Not long ago, I published a post on the MoMA website announcing the acquisition in the museum's collection of the first 14 video games. I tweeted it and then went about my business. The post has received some 200 comments and my words have been retweeted 500+ times.

My colleagues and I knew that MoMA anointing video games would provoke a stir. We had been using peculiar criteria to appreciate video games not as popular and historical artifacts or as animation and illustration masterpieces, but rather as interaction design, a fairly obscure new discipline concerning the communication between humans and machines.

In the name of interaction design, we had left out some enormously successful titles, and we were aware of how touchy avid gamers can be when you pass on their favs. Also, we expected that several embarrassingly out of touch individuals—I could bet you, some card-carrying critics among them—would thunder against the heresy of considering video games Art. We were expecting pushback, gratuitous criticism, and a good dose of snark. We were pleasantly surprised instead by the constructive debate.

Writing in Wired.com, graphic designer and author John Maeda heroically stood up for us in the face of a diatribe from the Guardian's art critic Jonathan Jones. Maeda's post was followed shortly by a rebuff from the Guardian itself, in the person of Keith Stuart, a journalist covering the videogame industry. Curators—like artists, directors, and choreographers—receive critics' valiant efforts to make the world a better place, even though they often feel the world might be better without certain curators, artists, directors and choreographers. It is easy to think of some critics as birds of prey who gratuitously undercut the creative efforts of others. Some of them feel their official role is to thunder, and they sometimes get so boxed in inside their prisons of negativity and personal taste that they become caricatures rather than critics.

There is, however, great respect for those critics who have the courage to make themselves vulnerable, as some do when they go out on a limb for what they believe. That is when they become creative authors themselves.

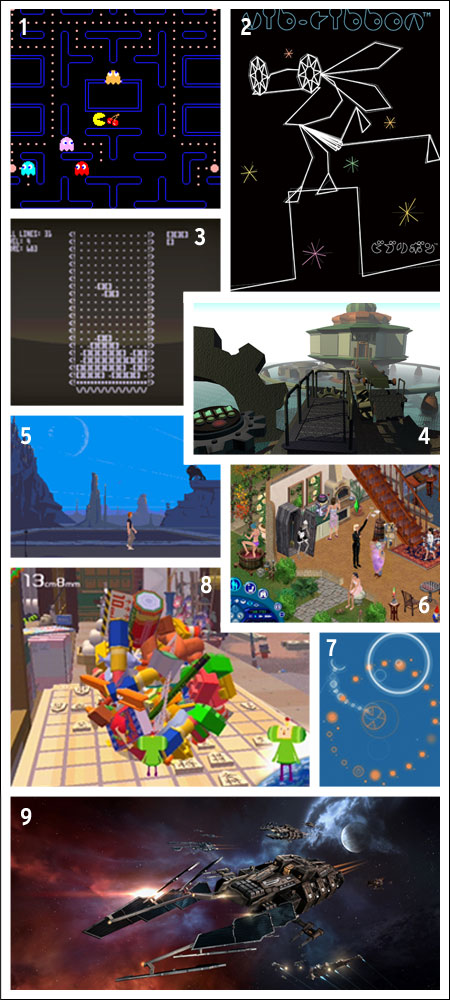

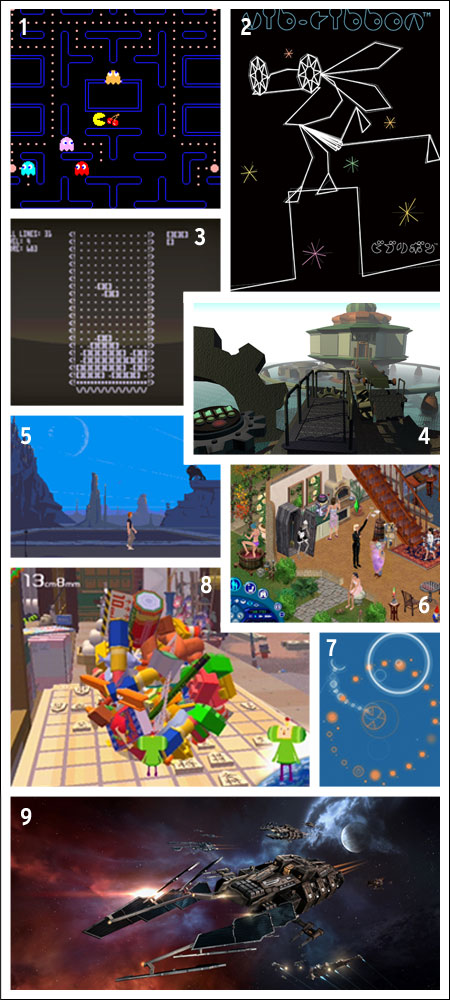

A selection of video games acquired by the Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Architecture and Design. 1. Pac-Man; 2. vib-ribbon; 3. Tetris; 4. Myst; 5. Another World; 6. The Sims; 7. flOw; 8. Katamari Damacy; 9. EVE Online. Photos courtesy of MoMA.

