A 30,000-foot-tall cloud of black smoke billows from Whatcom Creek after a gasoline pipeline leaked into the creek and was somehow ignited June 10, 1999, in Bellingham, Washington. Two 10-year-old boys and a teenager died. Photo by Angela Lee Holstrom, The Bellingham Herald. Courtesy of The Associated Press.

I wish I could figure out what makes environmental journalism so mysterious to so many people in our business. When done right, it’s passionate storytelling with a hard-nosed quest for truth, and this should be the hallmark of our craft.

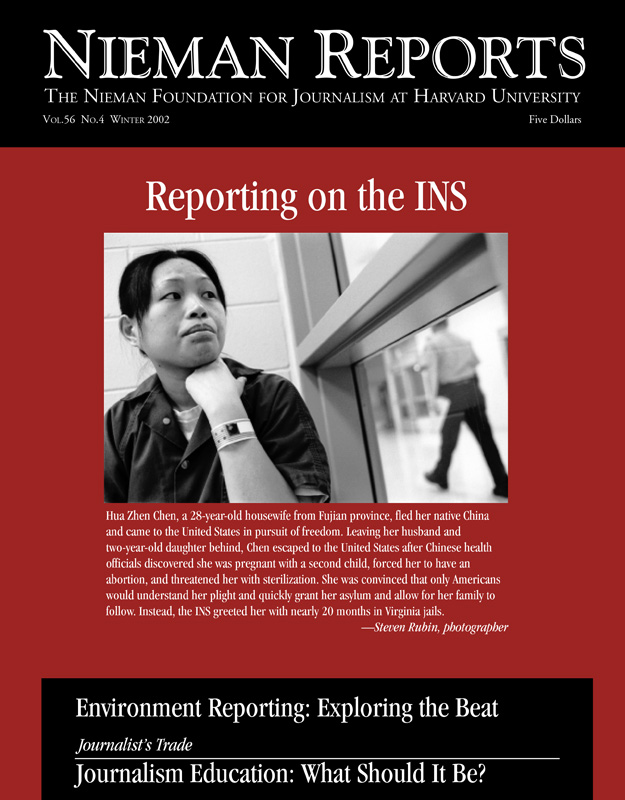

Yet I remember having a chat at a St. Louis hotel in the mid-1990’s with one of the nation’s most prominent newspaper editors, a Pulitzer Prize-winner who had recently written for Nieman Reports. Our conversation occurred after one of those inspirational writing conferences sponsored by the Poynter Institute. Our creative juices were flowing. She asked if I thought the environment beat was really the best place for me to achieve my potential as a writer and then murmured something about all those dull scientific documents and dull government bureaucracy. It was a fair question. After all, there is a lot of gobbledygook to decipher. But, as with any type of journalism, what readers read should not be burdened by extraneous details of the often cumbersome reporting process it took for us to get the story to them.

Stories From the Frontlines

Let me illustrate the junctures at which reporting and storytelling merge by sharing two stories involving hospital patients, both of whose situations were tied to environmental reporting projects.

Kim Tolnar was an Ohio woman in her 20’s, newly married and on a promising career path when her body was ravaged by leukemia. Her disease was so advanced that she had to spend nine months in one of the nation’s top cancer centers in Seattle. One night, when her anguish was particularly fierce, Kim told relatives she thought God had sent her to the Pacific Northwest to die. She tried pulling out a tube from her chest. Her father, Kent Krumanaker, used his loving hand to intercede and his calming voice to talk her out of giving up.

I describe this scene—this dramatic moment—because it illustrates how a seemingly dull and complicated environmental story can have gut-wrenching human elements.

Many people had been suspicious of what lies beneath the River Valley school campus in central Ohio, where Kim and others attended classes for years. The schools were built in the early 1960’s on land that had been a military dump. The Ohio Department of Health eventually recognized a high rate of leukemia among River Valley graduates. The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) launched what has become the largest environmental investigation in the state’s history.

Environmental activist Lois Gibbs (whose former neighborhood near Niagara Falls faced similar toxic threats in what became known as Love Canal) said that she regarded the risk in River Valley as greater than anything she experienced at Love Canal. And in a scathing, 110-page ruling issued by a federal labor judge in Cincinnati, former Ohio EPA Director Don Schregardus was accused of being more concerned with retaliating against an agency whistleblower than in protecting public health.

