When I was hosting my political satire show, “Al-Bernameg” (“The Program”), on Egyptian TV, I thought that making jokes made you immune to the risks many in the media faced. The Charlie Hebdo killings proved me wrong.

We would like to tell ourselves that accepting satire is a sign of progress. But the truth is, even free societies don’t always celebrate free speech.

In 1962, Chicago police arrested Lenny Bruce on obscenity charges for his stand-up act. He was found guilty of violating state obscenity laws, a verdict that was reversed by the Illinois Supreme Court. A decade later, in Milwaukee, George Carlin was arrested for his now iconic “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television.” The obscenity charges against him were dismissed, but the battle over his “Seven Words” monologue went to the U.S. Supreme Court. FCC v. Pacifica Foundation established the federal government’s authority to regulate the broadcast of “indecent” speech.

The persecution of satirists, directly by governments or indirectly through public pressure and workplace intolerance, has a long history. In “The Offensive Art: Political Satire and its Censorship around the World from Beerbohm to Borat,” Leonard Freedman details how, during World War I, Robert Minor, who drew anti-war cartoons for the New York Herald, was fired when the paper began supporting the war. After World War II newspaper editors dropped Bill Mauldin’s syndicated cartoon over his criticism of postwar America. Mauldin’s syndicate, responding to a wave of canceled subscriptions, censored and altered parts of his work—covering up a swastika in a cartoon that compared Congress’ anti-communist investigations to fascism, for example—before parting ways with him. Bill Maher, the host of HBO’s “Real Time,” lost his show “Politically Incorrect” in 2002 after sparking controversy by making comments about the 9/11 attacks some interpreted as anti-U.S.

We would like to think that violations of free speech belong to a different and distant era. But after the Charlie Hebdo attacks, French police arrested comedian Dieudonné on charges of condoning terrorism because of a Facebook post interpreted as expressing sympathy for the terrorists. Dieudonné was the most prominent of at least 54 people arrested in France on the Wednesday following the attacks. He was found guilty in March. The question of whether the comments of Bruce, Carlin, and Dieudonné are free speech, hate speech, or just bad taste has been and will continue to be answered according to which side of the joke you find yourself on. But it is always healthy to have this kind of a debate.

Western countries aren’t the only ones being selective about what constitutes free speech. Muslims do their fair share of picking and choosing, too. As a Muslim, I have seen people of my faith become angry about cartoons they consider insulting to our prophet and our religion. However, these same people don’t become angry when other Muslims seriously tarnish our religion through their actions—ISIS, Boko Haram, Al Qaeda, and many other lunatics whose actions are not worthy of belonging to any part of human history, not even the Dark Ages.

For me, satire should be directed at the two biggest authorities: the people in power and the people in media. There is absolutely no courage or chivalry in mocking people who cannot answer back. As poetic as it is to think that satire can topple governments and change regimes, it can’t do this. All it does is bring more people to the table. Whether change happens is up to the people, not the satirists.

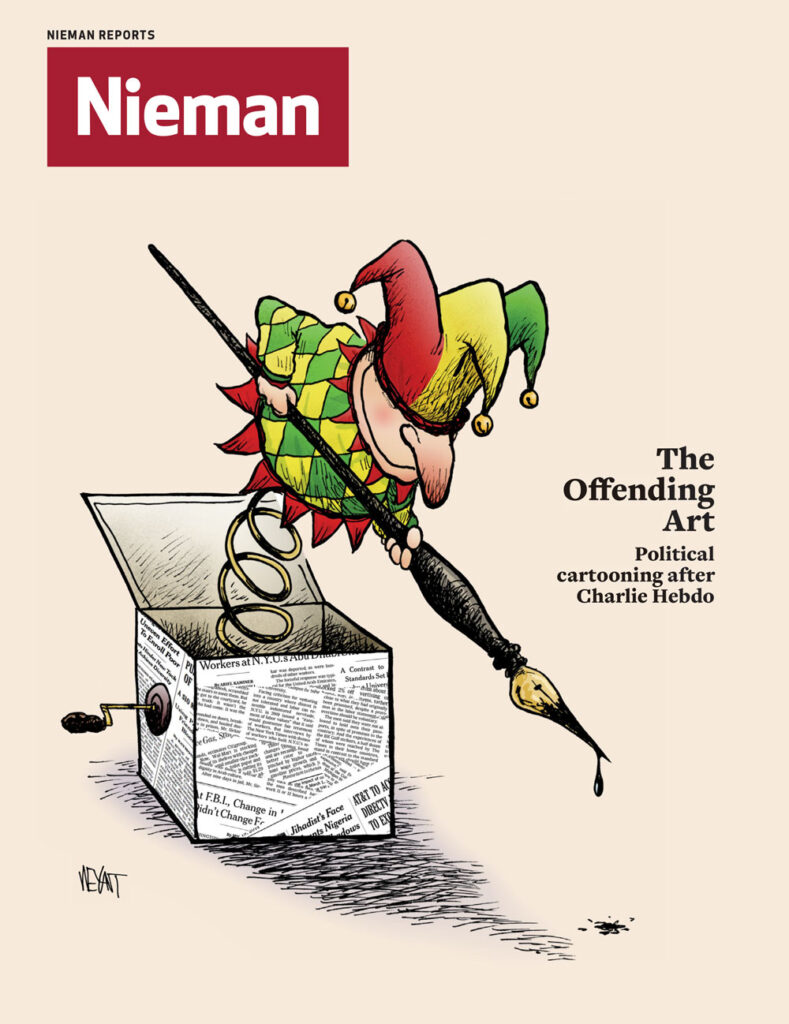

Satire is an offending art. There will always be satirists who break taboos and make jokes that hurt and offend us and make us uncomfortable. You push the limits, but you have to be careful not to alienate people from your cause.

And there will always be people who, in the name of some higher power—God, national security, freedom—will try to decide for us what should be accepted as free speech, even as they themselves violate the teachings of God, the pillars of national security, and the tenets of freedom. They forget that those who try to tame satire always end up being the biggest source of material for satirists.

Satire will never cease, not because humans are so creative, or because freedom will finally prevail, but because humans themselves are one big joke.