recent history has unfolded like a serial apocalypse. “Genocide” is a word so heavily freighted with memory and responsibility that it caused the most powerful, technologically advanced nations in the world to turn their backs as more than a half million people were slaughtered in the space of a single season with weapons that were no more than farm implements. The destruction of food as a weapon of mass extermination is a phenomenon so unthinkable that it makes a euphemism of the word “famine.” “Ethnic cleansing” is a sanitized term for the wholesale murder, rape and mass deportation of one’s neighbors. The uninhibited military assault on civilian populations politely passes as “civil war.” Such words have become synonyms for the bloody homestretch of the 20th century.

The images conjured by these words burned a hole in my consciousness that I can only attempt to fill with the stark hope that publishing pictures in the mass media not only informs, but also makes an appeal to stop the madness, lend a hand, restore humanity.

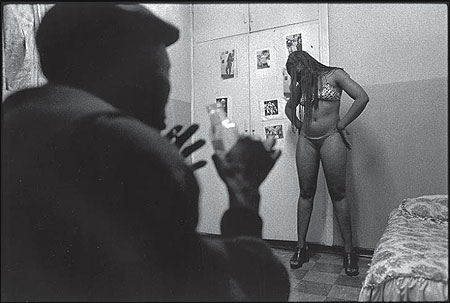

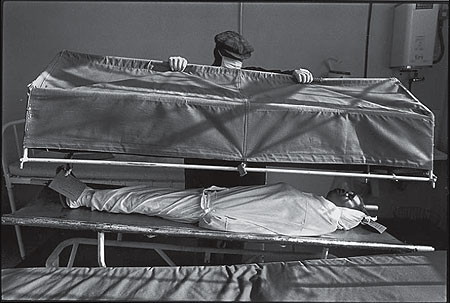

As we entered the third millennium, the plague years descended upon sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS will probably wipe out more people than all the wars, famines and natural disasters of the past decade put together. The drama of the AIDS epidemic is more subtle than the older calamities that rocked the African continent. It plays itself out behind closed doors. People are suffering silently, in hospices and hospital wards and in isolation inside their homes. Most Africans cannot afford the cocktail of drugs that forestalls the effects of the disease. AIDS is a death sentence, and people are dying quietly, one by one, in the millions.

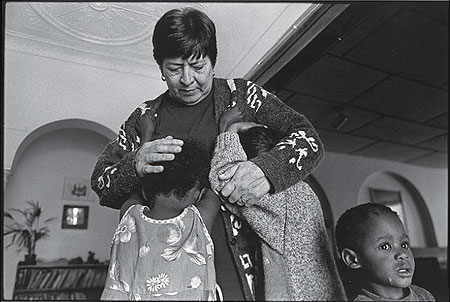

The frontline troops in this war are the gentle souls who have committed themselves to the saintly task of attending the dying. Grass roots NGO’s and Christian missionaries bathe, feed and lend emotional support where it is most needed, but they are waging an uphill fight. As I accompanied caregivers on their rounds in shantytowns, hospices and farms, I was awed by their selfless, unsung devotion. Where hope no longer existed, they replaced it with comfort and dignity.

In the early 1990’s, I spent a good deal of time in South Africa documenting the epic battle to overthrow apartheid, culminating in the election of Nelson Mandela. According to statistics, South Africans are being literally triaged by an invisible enemy that is oblivious to the courage and idealism with which they prevailed against impossible odds in their political struggle. The AIDS epidemic is a devastating postscript to a story that embodied the best that humanity has to offer; there is no alternative but to defeat it.

Its defeat will only be accomplished through awareness and education, both within the countries affected and in the rest of the world, which is morally obliged to lend support and assistance. My goal as a photojournalist has always been to help create that awareness.

When a photo editor and I approached the editors at Time with the idea of a story about AIDS in Africa, they were extremely supportive. The magazine let me stay in the field for more than two months and sent a senior writer to do in-depth interviews. This cover story, which appeared in February 2001, included 10 pages of photographs and 10 pages of text.

I am continuing my visual documentation of the AIDS epidemic, paying special attention to caregivers, with the continuing interest of the editors at Time, the generous assistance of the Alicia Patterson Foundation, and a grant from the Kaiser Media Mini-Fellowships in Health.

Rosinah Motshegwa, 29, HIV positive, lives with her two unemployed brothers in Khutsong, South Africa, and is tucked into bed on a sofa in the sitting room by a caregiver from the Carletonville Homebased Care Program. August 2000.

Children who are HIV positive are comforted by Dawn Bell, an administrator at the Sparrow Ministries, which serves as a home and daycare center for those infected with the AIDS virus, in Roodepoort, South Africa. August 2000.

A brothel in Harare, Zimbabwe, where prostitution is openly practiced even though it is illegal and is one of the most common ways in which HIV is spread. July 2000.

A patient who has just died from AIDS-related tuberculosis at Beatrice Road Infectious Diseases Hospital in Harare, Zimbabwe, is covered by an orderly before being transported to the morgue. October 2000.

James Nachtwey has been a contract photographer for Time since 1984. He has devoted himself to documenting wars, conflicts and critical social issues worldwide. His book, “Inferno,” was published by Phaidon Press in 2000.