As the Toledo Blade’s reporter on this environmental story, what sticks in my mind is the tender resistance from Kent Krumanaker as he stood next to Kim’s hospital bed that night in Seattle and used his hand to counter what little strength his weak and frail daughter was able to muster. Their eyes communicated some message that changed their lives. Kim later explained it was a turning point in that her goal went beyond mere survival. Her father said there was “no doubt” in his mind God had spared her for a purpose. From that moment on, she and her parents devoted themselves to a quest for truth and accountability. The family returned home after Kim’s Seattle treatments and helped the community organize its crusade in 1997.

In another Seattle hospital, four years after Kim’s near-death experience, another father, Frank King, experienced every parent’s worst nightmare—and then some. King owns a car dealership in nearby Bellingham. For 23 years, he and his family lived comfortably in an affluent neighborhood where an underground gasoline line passes beneath a park. Their lives changed instantly on June 10, 1999, when the pipeline ruptured and allowed more than a quarter-million gallons of fuel to flow into a creek at that park. Minutes later, there was an explosion and parts of Bellingham were engulfed in a fireball.

King’s spunky 10-year-old boy, Wade, had been playing by the creek with his buddy, Stephen Tsiorvas. Both got caught in the flames and had burns covering 90 percent of their bodies. Virtually all the skin above their ankles had melted off. An 18-year-old named Liam Wood, who had been fly-fishing in another part of the creek, died instantly. The two 10-year-olds made it to the burn unit of a Seattle hospital alive, but their parents were told there was nothing they could do to save them. The boys died the following day, but were lucid enough to talk and ask their parents why they had to die.

Following Wade’s death, King led a crusade against the pipeline company and won. His efforts awoke bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. to the need for national pipeline reform. Wade’s father told a congressional committee he dabbed tears from his boy’s eyes as he explained to him what was going to happen. All he could do was tell him that heaven needed a catcher.

Both of these stories—illnesses attributed to toxic waste and death attributed to pipeline safety—have reams of scientific data that are much too sophisticated for most journalists to interpret on their own. But with assistance from experts in making the critical data understandable, each of these stories can then be told with the faces and experiences of children and their families, giving them the power of personal connection.

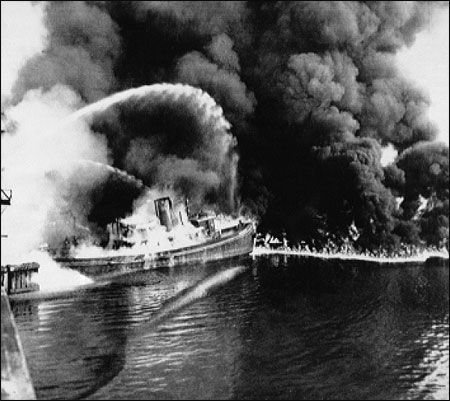

A fire tug fights flames on the Cuyahoga River near downtown Cleveland, where oil and other industrial wastes caught fire June 25, 1969. Photo courtesty of The Associated Press.

Power, Passion and Accountability

The power of scientific evidence. The passion of the engaged and the enraged. And the accountability of those who need to be held responsible. These elements are what we, as environmental reporters, strive to bring together. The mission of an environmental journalist isn’t different than that of other journalists; there’s just different kinds of information to decipher, assemble and tell.

“We do a good job of covering the news,” a managing editor of one of my former papers once said at a staff meeting. “Now we have to uncover the news.” By sniffing around on this beat, journalists inevitably find paper trails leading them to places where reporters usually end up—in the realms of politics, motivation and money. But for environmental stories, add science as well. Environmental reporting is about getting to the heart of political motivation; it’s about developing good instincts to know whom you can trust and who is trying to sell you a bill of goods. And it’s about sorting through rhetoric and seeing through the eyes of a lobbyist. It’s about knowing what makes people tick.

At the recent Society of Environmental Journalists’ conference, the late Rachel Carson’s legacy was honored in this, the 40th anniversary of her landmark book, “Silent Spring.” Carson was praised as a prophet and rightfully so. What she did in writing that book was challenge conventional wisdom about the pesticide DDT and awaken a quiescent nation to the idea that widespread, excessive use of pesticides could have dire consequences. By raising questions that needed to be addressed, she is now seen as one of the most influential women of the 20th century and certainly the environmental movement’s most influential person since the conservation era of Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir.

But Carson wasn’t looking for fame. She was a writer whose work had the power, passion and quest for accountability to make a difference for her generation and others. As a result of “Silent Spring,” scientists began looking for causal links between chemical exposure and cancer. In 1970, eight years after the book was released, Gaylord Nelson, a Senator from Wisconsin, became the driving force behind America’s first Earth Day.

