RELATED ARTICLE

“Cynicism and Skepticism”

– Phil Trounstine Policy as a Character Issue

Paul Taylor, former reporter, The Washington PostBefore many reporters were out on the presidential campaign trail, the Committee of Concerned Journalists (CCJ) gathered some of the nation’s top political journalists to talk about campaign coverage. Out of these conversations emerged approaches that offer reporters ideas about how to improve what they do and expand the breadth of their coverage. As the CCJ writes on its Web site (www.journalism.org) as it introduces this toolbox of ideas, “… in an age of political alienation and declining voter turnout, journalists need to examine whether the conventional ways of doing the job are adequate.” What follows are some suggestions made by these political reporters and compiled by CCJ.

Ruts, Traps and Thinking Outside the Box

In the day-to-day of campaign coverage it is easy to lapse into oversimplifying the issues and people. Campaigns become games that we know so well we begin to think we know the answer to every question. And we write about it that way. Below are some ways of avoiding the kind of coverage that comes with over-familiarity.

- Examine Our Most Cynical Assumptions

Phil Trounstine, former political editor, San Jose Mercury NewsThere is a difference between being skeptical and being cynical. The skeptic has an open mind; he or she is unsure and wants to take into account all possible answers to a question in order to be sure. The cynic has a closed mind; he or she assumes they already know the answer—and often it is the worst. In the day-to-day of coverage it is easy to get locked into a view of politicians as being “corrupt” in some way—pandering to voters, to big business, to big donors. But part of being skeptical is being skeptical of your own thoughts and biases and considering other interpretations of the action. It’s quite possible, for instance, for a politician to take a position because he really believes it, then receive mone from lobbying interests for doing so, and to please his constituents at the same time. That is, actually, how the political system was designed to work. All three things can coexist at the same time. Just because the politician profits from doing this does not necessarily mean that profit is his only motivation. Various journalists told us: Review your stories for cynicism. Most often, taking the cynical view may make you feel like a hard-bitten realist, but it may actually be simplistic. Read Trounstine’s thoughts on cynicism versus skepticism.

- Policy as a Character Issue

Paul Taylor, former reporter, The Washington PostSee policy and platform as a frame to understand character. More important, and more useful, than just what position a person has on an issue, is what that position says about someone. How did they come to this position? Why do they feel this way? Have their views changed? How steadfast are they on it? How extreme or moderate? How does it differ or reinforce other positions on other issues? How does it fit into the history of thinking in their party on that issue? How does it fit into their worldview? What experiences or what in their biography led them to this? Suddenly, policy and issues come to life, become people stories and take on an authenticity that they lack in the abstract. This approach may also be the key to unlocking whether a candidate really means something or whether he or she just adopted a position for an electoral purpose or to satisfy a constituency or lobbying interest.

- Find the Invisible Campaign

Bill Kovach, CCJ chairmanTalking to voters is a way to find out what will decide the election, but who is talking to them and how? Are we missing the story because campaigning has disappeared into the private sphere, with candidates increasingly making appeals via direct mail, e-mail, CD-ROM, etc.? Reporters might want to troll the Internet during the campaign, not just to write a “technology and the campaign” story, but to find out what people are talking about. Reporters might want to register with different campaign Web sites and find out what kinds of messages they get. They could check with community members who have registered to see if different localities and social groups get different types of messages, or ask a group of voters to collect all the direct mail they get.

- Get Beyond Liberal/Conservative Paradigm and Look at Problems and Issues From New Angles and in Broader Terms

Bill KovachIssue coverage is about more than presenting two voices disagreeing with one another. Look at the root causes of the issues being discussed. Look at how other countries, state or municipalities handle them. Focus on possible solutions people can choose between rather than just partisan acrimony.

Using Polls and Talking to Citizens

The reporters CCJ assembled said that political reporting is often too focused on polls. They become the prism through which we journalists see everything. “Candidate X” is doing this because he’s behind in the polls. He took this position because it appeals to a voter group he is lagging with in the polls. But poll reporting turns the public into an abstraction. People and issues become numbers that have no depth and no complexity, no explanation of why people are reacting the way they are. Below are some ways to get beyond poll-centric reporting:

- Don’t Just Reprint Polls—Understand Them

National Council on Public PollsJust running numbers can miss the key points of a poll. Talk to pollsters about how best to use polls, how to read methodology, what kinds of things you should look out for in judging how well a poll was conducted, what you should disclose to the public in regards to sample size, etc. The National Council on Public Polls has put together a list of “20 Questions Journalists Should Ask About Polls.” Some of the questions on its list: Who did the poll? Who paid for the poll? How were the interviews conducted? What is the sampling error? What questions exactly were asked? The entire list of questions with explanations is on Public Agenda’s Web site.

