Commemorative Double Issue

What you [see] here is a collection which reflects the substance of the first 53 years of the conversation journalists have engaged in about their rights and responsibilities in the pages of Nieman Reports. At times you will find an article that opened a new argument or ended an old one. Throughout you will hear the voices of journalists committed to their work challenging colleagues to raise the standards of discovering, reporting, writing and editing the news in a context meaningful for navigation within a free society. – Bill Kovach

A son sits by his father’s grave. The family couldn’t afford a gravestone for the 39-year-old father of three who was killed by a drunk driver. Photo courtesy of the Maine Sunday Telegram and Portland Press Herald.

[This article originally appeared in the Winter 1994 issue of Nieman Reports.]

EDITOR'S NOTE

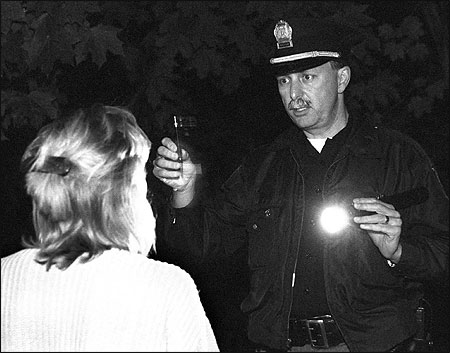

The accompanying photos, taken by David A. Rodgers, were published in a 1997 week-long series on alcohol. Reporters spent six months tabulating and profiling the cost of Maine’s alcohol abuse.What if the crisis of confidence in the media grows not out of a paranoia about whether the media leans left or right but rather out of a rejection by the public of the detachment with which the press regards the problems of society and the concerns of ordinary people?

As the discussion over the place of reporters’ viewpoints in the coverage of news heats up again, it is worth considering that what the press needs today is more context and insight, not less, and that context and insight inevitably bring with them the exercise of subjectivity. Serious and successful attempts at finding the right way to bring the perspectives of reporters into the news columns are producing an exciting and useful journalism in newspapers around the country. It is taking many forms, from the expression of studied judgments by reporters about issues to franker, more pointed sketches of public figures. There have been problems, to be sure, and they need to be understood. The challenge to the public-minded press today is to find ways to accommodate the ever present need for fair and dispassionate inquiry and the new and growing need to generate energy, meaning and solutions for the benefit of a society that has grown apathetic to civic participation.

The likelihood that the press more often fails readers through timidity than bias has led us at the Portland (Maine) Press Herald to experiment with another level of coverage in our news report, one that encourages reporters to explore wider latitudes of analysis, interpretation and judgment in the news columns. This new layer represents only a fraction of the stories we publish, and we continue to build the news report from the fundamental day-to-day coverage of events with straightforward, hard news reporting. Yet, the response from our readers to the new work has been strong and positive. Often it is where they see the value of the newspaper. It has helped us develop a newfound sense of our ability to make a difference for the better in the life of our state.

Our most recent foray into this new style of reporting sought to understand the plight of Maine fishermen who have seen their catches decline dramatically in recent years. The project, in its methods and its results, offers a good illustration of the work we are trying to achieve. The project began when a team of reporters and editors brought to the newspaper office about a dozen people who have a stake in Maine’s fishing industry: fishermen, wholesalers, federal regulators, marine scientists, and environmental activists. They were asked to talk among themselves about the state of the resource in the Gulf of Maine, once one of the richest fishing grounds in the world and now an exhausted corner of the North Atlantic. How bad was the fishery and what had caused the decline?

In minutes, the conference room where they were gathered burned with disagreement. Fishermen blamed scientists for exaggerating the depletion of fish stocks and destroying their livelihoods and communities; environmentalists blamed fishermen for taking unsustainable amounts of fish from the ocean; scientists blamed regulators for making decisions without good data, regulators blamed the government for lack of support for fisheries management.

And so it went for six hours. But for the journalists in the room the conflict they were witnessing was not the story. What use would it be to readers? The conflict was a stalemate and its only product was acrimony. For this project, conflict became a starting point, not a destination. It was the first step in an arduous process of research and understanding that culminated three months later in a five-part series that reported these conclusions:

The Gulf of Maine is commercially depleted of its most valuable fish species, and the federal government is largely to blame. Through favorable tax changes and credit incentives, the government had encouraged investors out of the region (doctors, lawyers) to form companies that built big boats that took big profits from the sea.

