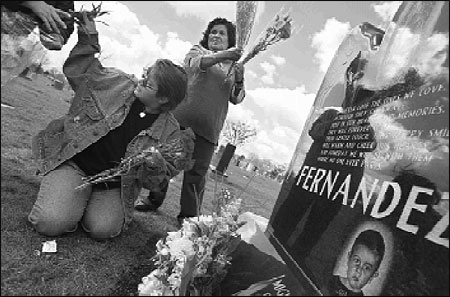

Mikey’s mother and grandmother visit his grave on what would have been his sixth birthday. When he was two years old, Mikey’s parents took him to the hospital as a precautionary measure after he bumped his head. He was accidentally given a sedative overdose by a nurse before a CAT scan at Rush Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago. Photo by Stephanie Sinclair, Chicago Tribune.

A Chicago boy’s tiny lips turned dark from a lack of oxygen as his mother’s scream echoed through the hospital. A registered nurse dashed to the examination table, cradled the boy’s limp body and ran down the corridor, panic gripping her voice, as she began to yell, “Blue baby! Blue baby!”

An elderly Kansas woman gasped for breath as she hoarsely called out for help, repeatedly pumping the call button for assistance that never came. As the minutes became hours she stopped breathing and her damaged brain began an irreversible shutdown.

A pregnant California mother struggling to give birth was given Pitocin, a common labor-inducing drug, but a miscalculation sent 35 times the ordered dose into her bloodstream, lethally coursing into the body of her unborn daughter.

Each of these cases—and thousands of other previously unacknowledged victims of nursing errors—were first uncovered as computerized statistics, anonymous clerical entries often obscured from public view by coded identities or confidentiality laws. Yet, after many months of additional reporting, these cases became the foundation of a three-day series published September 10-12, in which the Chicago Tribune reported that overwhelmed and inadequately trained nurses kill and injure thousands of patients every year as hospitals sacrifice patient safety for an improved bottom line.

Nurses provide first warning and rapid intervention for those too sick to help themselves. Analyzing more than three million computerized records, the Tribune embarked on a 10-month effort to quantify and document a national crisis of substandard nursing care. By themselves, the numbers proved stunning:

- Since 1995, at least 1,720 hospital patients have been accidentally killed and 9,584 others injured from the actions or inaction of registered nurses besieged by cuts in staff and other belt-tightening in U.S. hospitals.

- At least 418 patients have been killed and 1,356 others injured by registered nurses operating infusion pumps. All lacked training, or they claimed to be overwhelmed with too many patients. In many cases, harried nurses punched in the wrong dosage amounts on the pumps, turning an order for 9.10 milligrams to 91.0. Lethal calculation errors have become so prevalent that some nurses call them “death by decimal.”

- To compensate for understaffing, hospitals rely on machines with warning alarms to help monitor patients’ vital signs. At least 216 patient deaths and 429 injuries have occurred in hospitals where nurses failed to hear alarms built into lifesaving equipment, such as respirators.

- At least 119 patients have been killed and 564 others injured by unlicensed, unregulated nurse aides who are sometimes used to eliminate or supplant the role of registered nurses. Under a cost-savings program at some hospitals, housekeeping staff assigned to clean rooms have been pressed into duty as aides to dispense medicine.

In all, I relied on more than a dozen state and federal databases, which were painstakingly culled for nursing-related cases, then compiled into a custom database. Computerized records were cross-matched to paper files, such as court cases and death certificates, and supplemented by information obtained through hundreds of interviews.

The computer—and the raw statistics—were just a beginning. Information yielded patients such as Miguel Fernandez, the two-year-old Chicago boy who received a fatal overdose of drugs from his nurse who would later dash down the hospital hallway yelling “blue baby.” Another entry identified the victim only as #56893. Research later revealed that the five-digit code was Mary Heidenreich, 78, who was accidentally killed in 1999 by a morphine injection incorrectly administered by a registered nurse in Denver.

Just 15 states currently require hospitals to report medical errors, no matter how egregious the circumstances. Of those, only two states make the information fully public.

Two databases proved most useful in tracking nursing errors. The first is the MAUDE database compiled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which contains more than three million records detailing possible medical device failures. Conversely, the data can also be used to track instances of human error. Each record detailed a date and generic place, such as hospital or nursing home, but did not include victims’ names, name of the facility, or even the state. Like most computer databases, MAUDE data was a beginning for my reporting, not an end, a signpost to major thematic issues, such as patients who died because there were not enough nurses to properly monitor their conditions.