- Don’t Treat Every Poll Like ‘News’ (Put Your Poll Coverage in Agate)

Jack Germond, former (Baltimore) Sun columnistWhen looking at poll results ask yourself if the are telling your readers anything new. Unless a given poll produces unique, interesting results the poll results might not always be the story. One way to handle the steady flow of polls that come at election time may be to create an agate box and have them there for readers to review them, á la sports box scores. This will allow readers to access the polls without having them be a defining aspect of your coverage.

- Cover the Things That Matter Most to People

Don’t just cover what the candidates want to talk about. Identify and cover what affects the most people in your community and what matters most to them. That involves, of course, having some way of identifying what those things are, which is a reporting challenge all its own. You will benefit from taking the trouble to find out.

- Talk to Voters

David Jones, The New York TimesCover voters, not polls. It is voters—what they think, how they live, what they are worried about—that are important (and also more interesting). Polls turn the public into an abstraction, reacting to questions and constructs of the pollster/journalist. But voters/citizens may have very different constructs. Ultimately, why people think what they do is more interesting than simply what they think (i.e., whether they support a certain policy or not), since their opinion (“I approve of the President”) may change. Understanding when and how will depend on the reasons for their support in the first place. Polls are only a tool to get at voters and only one tool. Relying on that one tool too much will bias your coverage. Other tools include focus groups, or panels (a recurring group of voters you visit), knocking on doors, talking to people in malls, talking to people at rallies.

- How to Knock On Doors

Paul Taylor and Jack GermondKnocking on doors may be becoming a lost art among political reporters. But here is the counsel of two old-school scribes on how to do it: Hang out with different groups of people and have informal conversations. Go to nursing homes and play checkers. Talk to union workers. Talk to people at random. Go in flat. Don’t use political jargon. Go in without an agenda. Don’t be there to find out how they respond to the appeals of the different campaigns. Ask them what’s on their minds. Let them lead the conversation. In two days, you should have 30 to 35 people who you talked to long enough to have notes on them. And, if you find you’re hearing the same thing from four or five of them, pay attention. You will know, at the end of that time, what’s going around. (In 1992, one journalist first knew George Bush was in trouble when he asked a hotel manager how business was. “Great,” was the answer. “I thought the state was in financial trouble,” the reporter said. “We’re full up with federal and state bank regulators here because of possible bank failures,” the hotel manager said. That was when the reporter knew the New England economy was in worse shape than anyone knew.)

- Stay Behind After the Campaign Leaves

Paul Friedman, former ABC News executive vice presidentOften when a candidate makes an appearance it is like the carnival coming to town. Everyone seems to be paying attention, and people are excited. But what happens when the show leaves town? It’s often worth it to stay behind and find out. Wait a day, or even just a few hours, but see what people say later, what they think, whether the campaign stop really related to the community, or whatever story strikes you. This will let you get beyond the spin and spectacle and focus on the voters.

Broaden Your Source Base

No matter how good your questions are or how well you think you understand a race, if you aren’t talking to the right people, or to enough people, there will inevitably be holes. Below are some tips on finding those people and making sure you don’t lose them once you’ve talked to them.

- How Big Is Your Rolodex, or Who’s in Your Rolodex

Marty Tolchin, New York Times correspondent, former editor of The HillThere may be people in there you only talk to once every five or six years. There should be. You need to have a complete range of voices in there to cover politics. Not just the standard party voices and academics. Do you have the political mechanics, the dreamers, the movers and shakers, the ethics cops, the religious people, the business people, the money people? If your Rolodex is light in certain areas, you should be able to identify where and make it a mission to fill it in when you can.

- Talk to the Secret Wise Folk

Jack GermondSome of the best sources for any political reporter are former elected officials who are not vested in a campaign or a debate but are able to tell you what is going on and give you a starting point. Make sure you talk to people who were very active in politics but who are now no longer in a position to speak publicly. Judges, university presidents, retired politicians, disgraced politicians, etc. These are people you cannot quote, but they know everything. They are starved for attention. Do it in person. Do it at some length. It will be a great lunch or a great dinner. They will be flattered and tell you more than you expect, especially once they know you. Imagine Bill Clinton and Bob Dole telling you everything they could off the record before the next election for President ever started.

- Get Character Sources

Jim Doyle, former Boston Globe political writer, former Army Times editorSimilar to Germond’s “Secret Wise Folks,” but this is about character in particular. These are people whose judgment you trust about other people. They were once the people who helped decide things in the smoke-filled room and who know how people, including your candidate, play the game. They are the ones whom financial people consult in deciding whom to back. They’ll tell you what they see in the soul of candidates. These are, once again, background people. They are not on the record.