Environmental News Is Now Harder to Convey

For a glimpse at how much more complicated environmental journalism has become since Carson’s era, I’ll defer to a speech I’ve heard Casey Bukro of the Chicago Tribune give on a couple of occasions. While writing about Great Lakes pollution in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, Bukro did a simple test while on a boat near Cleveland one day: He stuck his hand in Lake Erie. When he pulled it up, it was covered with black, filthy gunk. This was a time when many metropolitan areas around the country had smokestacks spewing so much pollution they had a constant haze hovering over them. Raw waste was being discharged into streams. In 1969, the Cuyahoga River—with petroleum products and debris floating on top of it—caught on fire one day. Once alerted to the toxic nature of these pollutants, many people believed that America’s environmental crisis was reaching a point of no return.

Bukro’s coverage of the Great Lakes, as well as some hard-hitting editorials published by the conservative Tribune, turned up the heat on the Nixon administration to do something about the spiraling concerns people had about the environment. In April 1972, Nixon and Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau signed the landmark Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, a pact in which the United States and Canada set cleanup goals for the lakes. Six months later, in October of 1972, Nixon—who created the Environmental Protection Agency—signed America’s Clean Water Act. That’s the law for which many of today’s sewage and industrial discharge limits are set. Both actions resulted in enormous costs and subjected Nixon to pressure from industry groups.

Bukro went on to become one of environmental journalism’s pioneers. He covered the beat for years and helped inspire change. But as he noted in a speech at Michigan State University in June 1996, environmental journalism became murkier as the Great Lakes became cleaner. Stories for today’s environmental journalist aren’t as obvious as sticking your hand in Lake Erie and seeing it covered with oily gunk, he said.

He’s right. This isn’t a clear-cut type of reporting anymore, nor was it really that simple in Bukro’s time. Scientific findings can be subtle, just as the changes they document can be subtle and important. To the dismay of some editors, answers don’t come neatly packaged as a guilty-or-innocent verdict in the courtroom or a vote tally on a proposed city council ordinance. By the mid-1990’s, a generation after Carson raised the specter of cancer being the possible end point for humans overexposed to chemicals, researcher Theo Colborn was building a case for less obvious impacts, such as birth defects and development disorders. These evolving scientific concerns are a reminder of how the environmental beat presents a series of moving targets, shifting as research veers off on new paths, and all the while setting new challenges for us as reporters and as storytellers.

I had the opportunity to meet Bob Woodward in the conference room of The Washington Post in 1992, while I was a Kiplinger Fellow at Ohio State University. Someone asked him to comment about the state of American journalism. Woodward slowed down his delivery to drive home the point he was illustrating with his thumbs-up, thumbs-down motion of his hand. “There’s too much of this,” he said.

It’s true that we live in an MTV world, in which well-educated adults use remote controls to flip through TV channels as if they were children with attention deficit disorder. It’s harder now to garner the public’s attention to inform—even to educate—people about dangers lurking beneath their feet, whether they involve hidden military waste, improperly maintained underground pipelines, or hazards that haven’t yet been reported.

As journalists, we have an awesome responsibility, and we have the power to inflame a community or put it to sleep. Nowhere is that sense of perspective more important than on the environment beat, because of the many gray areas in which we work. And those are what drive environmental journalists to see things that others don’t. Last year I wrote a four-day series about how the Great Lakes—the world’s largest collection of fresh surface water—will invariably become more valuable this century as the earth’s global water shortages become more acute. It was recently named Ohio’s top environmental project of 2001 by the Ohio Society of Professional Journalists.

Water. It’s so bland, tasteless and boring. Yet it’s so essential. It’s a dull topic, yet it’s also the emerging environmental issue of the 21st century as water supplies vanish, the population expands, and global warming sets in. Water is a fundamental resource like air and land—so basic that most Americans consider it a right we are entitled to use as we please. The reality is most of the world’s population today does not even have access to clean water.

I enjoy environmental journalism precisely because it’s not the most popular beat in the newsroom. And because it’s not predictable. But the amazing thing about doing this job is how quickly it humbles us when we move outside of our ecosystems. I know the Great Lakes like few other reporters do, but put me in an Arizona desert or a Pacific Northwest rainforest and I’m lost. Yet the parallels I find between those areas and my familiar territory fascinate me, as do the stories in each of those places that are waiting to be told.

Tom Henry reports on the environment for The (Toledo) Blade. He joined the newspaper in 1993 after spending four years at The Bay City (Mich.) Times and more than six years at The Tampa Tribune. He has won several awards for environmental writing and was the only journalist to appear at a roundtable session the International Joint Commission put together in 1997 to help commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement signed by President Nixon and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in 1972.