The depletion is so complete, and the regulatory system so stymied, that the offshore fishing industry is being wiped from the coast of Maine. To stem the disaster, the government is likely to get stuck buying back the boats it had enticed the wealthy investors to build.

Now what was remarkable about the newspaper series, beyond what it had to say about the fisheries and how the government operates, is that the reporters who were writing it refused to settle on a story about conflict and disagreement among opposition groups. They were not going to write a story that said scientists and regulators say this while fishermen and environmentalists say that. Instead, they were empowered by their editors to immerse themselves in the topic and draw their own conclusions about what had gone wrong and to share those conclusions with readers.

Like other newspapers around the country, some large and some small, the Portland Press Herald has been publishing stories in recent years that challenge traditional notions of objectivity in which fairness is achieved by quoting all parties that have standing within the circle of the issue and by keeping the text free of assessment or evaluation by the reporter. The new stories, generally in-depth pieces that go well beyond the basic enterprise story, call on reporters to submerge themselves for months in the topic and form judgments that can be expressed emphatically as conclusions about the performance of public figures, policies or institutions. These pieces state their conclusions up top without attribution from officials or authorities and rely on the body of the story to develop the evidence behind the conclusions. Often the evidence to support the conclusions comes from original research into database records and can not be attributed to an official because officials are not necessarily aware of the information.

In Portland, we usually reserve this technique for mature stories, issue-oriented stories that have had a long run in the paper, where the push and pull of debate in the daily coverage has not clarified matters for the public, and an independent and in-depth look at the topic is needed to help readers evaluate information and touch bottom on the validity of competing claims and charges. We have looked at the state’s business climate and found it to be healthy, certainly much better than described by the Maine Chamber of Commerce, which was mounting a heavy lobbying effort to roll back environmental laws. We examined a development moratorium approved by city residents to protect the Portland waterfront and found that it, instead, had hastened the disintegration of that part of the city by discouraging private investment. We looked at the decline of civic leadership in Portland and found that it was due in part to large corporations buying up local banks and businesses and replacing them with carpetbagger management.

Perhaps our greatest success came two years ago when we examined the state’s workers’ compensation system. Workers’ compensation in Maine, as in other states, was conceived as progressive legislation to protect workers against serious injury or pay them if they were injured and to protect employers against lawsuits when injuries occurred. In Maine, the law had evolved to pad the pockets of lawyers and others who could exploit the system. The law failed to protect workers from injury and death and punished businesses with huge premium costs. Attempts to reform the system repeatedly bogged down in disagreements over the extent of fraud, generosity of benefits, and statistics that described the danger of Maine’s workplaces. In 1991, state government in Maine actually came to a halt as Republicans and Democrats, surrogates for business and labor, held up the state’s budget over a workers’ comp reform effort.

In this climate of confusion and anger, a reporter for the Press Herald, Eric Blom, undertook an in-depth look at the system and wrote a powerful series of stories that contained his own conclusions, carefully reached and painstakingly tested by editors over four months. It was our first major project of this sort, and we called it expert reporting because we had asked our reporter to become an expert on the topic and draw independent conclusions based on his research. We asked him to report to readers in simple and direct language.

The series began this way:

“The Maine workers’ compensation system is a disaster. It wastes millions of dollars each year. It destroys employer-employee relationships. It distracts the state’s attention from other vital issues.”

The series went on to show Maine’s shameful rate of workplace injuries and death, the practice of blackballing injured workers, and the unreasonable costs that saddled businesses, even safe ones. It showed how expert witnesses and lawyers, some of whom were involved in writing the law, made millions of dollars from employer-employee legal battles.

The reaction from readers was quick and gratifying. They found the material understandable in its directness. The reporting created a picture of greed and confusion that rose above the contending he-said, she-said quotes of earlier stories. The series began a process that ultimately led to reform of the system, and today worker injury rates are down in Maine and costs to business are declining.

We have also made mistakes as well. We learned early on that a project that dismisses the contentions of some sources because research has shown them to be weak or irrelevant needs to explain the reasoning process that led to that judgment in the published story. Otherwise, it appears as a hole in the work, or as arrogance. It also opens the possibility that the story, rather than the topic, will become the issue.

Without question, this technique of reporting raises difficult questions for newspapers. What qualifies a reporter to undertake a project of this sort? How much time and research is needed to develop the expertise that underpins the authority of the stories? What is the role of the editor who directs the project? And perhaps most important of all, what effect will this type of work have on the credibility of the newspaper among its readers? All of these questions need thoughtful consideration and discussion, and no newspaper that wants to do this kind of work should rush them.

