We were on a Zoom family call for my uncle's birthday attended by dozens of relatives around the world – India, Pakistan, Hong Kong, Australia, USA.

“Did you see the latest Nieman Reports?” asked Zawwar Hasan, Nieman ’67.

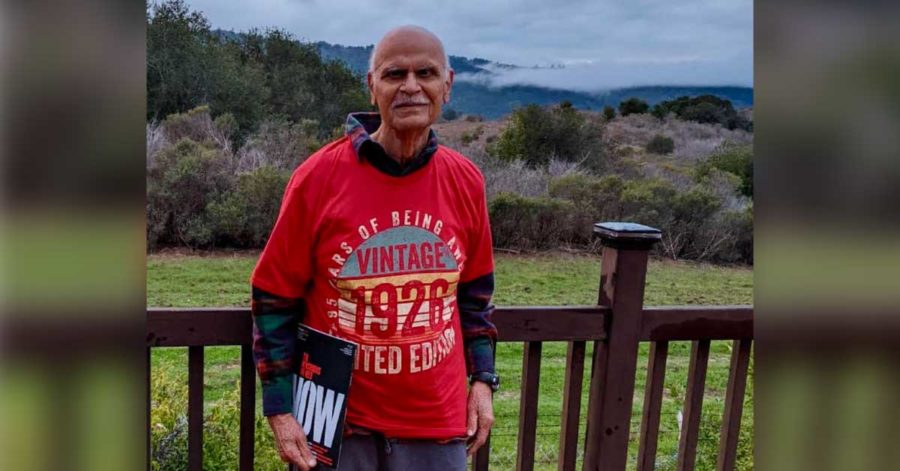

Zawwar is my mother’s eldest brother, whom I call Mamoo. He turned 95 on January 27, 2021. He is clearly more up to date with the Nieman Reports than me, his niece and a 2006 Nieman fellow.

“You must read it. It’s one of their best!” he said, referring to the Fall 2020 issue -- “The Newsrooms We Need Now.”

In 1949, he walked into the office of the Associated Press of Pakistan (APP) in Karachi, then capital of the new nation-state, looking for a job. The only reporting experience Mamoo had was filing sports stories for a local journalist back in his hometown Allahabad, now across the border in another country, India.

The editor, took him on for a three-month trial and sent Zawwar out to report on a cricket match. Akhtar, my father Sarwar’s older brother, was reporting on the match for Pakistan’s leading English language newspaper, Dawn. He was also from the Allahabad area, and the two instantly struck up a friendship.

I owe my existence to that encounter and friendship, that led to my parents meeting in 1961.

Akhtar died after catching pneumonia in 1958. The only known cure was penicillin, not widely available then. As a medical student, Sarwar met penicillin’s discoverer, Sir Alexander Fleming, at Dow Medical College, Karachi, 1951; they were photographed together in a small group portrait of faculty and student representatives. Since then, the drug has saved countless lives. Millions around the world may relate to this with the coronavirus pandemic and vaccines now being rolled out.

My mother, Zakia, a college teacher, met Sarwar after Mamoo and his family moved back to Karachi in 1961. They had been living in Lahore since 1954 when they came from India to join Mamoo, then APP’s Chief Correspondent in the city. Their family doctor in Karachi was Sarwar. Zakia would take Mamoo’s children to his clinic not far from where they lived.

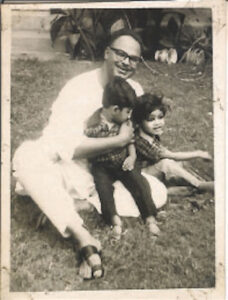

When Mamoo went with his family, including three children, for the Nieman fellowship in 1966 - there was no concept of “Nieman kids” [children accompanying parents during the fellowship experience] but international fellows had host families, a concept that deserves revival.

On his last visit to Boston, in 2007, Mamoo had a moving reunion with his host family, the Kornfelds, a local couple whose children were roughly the same age as his own. George passed away a few years ago, but Hulen Kornfeld, who still lives in the Boston area, joined Mamoo’s 95th birthday celebrations.

