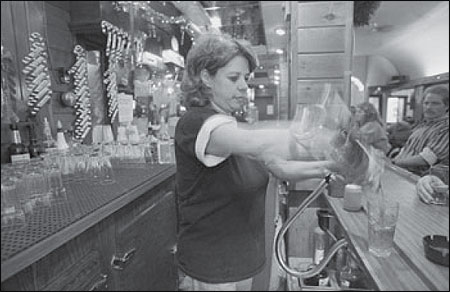

Tara Fatz, manager and former owner of the Lobby Bar in downtown Great Falls, Montana, says people are lined up at the door when she opens for business at 8 a.m. Photo by Larry Beckner/Great Falls Tribune.

My job is to amplify the voices of those who often go unheard. It is vital that everyone understands how our laws and policies actually affect people’s lives, so a large part of my work as a journalist has been to help people voice concerns and express fears about circumstances they confront. Recently my reporting took me from Skid Row to the state prison to mental health hospitals as I explored alcoholism. Along the way, I came to understand more fully how alcohol connects these three public places and institutions and how future brain research might lead to solutions for some of the behaviors we now label as normally abnormal—unacceptable conditions that we have come to accept.

This odyssey began four years ago when I proposed doing a conventional, weeklong series of stories on alcoholism for the Great Falls (Mont.) Tribune. Other editors thought my original proposal didn’t address some aspects of the situation, so Executive Editor Jim Strauss suggested expanding the series to 12 parts and publishing one part each month for the calendar year 1999.

We did just that. We called the series “Alcohol: Cradle to Grave,” a title as broad as Montana’s skies. It ultimately blossomed into about 50,000 words of copy—a huge commitment for a newspaper with just a score of reporters and a circulation of about 40,000 on good days. Ultimately, the series won the Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting in 2000.

Unearthing the Facts About Alcoholism

Not surprisingly, I learned a lot during a brutal year of meeting monthly deadlines. I wrote on subjects as diverse as fetal alcohol syndrome and addiction within our prison system. I shared with readers what I learned about the psychological harm of growing up in an alcoholic household and the physical damage alcohol does to human bodies. Among the other lessons my reporting unearthed are these:

Alcoholism is a medical disease. Although social stresses play an important role in a person becoming an alcoholic, alcoholism tends to run in families in which a chemical imbalance in the brain’s neurotransmitters is a hereditary trait. Sons of alcoholics are four times more likely to become alcoholics themselves, even if they are raised in foster homes by nonalcoholic parents. Researchers have also bred lab rats indifferent to alcohol, as well as others that actively seek it out or are repulsed by it.

I talked with many alcoholics who vividly remember the first drink they ever took. They speak of it making them feel as though they fit in for the first time: Suddenly, they were brilliant, exuberant, alive. Researchers now believe that feeling occurs because alcohol hijacks the dopamine system, which is the body’s natural reward center. Dopamine normally gives a feeling of intense well-being to activities that are good for the body—things like eating well or sex or exercise (a runner’s high is produced by dopamine). For some people, getting drunk gives them this extra sense of euphoria.

Alcohol is everywhere. The first installment of the series looked at a day in the life of Great Falls. At dawn I was in the Rescue Mission, then moved to a DARE classroom by 8:30, the morning “suds and soaps” hour at a bar at 9:30, an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting at 10:00, a recovery center at 10:30, municipal court at 11, a bartender training class at 11:15, and so on. During that evening, I rode with a police officer who handled eight calls: All but one involved alcohol. I came to see alcohol as an invisible river that runs through our lives uprooting people and flooding out families, much like the Missouri River that runs past our newspaper offices. Occasional floodwaters are seen as an act of nature just as excessive drinking is seen as human nature. Their ravages come as no surprise.

Alcoholism is a costly disease. One Great Falls family and marriage counselor, Wava Goetz, reviewed the 700 cases she had handled over the past five years and came to a stunning discovery. She found that alcohol was a factor in two-thirds of them. “Without alcohol, I’d probably be out of business,” she told me. “And that would be a happy day.” State welfare workers in Great Falls estimate that half their clients’ lives were so impaired by alcohol that they couldn’t work. The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that alcoholism costs American businesses more than $100 billion a year. “Thirty to 50 percent of all hospital admissions nationally are related to alcohol,” said Dr. Dan Nauts, medical director of the Benefis Healthcare Addiction Treatment Center.