We consider it our duty as design curators in a major museum of modern art to render the connection between art and life through design by selecting and displaying the best possible examples. To do that, we clearly had to expand our typological categories to include, for instance, typefaces, interfaces, Web design, film titles and, yes, even video games.

In the catalogue of a 2008 exhibition about design and science, “Design and the Elastic Mind,” I wrote "designers stand between revolutions and everyday life … [They] have the ability to grasp momentous changes in technology, science, and social mores, and to convert them into objects and ideas that people can actually understand and use." Museums are providers of functional theory. Museums that tackle design, in particular, exist to preserve selected objects that together will build a consistent ensemble and support and communicate a strong idea. Exemplary objects are the tools that these museums use to educate the public and thus stimulate progress.

Ettore Sottsass, the great architect and designer, saw design as a way to discuss life: "It is a way of discussing society, politics, eroticism, food and even design. At the end, it is a way of building up a possible figurative utopia or metaphor about life." Since design in all its forms has a tremendous impact on everybody's life, and a better understanding of it will undoubtedly work to everybody's advantage, an art museum with a design collection becomes a very powerful cultural and social agent.

In this light, it is important for curators, whether they study contemporary or historical design, to be very aware of the culture within which they operate. The same is true for critics, if they really want their work to point out new, worthwhile directions, to sharpen the audience's critical tools.

Design is about people and life. It thrives on change and, as such, it is in continuous mutation. Collections are instead permanent records, or at least they used to be. Contemporary curators, however, feel compelled to reflect their time and therefore design collections that are open, their essence self-assured enough to embrace change and pluralism.

We want our practice to change as well, and we would like our museums' collections to include multimedia design and information architecture, interfaces and biomimicry, as well as examples of experimental design that project the consequences of new technologies. I personally also dream of expanding our reach even wider and celebrate even food and scents as forms of design. Our trouble, if anything, is to know when and where to stop.

We've moved relatively quickly to realize this vision. We acquired several interfaces, starting with John Maeda's 1994 Reactive Books, as well as examples of visualization design, celebrating the work of Ben Fry and Martin Wattenberg and Fernanda Viégas, among others. We have acquired 23 digital fonts and our first film title sequence, by Robert Brownjohn for Goldfinger. We also experimented with what I hope will be the first of several "impossible" acquisitions, one of which I am particularly proud: the @ sign. The @ sign crystallizes an astonishing number of the positive attributes we seek in contemporary design. If our job as curators is to present a list of objects that support an idea, we will go to any length to do so, even if these objects cannot be possessed because they are in the public domain.

The comments on our video games acquisition keep coming. We expect a second wave of discussion with the opening of the new installation of the Architecture and Design galleries featuring them. The games will be deliberately mixed with other design objects—from visualizations to furniture and safety equipment—in an exhibition entitled "Applied Design" (March 2-January 31, 2014) that highlights the extraordinary diversity and range of contemporary practice.

We are testing something new, exposing new ideas to criticism and scrutiny, trying to move us all a bit towards a deeper public understanding of design through great examples. In other words, we—curators and critics alike—are doing what we think is our job.

Paola Antonelli is senior curator in MoMA's Department of Architecture and Design.

Paola Antonelli is senior curator in MoMA's Department of Architecture and Design.

My colleagues and I knew that MoMA anointing video games would provoke a stir. We had been using peculiar criteria to appreciate video games not as popular and historical artifacts or as animation and illustration masterpieces, but rather as interaction design, a fairly obscure new discipline concerning the communication between humans and machines.

In the name of interaction design, we had left out some enormously successful titles, and we were aware of how touchy avid gamers can be when you pass on their favs. Also, we expected that several embarrassingly out of touch individuals—I could bet you, some card-carrying critics among them—would thunder against the heresy of considering video games Art. We were expecting pushback, gratuitous criticism, and a good dose of snark. We were pleasantly surprised instead by the constructive debate.

