Amid a pandemic that has killed over 5 million people globally, the need for clear, accurate information has never been more apparent. And yet many communities lack the crucial information they need to make important decisions for themselves, their families, and their communities.

How often have you seen a street closure or police emergency in your neighborhood and were unable to find out what was happening online? Even in well-served communities, basic essential information — such as “Where can I get a Covid-19 test?” or “Where should I go to vote if my polling place is closed?” — can be missing or hard to find. While many people feel overwhelmed, stressed, or fatigued by the volume of news and content available, much of what is flooding their inboxes, screens, and social media channels is incorrect or repetitive. And a lot of useful and relevant information people want and need is simply absent. It’s possible for our news diets to be both obese and malnourished.

That’s why I’m launching a new journalism and information equity practice at DoGoodery, a sustainability consulting agency that creates and executes initiatives to improve lives and reduce inequity. The new practice will work with organizations across the news and information ecosystem — including newsrooms of all shapes and sizes, tech providers, corporations, academic institutions, nonprofits, and philanthropic organizations — to help grow real, inclusive journalism and information equity, especially in under-covered communities.

We’re offering a diverse team of digital news experts — including experts on audience development, market research, revenue, events, multimedia formats, and diversity, inclusion, and equity work — to assess news organizations’ needs, taking the time to deeply understand their audiences, opportunities, challenges, and team dynamics. We will create a realistic, custom plan to meet their goals, and execute it. The idea is to bring newsrooms closer to their communities and help them better serve marginalized or underrepresented groups as we identify and launch business models that tie their social impact and how well they serve their audiences to their financial sustainability.

By doing the hands-on work of inviting audiences in, listening to their needs and stories, and making news more inclusive, equitable, and accountable to more communities, we hope to cut through the noise and make journalism more relevant to people’s lives. Our goal is to help fact-based journalism thrive, one organization at a time, and to bring more information that matters to people who don’t have access to it today.

