“Stories stalk you. Stories beguile you. They bewitch you. It’s not easy to fend them off, even when you’ve vowed you will,” Susan Orlean writes in our Fall 2023 issue, which commemorates the Nieman Foundation’s 85th anniversary.

Over 400 Nieman alumni gathered at Lippmann House in October for the occasion, where during the reunion weekend, one event asked fellows to respond to a simple prompt: Tell us the story you couldn’t let go of.

Five of those stories, delivered live at the reunion, are featured in this issue. These stories have liberated low-income patients from hospital debt, landed a fellow in a Zimbabwean prison, delved into the inner workings of libraries, joined together two fellows in Ukraine, and chased down the circus of Alabama politics.

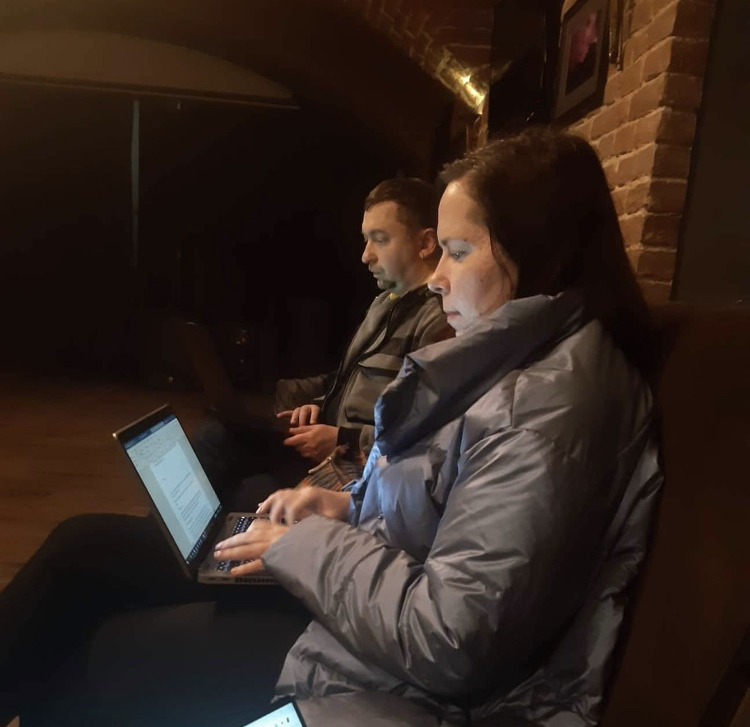

In November 2022, I saw my former home in Kyiv in flames on live TV following a Russian missile attack. Moscow was targeting energy infrastructure across Ukraine to cause blackouts, often by firing up to 100 missiles at once to overwhelm Ukrainian defenses. This often resulted in major damage to civilian infrastructure — schools, museums, universities — and residential areas, like the ordinary five-story building in the leafy Pechersk neighborhood where I lived for much of my life in the Ukrainian capital.

I had been safely out of Kyiv by that time, but the attack served as a painful reminder of the personal toll the war has taken on myself and other Ukrainian journalists. We were not like the prominent war correspondents who travel to a faraway warzone for a three-week deployment and then go back to the comfort and safety of their peaceful countries. The war had come to us and there was no way to escape the emotional impact it left, even if we were physically far from the front lines.

Inevitably, this emotional attachment to the story raised difficult questions about how we should cover it.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Ukrainian society responded with unprecedented unity, and the media community was no exception. As I observed in my role as a media analyst at BBC Monitoring's Kyiv bureau, the coverage was defiant and patriotic, amplifying Ukraine's heroic struggle for freedom and rallying behind President Volodymyr Zelensky. There was an unspoken consensus that this is the only way to respond when your country is under attack and that any political disagreements or criticism of the authorities should be put aside, since any bickering would only play into Russia's hands.

But as the initial shock of the invasion wore off, the question "what's next" began to be openly asked in the Ukrainian media community. What is our role as Ukrainian journalists in wartime? What comes first, being a journalist or being a citizen? Should we raise inconvenient topics, such as corruption in the military? And if so, how do we go about the fact that exposing it could, for example, undermine vital aid from Western allies?

Both in journalism school and at the BBC, where impartiality is one of the key editorial values, I have been taught to strive for balanced, objective reporting. But nothing prepared me for having to effectively make a choice between my identity as a journalist and my identity as a Ukrainian.

While this choice was painful, it was not new to me. I faced it when Russia annexed my home region of Crimea in 2014. I had my own strong opinions on what happened — and grappled with the profound impact the annexation had on my family — but I managed to leave them out of my reporting, because I felt that it was important to show the full picture and give sufficient attention to the stories of people I may disagree with.

But this time, the scale was different. We were talking about the survival of the entire country, the one I love deeply.

Gradually, Ukrainian journalists started discovering solutions. While national TV is still speaking in a united, highly patriotic voice and often attracts criticism for its excessively pro-government coverage, critical reporting is thriving online, where you can find numerous investigations and other stories on sensitive issues.

It appears that the Ukrainian media community has been gradually shifting to a new consensus that it is important not just to win the war, but also not to turn into Russia in the process.

Ukrainian soldiers are fighting not just to preserve the country's territorial integrity. They are also fighting for a Ukraine that is free, democratic, and pluralistic — everything Russia is not. If we do not talk about problems, we will never solve them and our country would only become weaker because of that.

But the way Ukrainian journalists have stood up for their right to do critical reporting even during the war makes me optimistic that it is not going to happen.

While doing quality journalism is important for society, it is also important for us, journalists, as human beings. Even though hearing missiles striking my city was the scariest thing that ever happened to me, I found solace in the fact that I was doing something useful and meaningful — telling the story of the war in Ukraine to the audiences around the world.

It has been 20 months, but this mission still fills my heart with meaning and hope.