In Portland, we have developed guidelines to help editors and reporters through the process of reporting, testing and writing the material. We see six prerequisites:

- the impartiality of the reporter at the start of the project;

- adequate time to master the story;

- thorough research;

- strong editing to test the fact selection and reasoning;

- continual evaluation for a sense of proportion and judgment;

- a note to readers explaining the nature of the project.

We follow each project with extra space for letters and guest columns that are packaged as a response to the stories.

When we undertake a project, we are especially attentive to researching and reporting dimensions of the topic that often get short shrift in typical enterprise stories: the validity of assertions by various sources; the relevance or significance of what they are saying to the issue; the relationship of disparate events or pieces of information; what is not being said but is important, and the resonances of people and events that can not be reduced to empirical data. Clearly, all of this requires degrees of interpretation that are not found in most news features. However, it is the final dimension, the one I call “resonance,” that is the most difficult for reporters to handle successfully and certainly the most difficult for editors to manage. Often it is the flash point in discussion of the new reporting. It generally goes by the name of Maureen Dowd of The New York Times.

Dowd’s ability to see personal idiosyncrasy and turn a phrase is a delight to those who follow her work from Washington. Dowd’s skill derives from her sensibility, her knowledge of her beat, and an acute sense of observation. Of course, the Maureen Dowds come along rarely. Only a few reporters can legitimately enter this territory. Dowd is not the only member of the staff who has more liberty to express her views and her style. The New York Times, with its depth of talent, regularly displays its willingness to give reporters room to connect and characterize events. Its readers get a rich and textured report as a result. Other newspapers show an openness to reporters’ viewpoints as well. The Wall Street Journal encourages reporting that has a perspective on the news. This lead, for example, appeared on a page one story in mid-September 1993 and previewed the content of the Clinton health care program: “President Clinton’s ambitious health care proposal promises to rely on the unseen hand of the marketplace, but its real power stems from the strong arm of the government.” No shyness about interpretation in that news story. The Christian Science Monitor, long a proponent of solution journalism, trusts its reporters to suffuse its news columns with interpretive judgments, and The Miami Herald often ends its investigative series with prescriptions for solving public problems. Perhaps no newspaper is more closely associated with this technique than The Philadelphia Inquirer through the investigative team of Donald Barlett and James Steele. Their work in the series, “America: What Went Wrong,” which strung together the economic events of the 1980’s into a narrative that explained the loss of manufacturing jobs in the United States through mergers, acquisitions and plant closures, is a classic piece of point-of-view reporting supported by extensive research.

An informal survey among my Nieman colleagues also found a willingness among the news organizations represented at Lippmann House this year to draw the viewpoints and judgments of reporters into in-depth news articles. The response from Chris Bowman, a 1995 Nieman fellow who covers the environment for The Sacramento Bee, can stand for many of the thoughtful comments from the Niemans: “The rapidly escalating bombardment of information from television news and magazines shows, from cable, from radio, from the on-line personal computer services, presents a growth opportunity for newspapers. It may not show up on the readership surveys, but I believe the dizzying array of sound bites and megabytes has created a large, unsatisfied need for journalism that makes sense of it all. But it takes courage and an adjustment of newsroom values.” Bowman, like other Niemans who responded to my survey, was cautious about the use of interpretive writing in daily hard news stories. “But there comes a time,” Bowman added, “as with the owls vs. jobs story in the Pacific Northwest, when the story becomes a Ping-Pong match. Newspapers can actually perform a public disservice by limiting the reporting to opinions from opposing camps or offering the only-time-will-tell analyses. The reporter should stop and ask, what about this industry argument that protections for the spotted owl are leading to the demise of the sawmill workers?”

All of this interpretation has not gone unnoticed by press watchers, of course. Doubtful voices are being raised. This is healthy. A press that seeks to interpret needs scrutiny and benefits from it. “The shift to greater subjectivity on the news pages,” the magazine Media Critic complained, “is one of the most significant developments in the news media. It may help explain recent survey data indicating that more and more Americans think media organizations slant the news and cannot be relied upon to provide factual accounts.” Not all reporters accept the new approach, either. In Portland, some reporters are uncomfortable with a forward role on an issue and others lack the confidence to assert judgments. They prefer letting “experts” on the outside draw the conclusions—and the fire.

