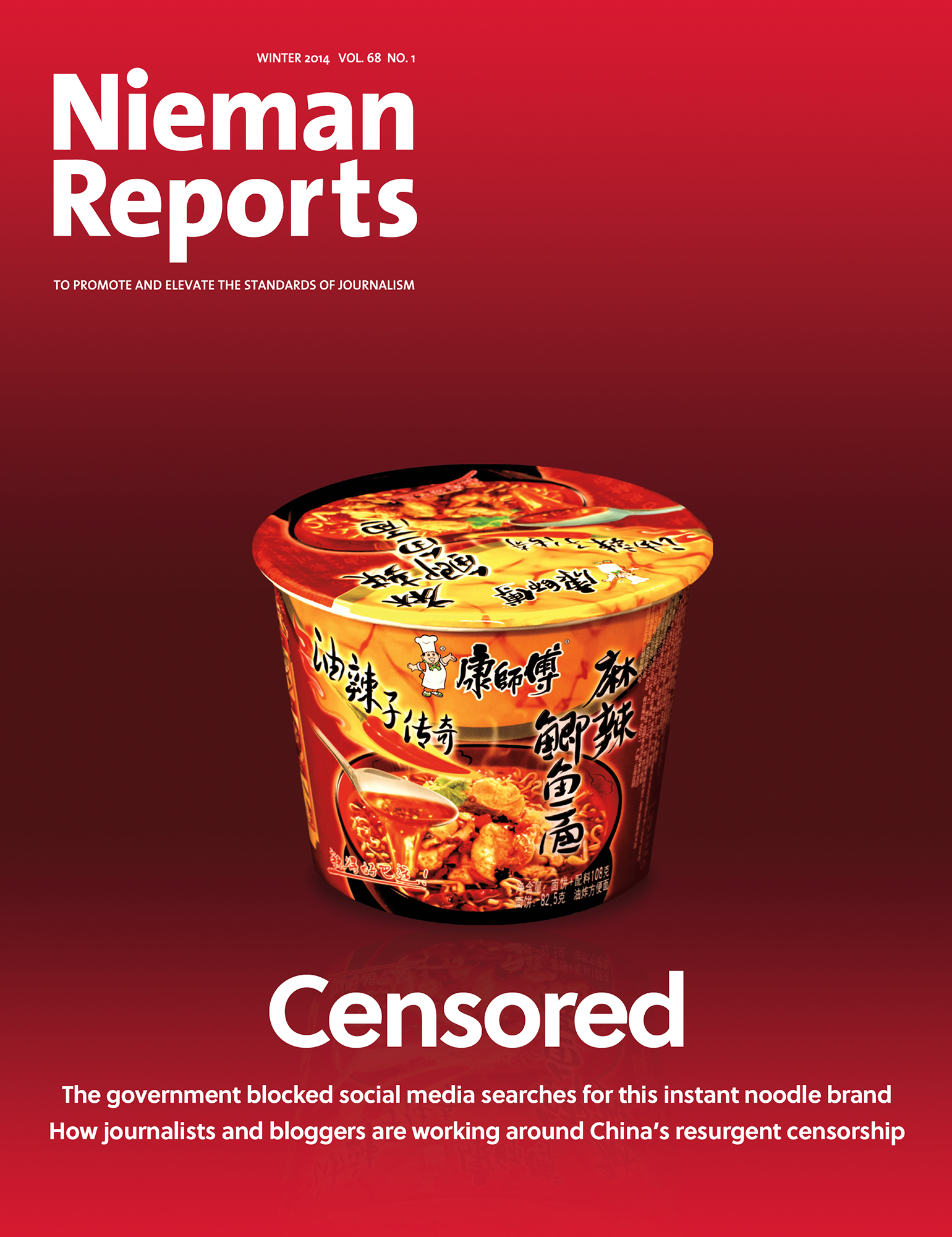

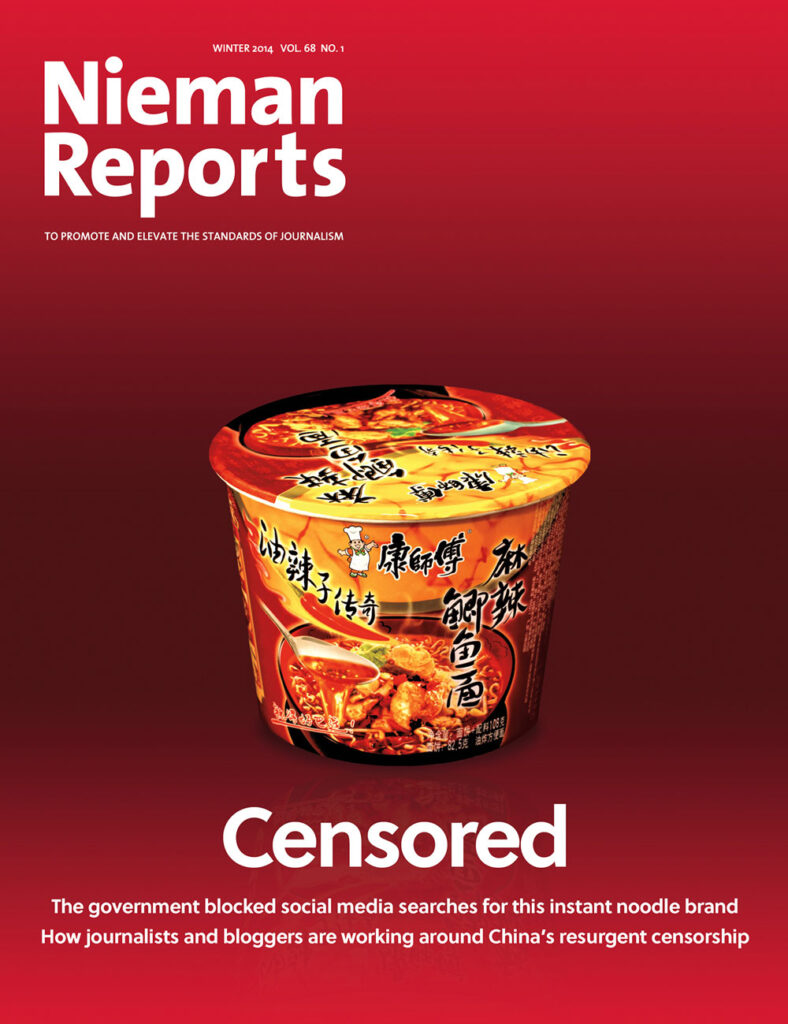

For the cover of the new issue of Nieman Reports, we wanted to say something intriguing about the state of journalism in China. Many of the stories in the cover package tackle the issue of what cannot be published in China so Nieman Reports design director Stacy Sweat mocked up a couple covers with taboo images.

For the cover of the new issue of Nieman Reports, we wanted to say something intriguing about the state of journalism in China. Many of the stories in the cover package tackle the issue of what cannot be published in China so Nieman Reports design director Stacy Sweat mocked up a couple covers with taboo images. In a visual nod to censorship, a Czech visual artist removed the tanks from the iconic photograph of Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989. Yet, when we showed the cover around the office, it was clear that the manipulated image did not have an immediate connection to the original. The better option was to run them side by side on the opening spread of the cover story.

In a visual nod to censorship, a Czech visual artist removed the tanks from the iconic photograph of Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989. Yet, when we showed the cover around the office, it was clear that the manipulated image did not have an immediate connection to the original. The better option was to run them side by side on the opening spread of the cover story.We entertained more ideas but the one that stuck was a cup of instant noodle soup. The name of this popular Chinese brand bore a close resemblance to the name of a disgraced Chinese leader. To get around a ban on mentioning the leader’s name on social media, netizens substituted the noodle brand. We then faced the challenge of finding a cover-worthy image of the packaging. After deploying colleagues in China and Taiwan, we ended up finding the product a bit closer to home—at an Asian grocery store in Boston.