I grew up in New York City—the Bronx—a few blocks from Yankee Stadium. I’ve lived and worked in cities all my life. The sense of place one gets from cities is naturally different from that of small towns like the ones I’ve depicted in my books. That, I’m sure, helped my writing and photography. Everything in Down East Maine was different and, therefore, fascinating to me as a documentarian. People just didn’t do stuff like dig clams or tag bears within sight of the Grand Concourse.

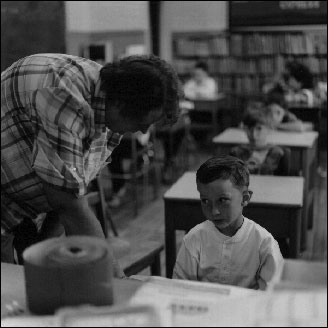

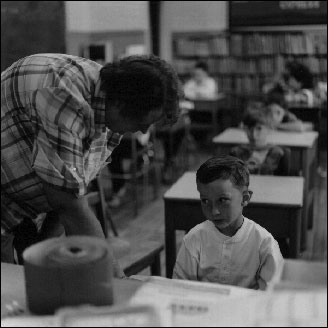

Then, too, there are the people themselves. What passes in the common folklore for the true Mainer is a taciturn, humorless Joe, who doesn’t care a whit for anyone “from away.”

For everyone like that, I’ve encountered dozens more who display a trenchant wit, true warmth and an admirable talent for surviving in a land that is as harsh as it is beautiful. The storied Maine aloofness is better described as a shy reserve, tempered by that rarest of commodities, good manners.

To the Bronx boy who spent his travel time on the subway and whose encounters with trees were infrequent and strange, Down East Maine was a place of raw and fragile beauty. It was a place where you could walk in the woods for hours without encountering a soul; where the music of the evening was in the birds and the crickets, and where the starlit night sky—undimmed by competition from civilization below—burned with a rare spectacular brilliance.

Is it any wonder I was smitten?

The danger, of course, is to romanticize, to gloss over the poverty or the difficulty of making it in a remote, unforgiving environment. So I am proud of what one Maine reviewer said of my effort in her tiny weekly:

“One of those very special books that pays tribute without gushing, is truthful but never grim, and manages to beguile without fantasizing….”

No journalist could seek higher praise.

Working the Tide

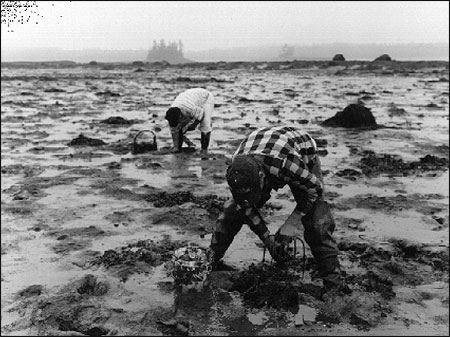

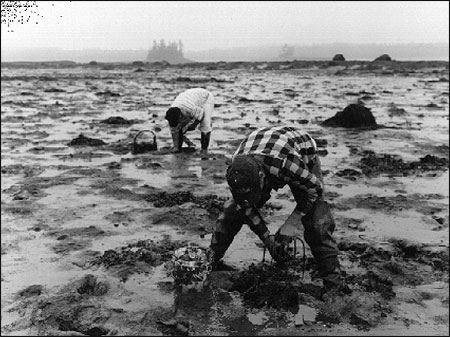

Text and photographs by Frank Van Riper.Only blueberry raking matches it for backbreaking toil.

Clamming—digging for soft-shelled clams in unyielding wet clay with a short, heavy clam rake—is one of the toughest ways to harvest seafood because it is done by hand, a few clams at a time. And it can’t be done in water.

Clammers watch the tide tables as assiduously as lobstermen. Only, unlike the fishermen, the clammers wait for dead low tide, when coves are turned into mudflats thanks to the amazing pull of the Bay of Fundy. (They also watch for, and respect, warnings of red tide; the plankton-produced toxin can temporarily make clams and quahogs that have fed on it poisonous, if not deadly.)

When the water drops, be it in a cool fog or under a hot sun, the high rubber boots go on as the clammers wade ponderously into the flats, searching for the telltale blowholes in the mud, indicating that clams are lurking beneath the surface. A good day of digging can yield several baskets of clams, which then are sold, mostly to local restaurants or stores.

Every summer, one can count on seeing a tourist who is taken with the idea of clamming for his or her evening meal. One also can count on that tourist quickly tiring of the game and heading for the local takeout stand for a mess of juicy, sweet fried clams that, likely as not, were harvested hours before—by somebody else.

Frank Van Riper is a 1979 Nieman Fellow. His book, “Down East Maine: A World Apart,” was published by Down East Books, Camden, Maine, $29.95.

Then, too, there are the people themselves. What passes in the common folklore for the true Mainer is a taciturn, humorless Joe, who doesn’t care a whit for anyone “from away.”

For everyone like that, I’ve encountered dozens more who display a trenchant wit, true warmth and an admirable talent for surviving in a land that is as harsh as it is beautiful. The storied Maine aloofness is better described as a shy reserve, tempered by that rarest of commodities, good manners.

To the Bronx boy who spent his travel time on the subway and whose encounters with trees were infrequent and strange, Down East Maine was a place of raw and fragile beauty. It was a place where you could walk in the woods for hours without encountering a soul; where the music of the evening was in the birds and the crickets, and where the starlit night sky—undimmed by competition from civilization below—burned with a rare spectacular brilliance.

Is it any wonder I was smitten?

The danger, of course, is to romanticize, to gloss over the poverty or the difficulty of making it in a remote, unforgiving environment. So I am proud of what one Maine reviewer said of my effort in her tiny weekly:

“One of those very special books that pays tribute without gushing, is truthful but never grim, and manages to beguile without fantasizing….”

No journalist could seek higher praise.

Working the Tide

Text and photographs by Frank Van Riper.Only blueberry raking matches it for backbreaking toil.

Clamming—digging for soft-shelled clams in unyielding wet clay with a short, heavy clam rake—is one of the toughest ways to harvest seafood because it is done by hand, a few clams at a time. And it can’t be done in water.

Clammers watch the tide tables as assiduously as lobstermen. Only, unlike the fishermen, the clammers wait for dead low tide, when coves are turned into mudflats thanks to the amazing pull of the Bay of Fundy. (They also watch for, and respect, warnings of red tide; the plankton-produced toxin can temporarily make clams and quahogs that have fed on it poisonous, if not deadly.)

When the water drops, be it in a cool fog or under a hot sun, the high rubber boots go on as the clammers wade ponderously into the flats, searching for the telltale blowholes in the mud, indicating that clams are lurking beneath the surface. A good day of digging can yield several baskets of clams, which then are sold, mostly to local restaurants or stores.

Every summer, one can count on seeing a tourist who is taken with the idea of clamming for his or her evening meal. One also can count on that tourist quickly tiring of the game and heading for the local takeout stand for a mess of juicy, sweet fried clams that, likely as not, were harvested hours before—by somebody else.

Frank Van Riper is a 1979 Nieman Fellow. His book, “Down East Maine: A World Apart,” was published by Down East Books, Camden, Maine, $29.95.