A second notable database was a national list of nurses disciplined by a state licensing agencies. Data are compiled by the National Council for State Boards of Nursing and include the nurse’s identity and type of violation. The council will not allow public access. However, files are mailed to each state, which means the data become part of the public record. Even so, Illinois licensing officials balked at turning over the list, but acquiesced after a brief skirmish with Tribune attorneys.

Information from these two databases was cross-matched with dozens of other public records, from court records to divorce files to home ownership. In many cases, records were found only on paper. Two weeks were spent sitting in a musty room with dozens of file cabinets as each Illinois disciplinary case was copied—I brought a portable copier that fits under the arm to facilitate the task. Then the information was entered into a spreadsheet program.

Files documented that drug-addicted nurses roamed from hospital to hospital without punishment. Nurses with serious felony convictions—from child molesting to aggravated drug trafficking—continued to work with impunity. Illinois officials, as well as other agencies nationally, agreed to withhold information that patients had died from public files if nurses agreed to quickly settle the cases. In one Chicago-area case, state officials erased references of a patient death from public files; the nurse had been found guilty of administering an overdose of chemotherapy. In a Utah case, a nurse who was found guilty of negligently killing a patient returned to work without suspension or additional training.

In all, 10 months were spent disassembling millions of computerized records, then combining and reassembling the information to create an unflinching, quantitative analysis that examined medical errors from a unique perspective. Associate managing editor Robert Blau, who oversees projects, and deputy project editor George Papajohn meticulously dissected my methodology of computer analysis—an essential component of the vetting process. Each case was built blank by blank—spreadsheet cell by cell—with the goal of assembling an incontrovertible story that detailed the issues to the number and to the person.

The computer provides reporters access to information that can’t be seen in any other way. Increasingly, public information is stored exclusively in computers. Those who don’t know how to enter these electronic vaults remain modern-day illiterates. Would anyone hire a reporter who refused to use the telephone? Yet, in the early days of this groundbreaking technology, there were undoubtedly those who argued that face to face information gathering was the only proper way to do the job.

Fundamental reporting skills are still essential. A computer will not make a bad reporter good. But the computer empowers journalists to go beyond the press release. Few interview techniques are more potent or fruitful than confronting officials with computer analysis of their data.

This proved true during the first weeks of my research. The project began with little more than a realization that the nation’s 2.6 million registered nurses comprised the nation’s largest healthcare profession. For my first interviews, nurses emphatically warned me that unprecedented staffing cutbacks were endangering hospital patients. However, the American Hospital Association (AHA) maintained that a record number of registered nurses were employed by hospitals, a position bolstered by a Bible-sized book of statistics.

Using the association’s published data, I entered it into a spreadsheet program, then I cross-matched these totals with information about staffing levels that I gleaned from nurse union contracts and Medicaid cost reports. Each year, hospitals file these cost reports with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. My analysis clearly showed that fewer nurses were assigned to patient care. My conclusion: The AHA data was misleading and flawed.

When presented with my findings, an AHA spokesman made a stunning admission: The statistics included registered nurses who didn’t provide care to hospital patients. These nurses were either desk-bound or were assigned to remote nursing homes and home health agencies. In fact, the AHA didn’t ask hospitals how many nurses were assigned to patient care. This meant that the AHA’s staffing statistics created a public smokescreen.

Public response to the series was swift and overwhelming, flooding Tribune voice mail and e-mail systems. Thousands of nurses across the country continue to weigh in with compliments and criticisms. In response to many issues raised in the series, an Illinois task force is investigating staffing trends and disciplinary issues. Also, following the series, Food and Drug Administration officials acknowledged that the Tribune analysis of its databases uncovered new cases linked to nursing errors and inadequate staffing or training, proving that more patients had died preventable deaths than had been publicly acknowledged. A FDA official said, “You found things we don’t know about. We’d like to see your data.”

With the aid of computer analysis—built on electronic data, paper records and interviews—the Tribune series took readers beyond the official explanation and into a disturbing, hidden part of the health care industry where patient care is all too often measured by dollars.

Registered Nurse Janet Dotson readies the crib for a newborn at Rush-Copley Medical Center in Aurora, Illinois. The Department of Professional Regulation charged her with gross negligence resulting in the death of a patient, when Dodson worked for a temporary agency. Photo by Stephanie Sinclair, Chicago Tribune.

Mike Berens is a Chicago Tribune reporter on the project team.