Clearly, the new reporting touches a nerve of orthodoxy—objectivity. The debate over objectivity is an old one and stretches back, if not to the penny press of the 19th Century, certainly to the philosophical father of the objective-scientific model, Walter Lippmann. But it is important to recall in this regard that Lippmann’s view of the public was that it was incapable of governance and that management of society belonged to an intelligent elite who would be kept in line through fear of the publicity spotlight of the press. “The purpose of news,” Lippmann wrote, “is to signalize an event.”

Dissatisfaction with Lippmann’s vision in one form or another has been a recurrent theme since he articulated it. In an article in the Kettering Review, James Carey, Dean of the College of Communications at the University of Illinois, put the matter succinctly:

“We have inherited and institutionalized Lippmann’s conception of journalism, and the dilemmas of journalism flow, in part, from that conception. We have our new order of samurai but they turn out to be what David Halberstam acidly described as the best and the brightest. We have a scientific journalism devoted to the sanctity of the fact and objectivity but it is one in which the hot light of publicity invades every domain of privacy. We have a journalism that is an early-warning system but it is one that keeps the public in a constant state of agitation or boredom. We have a journalism that reports the continuing stream of expert opinion but because there is no agreement among experts, it is more like observing talk show gossip and petty manipulation than bearing witness to the truth.”

Perhaps the greatest reaction to the press as the signalizer of events came following the excesses of Joseph McCarthy, which were dutifully and uncritically recorded by the press.

It was after the exposure of McCarthy, writes J. Herbert Altschull, that a powerful demand arose for interpretive reporting. “The idea of social responsibility promoted by the Hutchins Commission joined forces with the idealism of the postwar generation of journalists and scholars, led by Curtis MacDougall of Northwestern University, in a campaign to end the practice of blind objectivity and turn instead to more explanatory writing.” In the aftermath of McCarthy, and into the 1960’s and 1970’s, several reactions to news coverage as a flat stenographic report emerged. Altschull has inventoried nine of them: enterprise journalism, interpretive journalism, new journalism, underground journalism, advocacy journalism, investigative journalism, adversary journalism, precision journalism and celebrity journalism.

The type of journalism that I have been describing represents an eclectic mix of existing forms with elements that are new. It often rings with the mission of investigative reporting and develops the depth and detail of enterprise reporting, but it opens new ground by making judgments, as Don Barlett of The Philadelphia Inquirer puts it, based on the “weight of the evidence.” It applies the search for answers, which in investigative reporting tends to focus tightly on law breaking or blatant malfeasance, to broad questions of the performance of public officials, policies and institutions. It also breaks the bonds of enterprise reporting by getting beyond the whipsaw of competing quotes that are so often put in stories to create the perception of balance. The new reporting, which actually counts the early muckrakers as its predecessors, works harder at making a point that the reader can grab than giving all parties to the dispute equal space in the story.

What to call it remains a problem. Our newsroom has not been entirely comfortable with the label “expert journalism” (perhaps for reasons that Professor Carey would have anticipated). One editor suggested we call it “immersion journalism.” Some have included it under the tent of “public journalism.” But whatever its name, it clearly fits with Altschull’s description of the new forms as a reaction against the commonplace press standard of the journalist as mirror.

Behind this more subjective, or activist, approach is the power of information put into a framework of perspective and context. In a sense, it represents a strain of reasoned and informed argument and therein lies its appeal as a kind of provocation to act to solve, or at least debate, problems. Beyond informing readers it can serve a dialectical purpose: It puts forward a set of conclusions that can spark alternatives. Christopher Lasch, the historian and social critic who died earlier this year, made the important point that the public needs argument to develop an appetite for information. Information, Lasch said, is the byproduct rather than the precondition of debate. “If we insist on argument as the essence of education, we will defend democracy not as the most efficient but as the most educational form of government, one that extends the circle of debate as widely as possible and thus forces all citizens to articulate their views, to put their views at risk, and to cultivate the virtues of eloquence, clarity of thought and expression and sound judgment. From this point of view, the press has the potential to serve as the equivalent of the town meeting.”

