Voyages of Discovery Into New Media

At the crossroad of old journalism and new media, digital news entrepreneurs lead us on voyages of discovery into new media. From MinnPost to MediaStorm, these entities are using visual media, interactivity and social media to watchdog government abuse and the justice system, identify environmental dangers, and tell enduring stories. In doing so, they illuminate possibilities.

Anyone who spent much time in the medical community in Boston heard the grumbling: that Partners HealthCare—parent company of Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital—was the richest, the biggest, and the most eager to corner the market in every part of greater Boston. To those of us who covered medical issues at The Boston Globe, the whispers seemed, frankly, a little whiny. The Brigham and the General were two of the most prestigious hospitals in the world, their trauma centers ready to accept victims of any tragedy, their researchers churning out important discoveries.

Then, a little over a year ago, the Globe’s Spotlight investigative team embarked on a project with the goal of finding out why Massachusetts has the most expensive health care in the United States. In part, this project was spurred by the establishment of the state’s universal insurance program in 2006—regarded as a possible model for national health care reform. Its success was going to rise or fall on the state’s ability to curtail the growth of medical costs.

Our reporting and editing team ranged from four to six people at various times, and we began our investigation by educating ourselves thoroughly in health care finance. We canvassed experts, vacuumed up studies, and plumbed the depths of consolidated financial statements, all the while keeping in mind that we needed to find a way to tell this financial story to readers who would not want to feel buried in the minutia of spreadsheets. For example, one approach we considered was to focus on the absurdity of a medical arms race that seems to put an MRI machine on virtually every corner.

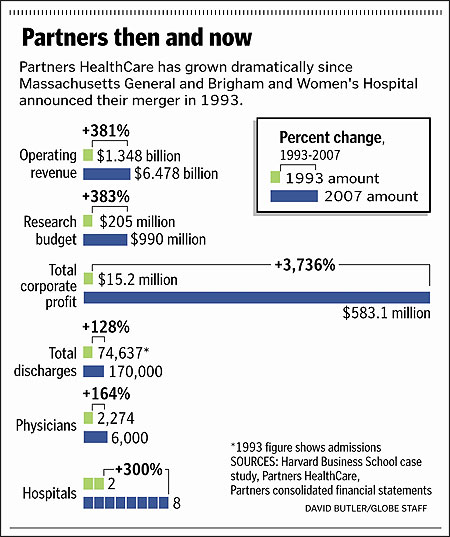

Yet the road kept leading us back to Partners, a chain of eight hospitals (with Massachusetts General and Brigham being the largest) and 6,000 doctors, which is the biggest private employer in the state. As we talked with sources, several people who had a range of different vantage points on the overall health care industry told us, though rarely on the record, that Partners is paid more by insurers than comparable hospitals in the same city and region. With this additional money, Partners, we were told, plows its extra cash into expansion projects that, in turn, add to the cost of health care and threaten to destabilize smaller hospitals.

Perhaps those disgruntled whisperers had a point.

Deciphering Data

With the luxury of time that our Spotlight Team is fortunate to have, and our own willingness to train ourselves in health policy nuance, we were able to push past the usual defenses Partners successfully put forward to deflect past critiques. When asked about its market share, Partners’ customary response is 22 percent. But that figure only holds up when the market is defined as all of eastern Massachusetts; when we focus on Partners’ primary market, the four counties in and around Boston, and include hospitals that are not owned by Partners but are staffed by Partners- affiliate doctors, the company controls 37 percent of patient discharges. Partners also typically claims that its profits are a small fraction of other well-known hospitals. Yes, their profit margin is low, but that’s because they deliberately keep it that way by using the rest of their surplus—up to one billion dollars a year—to expand.

As we dug into reporting on Partners, our biggest obstacle was not having the data we’d need to show how much Partners is paid relative to other hospital companies. The rates insurance companies pay hospitals for everything from 15-minute office visits to brain surgery has been held as a trade secret for decades. We wouldn’t have launched this project if we didn’t have some reason to believe we could obtain the information from confidential sources. But, once launched, this turned out to be much harder than we’d thought. Instead of the weeks we’d hoped for, it took us months of cajoling sources—and during those months, our team had nightmares about what we’d do if we weren’t able to secure this data.

Ultimately, we obtained a rich database that had been assembled, but not yet published, by a Massachusetts agency created under health care reform. With this data, we were able to document the astonishing differences in payments made to Partners compared with other nearby hospitals and doctors. Partners’ flagships, the Brigham and Massachusetts General, are paid on average 30 percent more than similar teaching hospitals and as much as 60 percent more than community hospitals.

Eye-popping as these figures were, for our storytelling purposes the numbers could not stand on their own. Grateful patients and their doctors at Partners had the same instinctive response when we showed them the numbers: Isn’t the care just better at Partners?