Related Reading

Nikole Hannah-Jones and the Need for BIPOC-Serving News Organizations

By Amoretta Morris and Sara Lomax-Reese

How Journalism Moves Forward in an Age of Disinformation and Distrust

By Danielle Belton

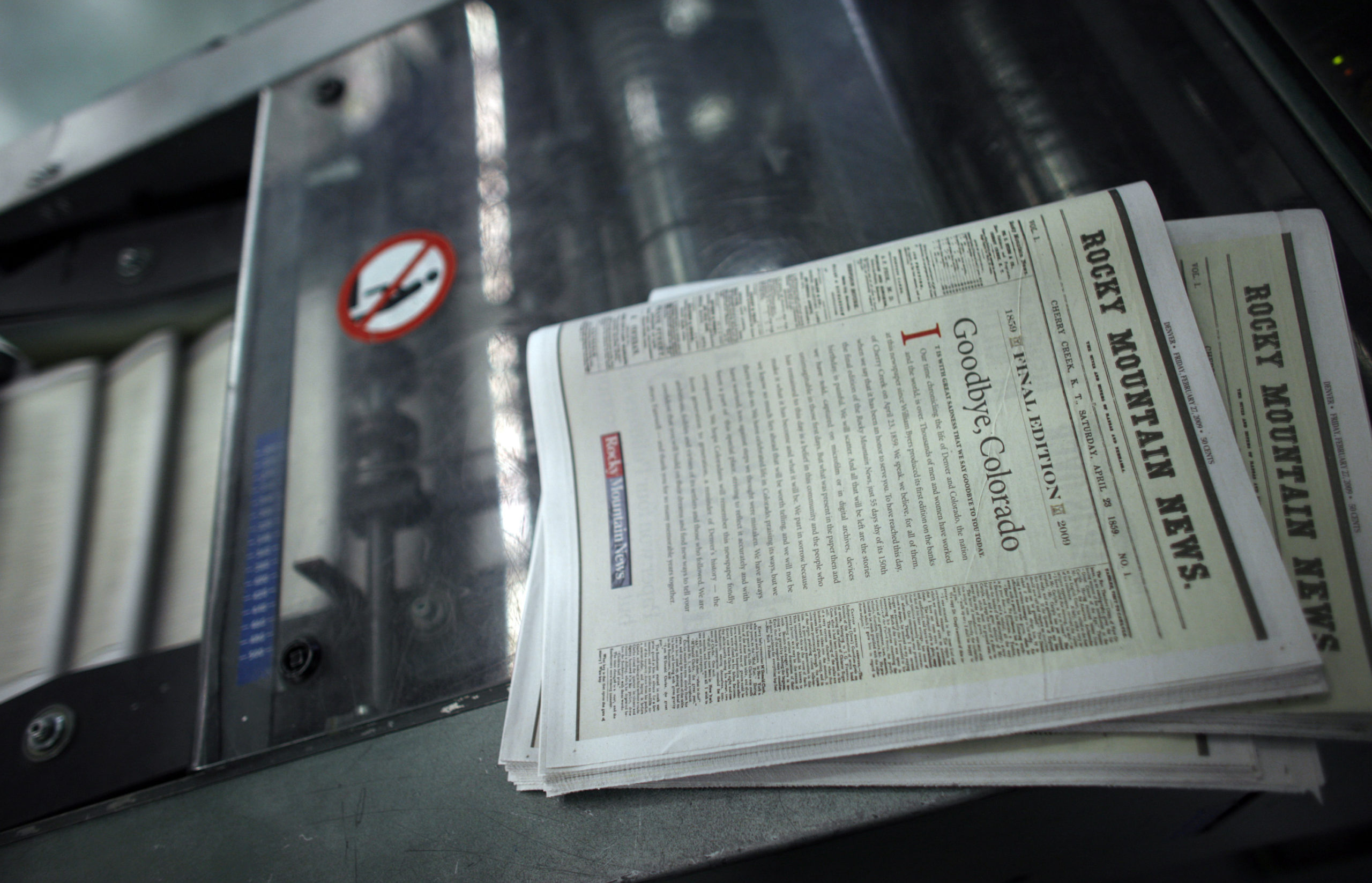

Here’s why this venture is so important: According to University of North Carolina research published last December, “200 counties do not have a local newspaper, nearly 50% of counties only have one newspaper, usually a weekly, and more than 6% of counties have no dedicated news coverage at all.” A quarter of all U.S. newspapers have closed in the last 15-plus years, according to another UNC study. And many of those that remain have had to cut back: The Pew Research Center reported this year a 26% decline in newsroom employment since 2008, with a third of large newsrooms going through layoffs last year.

Bad or missing information has exacerbated many urgent issues, including white supremacy, hate crimes and racial equity; voting rights; health, the pandemic and vaccine hesitancy; education; climate change and much more. The dynamic is exacerbated in crises, including natural disasters and other emergencies, when people need good, clear information most urgently.

If we want to solve any of the big societal problems we’re facing, we must tackle the information crisis — what some people are calling an “information pandemic” — head-on and find ways to support news gathering that reflects and serves all our communities. Access to true information is essential, not only to our democracy, but also to social equity and individuals’ abilities to make informed decisions about their own lives.

And that won’t happen unless we find ways to make news for and about more people and make the truth as attractive as the lies. Much of our work at DoGoodery will center on understanding the impact — and sometimes harm — journalism has had on various communities. By taking responsibility and refocusing our efforts to bring new voices into the conversation, I believe we can help reverse the information crisis.

The importance of a free press and access to information have long been recognized by the international community: They are considered both civil rights and human rights, included in more than 50 constitutions and also the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights signed in 1948. As the UN Convention Against Corruption notes, 129 countries have access-to-information laws.

When governments restrict freedom of the press or access to information, it’s easy to see those actions as violations of these rights. When the erosion of these rights is due not only to government action (or inaction) but also to market forces, the question of where to place the blame gets more complicated. Journalism has suffered from tech and business model disruption, algorithms, competition for attention from a flood of other content, and issues within the news industry itself, such as a serious lack of inclusion and representation. But those reasons don’t make the information gaps and news deserts any less of a problem for the people affected by them.

It will take a lot of work to solve this, and there are glimmers of hope: the growth of nonprofit media and philanthropic support of local news, the launch of new BIPOC-led news organizations, a focus on building two-way audience engagement and community, and innovative new models to support local news and fill news deserts. That said, more action is needed to confront the scale of the problem, with a whopping 2,100 U.S. publications closing since 2004. This information crisis is not something that can be fixed by regulation, technology, philanthropy, corporations or even by the journalism industry alone. My team believes we can connect those dots for newsrooms and organizations looking to create information equity.

Like climate change, poverty and hunger, health disparities, education, and racial and gender equity gaps, the information crisis should be considered an urgent sustainability issue that will take many solutions and many people working together to turn around. And I think it should be a focus for anyone who cares about having a positive impact on the world, whether individuals, companies, government agencies, nonprofits, or foundations.

With DoGoodery’s expertise on sustainability projects, and my experience across editorial, audience, revenue and innovation in journalism, we’re committing to help solve the information crisis by growing information equity and helping news organizations thrive. I hope you will join me.