I visited the Montana State Prison at Deer Lodge, where I found 85 percent of the inmates are locked up for crimes fueled by alcohol or drugs. In 1998, the state spent $46.8 million locking away its adult criminals and another $1.5 million on pre-release centers and parole officers. Those figures don’t include expenses for county or city jails. “I know a few people in here who say they don’t have a drug or alcohol problem,” said inmate Marty Quick, “but I don’t believe I know any that I actually believe.” As Joseph A. Califano, Jr., chairman of The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University put it, “Contrary to conventional wisdom and popular myth, alcohol is more tightly linked with violent crime than crack, cocaine, heroin or any illegal drug.”

In examining the costs of alcoholism, I realized that like the river of alcoholism running through our lives, some of this disease’s costs are known while others remain invisible. With the help of the governor’s budget director, Dave Lewis, I asked state agencies to tell me how much of their spending could be directly attributed to alcohol. I also asked them to estimate the hidden costs, including such things as the state’s prison population and welfare caseload.

When the numbers were compiled, we concluded that the hidden costs of alcohol abuse might total at least $135 million in Montana. “I can’t quarrel with your numbers,” Lewis later told me. “It’s certainly eye-opening to see the amount of money that alcohol costs the state.” This amount is more than the state spends on its university system, about $120 million each year.

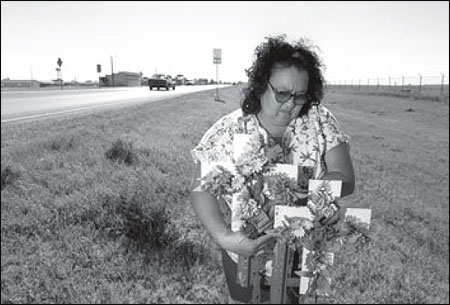

Paula Firemoon keeps these crosses on Highway 2 in Poplar, Montana decorated in memory of her two daughters, Lorriane and Jessica Brien, who died in a car accident when they were hit by a drunken driver in 1992. Photo by Larry Beckner/Great Falls Tribune.

Lessons a Journalist Learned

As I reported this story, there were also valuable lessons I learned as a journalist.

Believability comes through personal connection. To make these stories believable to our readers, I knew we had to use names and photos of the people I interviewed. That proved extraordinarily difficult. Imagine being asked to reveal your darkest secrets, then having them—along with your name and your picture—printed on the front page of your local newspaper. But because in the second part of our series we so prominently and forcefully labeled alcoholism as a disease, the stigma was reduced. In addition, most recovering alcoholics are compelled to take responsibility for their lives and to help others, both of which could be achieved by going public with their stories.

Sources should be treated with consideration for their circumstances. I felt that people whose careers and personal lives could be jeopardized by what I wrote should have the opportunity to read their stories before publication. We used this procedure sparingly, but found it was an excellent quality-control mechanism. A 22-year-old victim of fetal alcohol syndrome, Lissy Clark, whose brain was damaged before she was born by her mother’s drinking, was the first person to whom I offered this opportunity. Lissy had told me a story of how she answered the front door at home one day and found a young man who invited himself in, walked to her bedroom, removed their clothes and had sex with her. She didn’t understand that such behavior was wrong. I didn’t want to victimize her again (and we have a policy about not naming rape victims), but her story was also a compelling illustration of the problems she faced. I used the rape as the lead of my story, then took the story to her and asked her to share it with her stepmom, her counselor, her priest, or whomever she chose. Three days later, I returned (with my heart in my mouth) to find that Lissy and her stepmom agreed that this experience so perfectly illustrated the problem that it had to be printed. They did, however, have a few other minor corrections that only improved the story.

The rights of people should be protected. Our stories had to demonstrate our respect for the rights of other people, particularly those who have been victims. I had been invited to visit a meeting of Al-Anon, a group similar to Alcoholics Anonymous that helps the families of alcoholics. Although I had introduced myself as a reporter and openly taken notes during the meeting, a delegation of women met me at the door and requested that I leave my notebook behind. They explained their tradition that what was said in the room remained in the room. Journalistically, I had no reason to comply since they knew who I was and spoke anyway. Again, however, I didn’t want to revictimize them. Ultimately, these women agreed to sit with me in a local park and tell some of the same stories in ways that didn’t hurt family members who read my article. Understanding their rationale, I agreed.

I didn’t understand the full consequence of that decision until about a month later when I was interviewing members of a different family. Mary Keeler asked me how I’d handled the situation at Al-Anon, and I told her about the second interviews. “I know,” she grinned. “That’s the only reason we’re here tonight. If you had tried to screw those people over, no one in town would have talked to you again.”

Eric Newhouse is projects editor of the Great Falls Tribune in Great Falls, Montana. His yearlong series of stories on alcoholism won the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting in 2000. It has been rewritten as a book, “Alcohol: Cradle to Grave,” which was published in September 2001 by Hazelden Information Education.