Often, the answer turns out to be no, particularly for the ordinary procedures that make up the bulk of hospital business. Our timing was fortunate, because it would have been impossible to document this only a few years ago. We benefited from the burgeoning of a transparency movement in which government and private groups have pushed data about hospital performance into the open and onto the Internet. The federal government has a Web site called Hospital Compare that scores hospitals on how often they meet routine standards, such as giving aspirin to a heart attack patient. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts also gives hospitals mortality scores for everything from hip replacements to coronary bypass surgery.

Because some hospitals see sicker patients than others, capturing which is really doing a better job is very difficult, and all of these methods of quantifying and comparing are controversial and imperfect. So we consulted experts on quality measurement from academia, government and the medical and insurance industries, and they helped us to settle on ways to use the data that were cautious and fair but also added value to the chaotic jumble of numbers found on different Web sites.

One method we chose was to assemble 42 mortality scores from several sources covering a six-year period, then average scores and group hospitals into five statistical tiers. Turned out that neither Brigham nor Mass General made it into the top category; Brigham was in the second highest group and Mass General in the broad middle.

Crunching the data was crucial to nail down our conclusions, but our goal was not to publish our own hospital guide. So we devoted only a few paragraphs to such numerical analysis and mostly let it infuse the larger tale. These findings backed up what we’d been hearing from many respected health care quality experts; in general, expensive teaching hospitals are not better than community hospitals for routine care and, more specifically, routine care at the Brigham and Mass General tends to be good, but not extraordinary. It makes sense to treasure teaching hospitals for their sophisticated trauma centers and brilliant surgeons, but 85 percent of what these hospitals and doctors do is routine medicine such as delivering babies and repairing hernias.

Exposing a Costly Arrangement

Our project depended on experts who were willing to spend hours explaining the intricacies of hospital billing, contract negotiations, accounting practices, and health care statistics. Along the way, some ended up giving us old-fashioned news scoops, including leads to what would be one of the more incendiary revelations to come out of our investigation.

According to officials directly involved in the talks, Partners and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, the state’s dominant insurer, made a pact in 2000 in which Blue Cross gave Partners a much higher rate increase than it otherwise would have in exchange for Partners’ promise to demand equally high payments from other insurers. Since then, health care costs in Massachusetts have grown at twice the pace they did in the late 1990’s, and Blue Cross has increased its payments to Partners by 75 percent. Partners and Blue Cross both say they did nothing improper and that hospital rates had been too low.

This handshake deal—never put in writing for fear of legal ramifications, according to our sources—is now under investigation by the Commonwealth’s attorney general. And publication of our story about this deal and its ramifications in December 2008 prompted Governor Deval Patrick to convene meetings of senior administration officials and health industry leaders to discuss how to contain costs. He also threatened new regulation to block excessive insurance premiums.

Understanding this incredibly complex industry required that we learn how to use the lingo of business, law, politics and medicine all at once. It also required a willingness on our part to accept shades of gray in characterizing what has happened. Partners, after all, employs thousands of devoted and skilled clinicians, and its outsized power is to some extent the fault of lax government oversight and rivals who failed to compete effectively.

The back-and-forth we’ve had with Partners has been particularly intense. Partners’ leaders are some of the country’s top medical and managerial talent. They have a deep wallet to pay political operatives, public relations consultants, and policy analysts who churn out PowerPoint presentations challenging what we’ve reported. They’ve tried to convince us on numerous occasions that we simply don’t understand; sometimes they employ obvious putdowns such as, “I don’t know how many statistics classes you’ve taken, but ….” They’ve run numerous full-page ads in the Globe, complained to our editor and publisher, and posted detailed critiques of our work on their Web site.

Yet, at the Globe, we continue to examine the practices of both Partners and Blue Cross. By the time we finish with this project, we will have spent at least a year working on it and published five or six major pieces. The slow pace of this complicated work has been frustrating, but the willingness of our editors and publisher to make this investment has been a great gift.

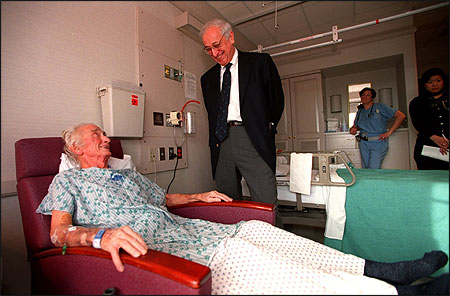

Dr. Samuel O. Thier, former CEO of Partners HealthCare, visited a patient during rounds. He led the company’s successful effort to demand higher payments from insurance companies, which he believed were severely underpaying hospitals. Photo by Pam Berry/The Boston Globe.

Marcella Bombardieri, who previously covered higher education, and Scott Allen, who has covered medicine as a reporter and editor for a decade, are members of The Boston Globe’s Spotlight Team.