Its shortcomings notwithstanding, the concept of objectivity keeps a powerful hold on the public imagination and the conventions of news writing. Any idea with as much staying power as objectivity deserves not to be understood too quickly—let alone disposed of. At a minimum, it is an important reminder that reporters should not begin stories with preconceived judgments about the material. Objectivity can be properly reframed as a call to rigor and integrity in the processes of reporting and reasoning. Clearly, in the public mind, factuality is an element of objectivity and ultimately its judgment of the media. The first test of what is read or seen must be whether it is accurate and sound. But what is less clear, because the concept of journalistic objectivity is indistinct and undefined, is the degree to which Americans evaluate the performance of the media based on adherence to certain newsroom protocols of objectivity and the enforcement of emotional and intellectual distance from the subjects that they cover. So while it is no great risk to assert that Americans want newspapers that are fair and impartial in their coverage, the data on media perception may be telling us something other than what the critics of a new subjectivity have inferred.

Take the enigmatic results of the poll by the Times Mirror Center for the People and the Press released in September 1994. It found that 71 percent of Americans felt the news media got in the way of solving society’s problems. Yet a strong majority had a favorable view of daily newspapers (79 percent) and network TV news (68 percent). The poll respondents put daily newspapers third from the top of a long list of political figures, public institutions and social movements, behind only the military and the Supreme Court. To me, this suggests that the public maintains a reservoir of goodwill for the concept of a free press in the life of the nation but simultaneously harbors deep disappointment about the way the press applies itself and its influence to move the society forward to solve its problems.

This, to me, is the point that is missed so frequently by those who look to marketing solutions to revive newspaper readership. The marketing people intuitively, and correctly, sense some disconnection between readers and newspapers, some lack of synchronization on what readers want and what appears in the newspaper. So they design surveys that bring answers to their questions, not the questions of readers. The results are better television books, more color, and zippier entertainment sections. These are all good things for newspapers, and they can be circulation builders, but lost in the process is the recognition of the power of lining up resources and energy behind what the public sees as the core and defining purpose of newspapers, which is to inform the public so that it can function in a democratic society. The best marketing plan is quality content in a newspaper that engages the mind and imagination of its community.

All of which is to suggest that flat or declining newspaper circulation around the nation may be a sign of the public’s rejection of a press ethos that puts institutional caution or parsimony ahead of the courage and skill it takes to find new ways to bring clarity, force and reader appeal to the tough stories, the ones that need to get written.

If indeed readers would prefer a press that is more actively engaged in problem solving, or in explaining events and issues in terms that allow readers as citizens to understand and solve problems, then newspapers need to craft news reports that convey meaning as well as fact, insight as well as events. And the one figure who is key to this kind of journalism is the well informed reporter. A newspaper’s decision to adopt a more interpretive approach to the news must be followed by a commitment to developing the research and analytical skills of reporters.

The debate needs to shift away from whether Americans need more or less objectivity in their newspapers to a better understanding of what it means to provide readers with accuracy, relevance and utility. Let’s posit fairness and impartiality as the platform on which all parties to the debate can stand and move ahead to figure out how the press can better create understanding about why many schools fail to educate children, what is wrong and what is right with the nation’s health care system and what that suggests about reform, and how to account for the bulging population of our prisons.

As Seymour Topping, former Director of Editorial Development for The New York Times Co. Regional Newspapers, wrote while he was President of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, “There is agreement in our profession that the press has furnished enough facts. The question at issue is whether the press has provided the understanding of what those facts mean to enable the citizenry to cope with the problems confronting them.”

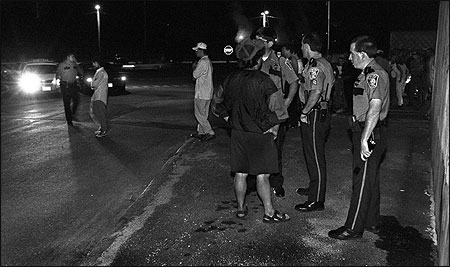

Tensions are high following a fight at closing time outside a Rumford (Maine) bar. Photo courtesy of the Maine Sunday Telegram and Portland Press Herald.

A Portland police sergeant performs an initial field sobriety test on a Portland woman after she was involved in a single-car accident. She was charged with operating under the influence. Photo courtesy of the Maine Sunday Telegram and Portland Press Herald.

Lou Ureneck, on leave from his position as Editor and Vice President of the Portland (Maine) Newspapers, is the 1995 editor in residence at the Nieman Foundation. Ureneck also is the incoming Chair of the New Media and Values Committee of the American Society of Newspaper Editors.