Writing in Wired.com, graphic designer and author John Maeda heroically stood up for us in the face of a diatribe from the Guardian's art critic Jonathan Jones. Maeda's post was followed shortly by a rebuff from the Guardian itself, in the person of Keith Stuart, a journalist covering the videogame industry. Curators—like artists, directors, and choreographers—receive critics' valiant efforts to make the world a better place, even though they often feel the world might be better without certain curators, artists, directors and choreographers. It is easy to think of some critics as birds of prey who gratuitously undercut the creative efforts of others. Some of them feel their official role is to thunder, and they sometimes get so boxed in inside their prisons of negativity and personal taste that they become caricatures rather than critics.

There is, however, great respect for those critics who have the courage to make themselves vulnerable, as some do when they go out on a limb for what they believe. That is when they become creative authors themselves.

A selection of video games acquired by the Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Architecture and Design. 1. Pac-Man; 2. vib-ribbon; 3. Tetris; 4. Myst; 5. Another World; 6. The Sims; 7. flOw; 8. Katamari Damacy; 9. EVE Online. Photos courtesy of MoMA.

We consider it our duty as design curators in a major museum of modern art to render the connection between art and life through design by selecting and displaying the best possible examples. To do that, we clearly had to expand our typological categories to include, for instance, typefaces, interfaces, Web design, film titles and, yes, even video games.

In the catalogue of a 2008 exhibition about design and science, “Design and the Elastic Mind,” I wrote "designers stand between revolutions and everyday life … [They] have the ability to grasp momentous changes in technology, science, and social mores, and to convert them into objects and ideas that people can actually understand and use." Museums are providers of functional theory. Museums that tackle design, in particular, exist to preserve selected objects that together will build a consistent ensemble and support and communicate a strong idea. Exemplary objects are the tools that these museums use to educate the public and thus stimulate progress.

Ettore Sottsass, the great architect and designer, saw design as a way to discuss life: "It is a way of discussing society, politics, eroticism, food and even design. At the end, it is a way of building up a possible figurative utopia or metaphor about life." Since design in all its forms has a tremendous impact on everybody's life, and a better understanding of it will undoubtedly work to everybody's advantage, an art museum with a design collection becomes a very powerful cultural and social agent.

In this light, it is important for curators, whether they study contemporary or historical design, to be very aware of the culture within which they operate. The same is true for critics, if they really want their work to point out new, worthwhile directions, to sharpen the audience's critical tools.

Design is about people and life. It thrives on change and, as such, it is in continuous mutation. Collections are instead permanent records, or at least they used to be. Contemporary curators, however, feel compelled to reflect their time and therefore design collections that are open, their essence self-assured enough to embrace change and pluralism.

We want our practice to change as well, and we would like our museums' collections to include multimedia design and information architecture, interfaces and biomimicry, as well as examples of experimental design that project the consequences of new technologies. I personally also dream of expanding our reach even wider and celebrate even food and scents as forms of design. Our trouble, if anything, is to know when and where to stop.

We've moved relatively quickly to realize this vision. We acquired several interfaces, starting with John Maeda's 1994 Reactive Books, as well as examples of visualization design, celebrating the work of Ben Fry and Martin Wattenberg and Fernanda Viégas, among others. We have acquired 23 digital fonts and our first film title sequence, by Robert Brownjohn for Goldfinger. We also experimented with what I hope will be the first of several "impossible" acquisitions, one of which I am particularly proud: the @ sign. The @ sign crystallizes an astonishing number of the positive attributes we seek in contemporary design. If our job as curators is to present a list of objects that support an idea, we will go to any length to do so, even if these objects cannot be possessed because they are in the public domain.

The comments on our video games acquisition keep coming. We expect a second wave of discussion with the opening of the new installation of the Architecture and Design galleries featuring them. The games will be deliberately mixed with other design objects—from visualizations to furniture and safety equipment—in an exhibition entitled "Applied Design" (March 2-January 31, 2014) that highlights the extraordinary diversity and range of contemporary practice.

We are testing something new, exposing new ideas to criticism and scrutiny, trying to move us all a bit towards a deeper public understanding of design through great examples. In other words, we—curators and critics alike—are doing what we think is our job.

Paola Antonelli is senior curator in MoMA's Department of Architecture and Design.

Paola Antonelli is senior curator in MoMA's Department of Architecture and Design.