In Mamoo’s time, the Nieman fellows were all men.

His classmates included Ken Clawson, later director of White House communications in the administration of President Richard M. Nixon and one of his staunch defenders during the Watergate era.

Visiting New York in 1972 for a meeting, Mamoo called Clawson. The conversation went something like this:

Clawson: “How long are you here?”

Mamoo: “Tomorrow night”

Clawson: “No you’re not! You’re coming to DC.”

So Mamoo went to the White House. Nixon was in China at the time, a groundbreaking trip that ended 25 years of isolation between the two countries.

Mamoo remembers Clawson’s office, the Press Room, a swimming pool … Clawson introduced him to Gen. Alexander Haig, Nixon’s controversial chief of staff, emerging from a press conference.

As a Nieman Fellow, Mamoo took courses in international affairs, developmental economics, and comparative religions. He played squash and dined at the Faculty Club with classmates and Harvard professors.

Henry Kissinger then taught at the Department of Government and headed the Harvard International Seminar.

“Kissinger would sit with us and ask us if we thought he was doing things correctly,” recalls Mamoo.

Mamoo’s earlier visit to the U.S. was through a program with a State Department journalism program and the University of Missouri School of Journalism’s Project for Foreign Newspapermen in 1957; involving reporters from Taiwan, Iran, Pakistan, and South Korea. A newsletter shows Mamoo at The Denver Post, in Denver, Colorado; The Lawrence Daily Journal-World, in Lawrence, Kansas; and The Mexico Ledger, in Mexico, Missouri.

Mamoo reported on three Olympics: Melbourne, 1956, and Rome, 1960, for APP, and Sydney 2000 - almost 30 years after leaving the field - on special assignment for Dawn, the paper he joined in 1960 as chief reporter, “ten years late,” as Dawn editor Altaf Hussain told him; he had asked the APP head several times to release Mamoo.

After his Nieman year, Mamoo joined The Morning News in Karachi as a senior editorial writer. During a newspaper strike in Pakistan in the late 1960s under the then military rule of Gen. Yahya Khan, he joined his striking colleagues on a footpath in front of the newspaper office.

Emotions ran high as the protesters urged all newspapers to join them. Mamoo opposed the idea, reasoning that there was no point pressuring papers that were already toeing the line. Many journalists couldn’t financially afford to go on strike. The lawyer advising the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists, Abdul Hafeez Peerzada, agreed. The journalists’ union did not.

Mamoo still sat with the strikers in solidarity. The military authorities pressured the editor into sidelining him from editorials to the obituaries section. He resigned.

A newly launched daily, The Sun, snatched him up. After some time there, Mamoo left to launch a groundbreaking travel magazine, Focus on Pakistan, for the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation. In 1973, he joined Pakistan International Airlines’ public relations department. He retired ten years later as General Manager Advertising.

Although Mamoo left the profession in the mid-1970s, long before I joined it, he has remained a journalist at heart and always encouraged me. In fact, he is far ahead of his time in his support for female colleagues. While still in college he coached and guided his sisters; both went on to become trailblazers in their fields.

In the mid-1990s, when moving to the U.S. he passed down to me a prized possession from his Nieman year, a wall poster about the ethics of journalism.

When I didn’t get the Nieman fellowship the first time I applied, he urged me to try again. Ten years later, I applied for various fellowships. “Even if you get one of them, wait till you hear back from Nieman,” he counselled. “It’s the best.”

The video compilation of greetings for Mamoo’s 95th birthday includes a message from Ann Marie Lipinski, the Nieman Foundation’s first woman curator. Mamoo was thrilled when she was appointed.

“Look after yourselves, stay strong, stay healthy, stay happy,” said Mamoo, in his video message of thanks.

A plea all the more relevant in a pandemic-inflicted world.

Editor's Note: Due to reporting errors, the article has been updated to reflect the correct years of several of Zawwar Hasan’s encounters and reporting assignments.