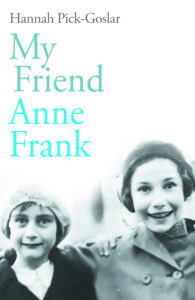

For Dina Kraft, NF ’12, writing Hannah Pick-Goslar’s story was a chance to keep her memory alive

When I started helping Hannah Pick-Goslar, one of Anne Frank’s best friends, write her memoir earlier this year, I knew we were in a race against time. Still razor sharp of mind, but increasingly frail of body at 93, she’d get tired after a couple of hours of talking. I’d say, “That’s fine, we can break for today.” But then she’d inevitably think of another thread, another story and I’d settle in and keep recording.

Hannah died in late October at her Jerusalem home, six months after we met for our first interview for the memoir. I was extremely fortunate to have had the time to not only learn the details of her life story directly, but to get to know her as the remarkable, resilient person she was. At 16 she kept her four-year-old sister alive as the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp descended into chaos in the final months of the war when typhus swept the camp and prisoners were left to starve to death.

It was during this time, on a cold, rainy night in February 1945, that Hannah and Anne Frank had a chance encounter in Bergen-Belsen across a barbed wire fence. Hannah was stunned Anne was there, she had been the first of their friends to discover the Frank family had left their apartment in July 1942 and had believed their cover story — that they had escaped to Switzerland. Hannah found a shell of her once vivacious friend at the fence. Anne was now freezing and starving, and her sister Margot was already weak from typhus, the disease that a few weeks later would kill them both. Risking her life, Hannah would return twice to throw small packages of food over the fence to Anne, the first of which was snatched away by a fellow prisoner.

I first met Hannah in 1998 when I interviewed her for the Associated Press about a biography that had been recently published about her. I had been so excited to meet her, remembering her as Anne Frank’s friend “Lies” in the diary which I had read when I was 13. About 24 years later, in January, a literary agent contacted by Penguin Random House in London approached me about ghostwriting a memoir of a Holocaust survivor. The book project — titled “My Friend Anne Frank” — was off the ground after I submitted writing samples and met with Hannah. I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to get to know Hannah and through our daily interviews over cups of tea, to also find a new friend in her.

The task of co-writing Hannah’s memoir is a life-changing responsibility. Every day we lose more eyewitness to the cruelty and carnage of the Holocaust. I’m humbled by the opportunity to help keep her story alive in the world, especially now, when unfortunately, it feels more urgent than ever.