Voyages of Discovery Into New Media

At the crossroad of old journalism and new media, digital news entrepreneurs lead us on voyages of discovery into new media. From MinnPost to MediaStorm, these entities are using visual media, interactivity and social media to watchdog government abuse and the justice system, identify environmental dangers, and tell enduring stories. In doing so, they illuminate possibilities.

It is a journalistic paradox. Newspapers and other media are shedding reporters and editors by the thousands, with worrisome ramifications: The press watchdog, so essential to a functioning democracy, doesn’t bark as much or as often. Yet despite the newsroom carnage, journalism schools are brimming with fledgling reporters convinced that career opportunities in the news business are boundless.

In those crosscurrents, there is opportunity for collaboration in almost any city with a newspaper and a college or university journalism program. For news organizations that can no longer afford to do much enterprise and investigative reporting, journalism students eager for experience—and bylines—can help fill the void. And their work can be overseen by journalism professors who most often have substantial news credentials.

At Northeastern University in Boston, where I joined the faculty in 2007, students in my investigative reporting seminars have produced 11 Page One stories for The Boston Globe in just 20 months. What’s more, the university’s School of Journalism has started a regionwide First Amendment Center to fight for public records for news organizations that no longer have the money to wage those battles.

This enterprise, however, is not for the academic faint-of-heart or for risk-averse local editors. But the potential rewards are well worth the effort: students learn reporting techniques that will help make them valuable postgraduate hires; newspapers find the extra reporting firepower a godsend. And there is a payoff, too, for a public justifiably concerned about what the loss of in-depth reporting in so many newsrooms might mean for them.

My graduate and undergraduate students try to outdo one another with their doggedness. In two successive semesters, students spent weeks poring through voluminous records in county courthouses as part of two separate investigations of the commonwealth’s court system. One of those articles prompted reforms to protect the rights of the elderly. The second story forced the courts to change the way they treat adults who are developmentally disabled.

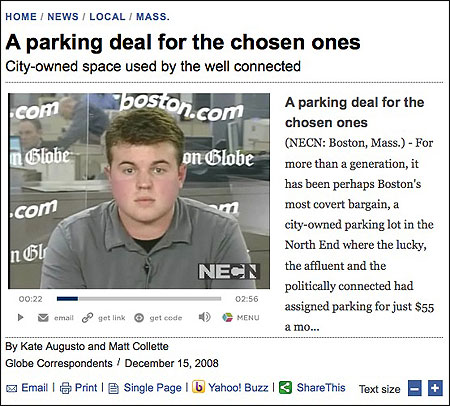

Last year, weeks of database reporting by two graduate students resulted in the exposure of a disability pension scam involving more than 100 Boston firefighters; those articles prompted an ongoing federal grand jury investigation. In another seminar, four students produced an exhaustive Sunday article about many Boston high-end restaurants that had been cited for serious health code violations by city officials who chose to keep the results private.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Digging Through Data and Discovering a Profitable Handshake"

- Marcella Bombardieri and Scott AllenThis Northeastern University–Boston Globe collaboration was not born of necessity. Although the Globe has made substantial staff cuts, Editor Martin Baron remains deeply committed to investigative reporting. Globe reporters routinely dig out important stories. And the investigative unit, the Spotlight Team, has not been affected by staff reductions. When I was assistant managing editor for investigations at the Globe and worked for Marty, I ran the Spotlight Team. I left the paper after 34 years to teach investigative reporting, but I didn’t want my students learning in a laboratory. Marty quickly realized the potential of a partnership. So, too, did Stephen D. Burgard, the director of Northeastern University’s School of Journalism.

RELATED WEB LINK

The Citizen Journalist's Guide to Open Government

Provided by the Knight Citizen News Network, this online resource helps citizens and journalists gain access to government records.In Boston, there are so many investigative story prospects that even a standard-issue class assignment can bear fruit. One such assignment requires students to do soup-to-nuts public records scrubs on public figures to acquaint them with the myriad public records that can be plumbed for just about any story. Last year, in delving through those records, two students turned up a pattern of questionable business dealings by a top fundraiser for Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick. The governor, the Globe subsequently reported, abruptly jettisoned the fundraiser when the Globe asked about the business dealings.

The university’s New England First Amendment Center, formed in collaboration with a group of New England editors, is still in its formative stages. We have a Web site—http://neu.edu/firstamendment—that updates news on public records and open meeting law issues. The center also hosts a hotline to help reporters fight for access to public records that make for important watchdog journalism. Few newspapers, however, can afford to go to court to force the issue of obtaining critical public documents when access to them has been blocked. So our center has enlisted help from students at Northeastern University’s School of Law. They’ve written the briefs. And with pro bono help from a First Amendment lawyer, we’ve filed our first lawsuit on behalf of a midsized Massachusetts newspaper.

Our modest start at Northeastern can be replicated by any adventurous journalism program. Journalism teachers need not limit themselves to wringing their hands at the plight of the news business. Nor should students need to wait for newsroom internships or graduation to do reporting that gets published in a metro newspaper—reporting that makes a difference. And savvy newspaper editors ought to welcome the help.

Walter V. Robinson is Distinguished Professor of Journalism at Northeastern University. For 34 years he was a reporter and editor at The Boston Globe. In 2003, he and his Spotlight Team reporters won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for the Globe’s coverage of the clergy sexual abuse scandal.