Escaping the Campaign Bubble

Spending everyday covering campaign events or traveling on the bus with the other reporters can create a kind of tunnel vision about the campaign you are covering. Watching the same speech repeatedly and talking to other reporters may give you a unique perspective on the race, but at some point it can create a myopic view of the campaign. Below are some ways to break out of the campaign cocoon.

- Identify the Meta-Narratives of the Campaign

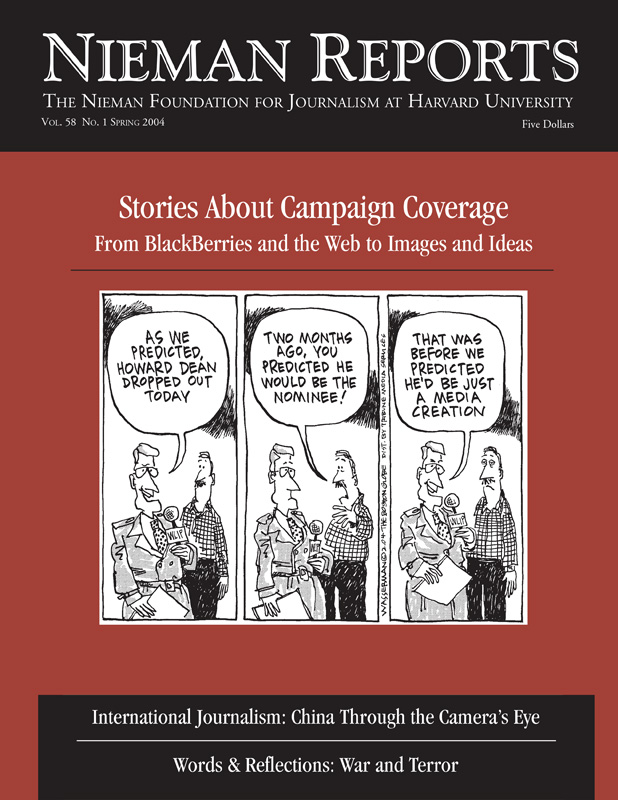

Tom Rosenstiel, director of Project for Excellence in JournalismEach campaign takes on meta-narratives, or story lines. Al Gore is a liar. George W. Bush is dumb. Jesse Ventura can’t win. Mike Dukakis is a competent technocrat. But are these meta-narratives valid? Or are they distortions? These story lines are the modern version of pack journalism, in an age when journalists spend a lot of time reading other coverage and synthesizing it. Was it true that George W. Bush is basically a pragmatist with no real ideological agenda? Sometimes, too, the meta-narratives change radically and make the press look foolish. In 1988, the early meta-narrative was that George Bush was a wimp, and Mike Dukakis was a skillful pragmatist. Months later George Bush was thought to be a manipulative campaigner and Mike Dukakis a wimp.

- Examine Your Own Biases

Paul TaylorPeriodically examine yourself for bias building up as the campaign proceeds; do not deny that you have your own views but understand what they are and why you have them in order to keep them under control. Who do you personally dislike? Why? How might that be coloring your judgment? Is your reaction to a candidate on a more personal level influencing your reporting? Who do you disagree with ideologically? Understand who you are. Do it privately. But do it seriously. Don’t pretend that your professionalism is protecting you. Don’t be in denial. “Don’t,” as Walter Lippmann once said, “confuse good intentions with good execution.” Good intentions are not enough. Create a discipline for coming to grips with your personal feelings and parking them in the back of your own head. Take stock of the total impression you have of these candidates or this race so far. Maybe even make a list of the stories you’ve done as you go through this process.

- Modesty is the Key to Good Political Reporting

Marty TolchinIf you come into anything with a preconceived attitude, whether it’s liberal or conservative or something else, you’re being lazy. It allows you to skimp on the hard work of reading and talking to people and learning everything you can about all the different ways to approach an issue. Understand that however long you’ve been covering your race or candidate, you don’t know everything. Don’t assume you know. Ask questions and report.

- Your Reporting Might Also Benefit From Another Set of Eyes

Remember that you are a very specific audience for the race you are covering. You come from a specific background and are focused intently on the issues at hand. If an ad or speech doesn’t resonate with you that doesn’t necessarily mean it is a failure. The speech or ad may not be meant for you. Run your ideas and reporting by a colleague with a different background, or ask a voter what he or she thinks.

- These Are Ordinary People You’re Covering

Jack GermondWhatever office the candidate is running for, remember that he or she is, in the end, just a regular person. Don’t be too impressed. Do not be intimidated by them. Do not treat them as different or above regular folks. Most importantly, get at the real person. Not being awed doesn’t mean treating a candidate poorly, it means treating them like a person, not a myth. It also means not cynically dismissing them.

To read CCJ’s complete campaign reporting toolbox go to www.journalism.org/resources/tools/reporting/politics/default.asp