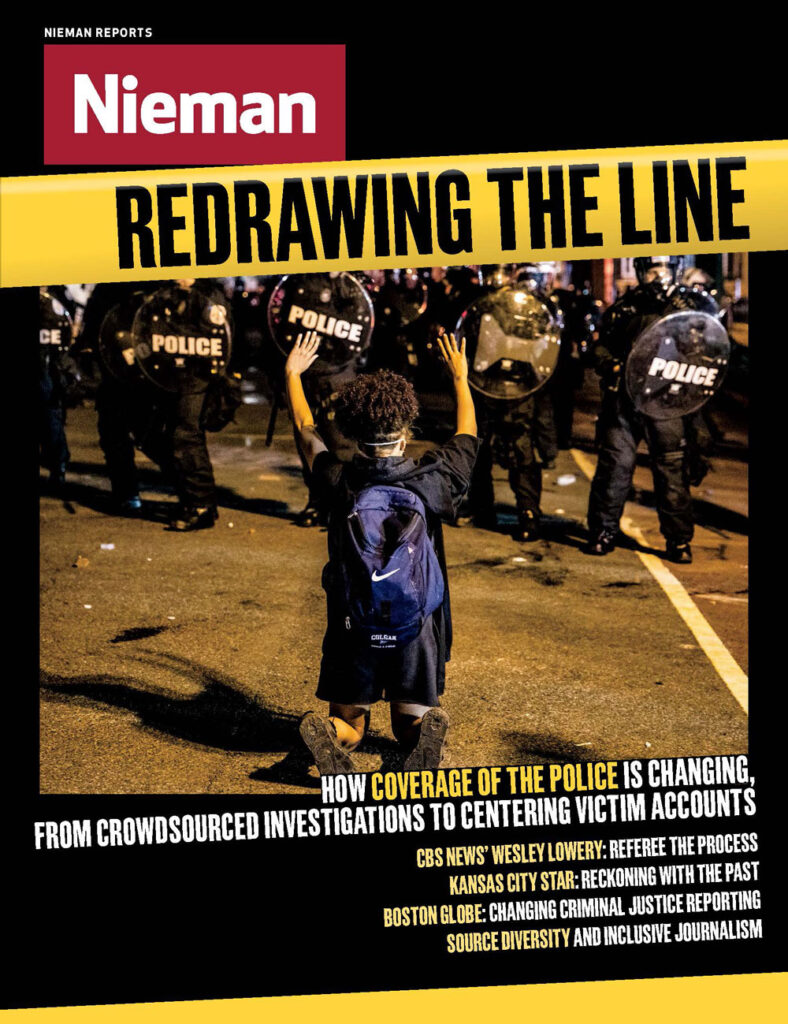

What I saw the next afternoon near Kansas City’s Country Club Plaza shopping district were hundreds of sign-toting protesters of various ages and ethnicities. They chanted and screamed their opposition to police brutality against Black men and women. They directed their anger at officers in riot gear lined up two- and three-deep around the protest area.

One step or slip from the sidewalk into the street and police threw protesters to the ground, handcuffed them, and herded them into the back of a cruiser. Police repeatedly doused the chanting, but not violent, crowd with chemical repellents.

Such protests played out around the country last spring after the police killings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and other unarmed Black people. Even after nearly 40 years as a journalist, I found the Plaza scene chilling, but not at all what I’d heard reported the night before. From my vantage point, police — not protesters — were the agitators.

Later, after scrubbing the chemical repellant from my face and hands, I became emotional. It was one of those moments when the story grabs hold of your gut, ties it in knots and tugs. Sickening.

The events of the spring were painful for a lot of people, including Black reporters covering this movement and the resistance to it. It’s been challenging because it’s not possible to shed your Blackness. It’s more than skin deep. I deeply felt that protest, from the perspective of the protesters.

When the anger — that in 2020 we were still fighting racism, systemic and overt — subsided to a slow burn, it became clear that what I had actually witnessed that afternoon was Kansas City joining a national movement, ready to tussle with racial injustice in all its forms. This Black reporter wanted a piece of that; writing about one spring afternoon protest was not enough.

I was fairly certain that newspapers across the country had played a role for decades in perpetuating racism through their coverage — and lack of coverage — of Black people, Black culture, Black lives. With the country in the midst of a reckoning on race, I thought, what better time than now for The Star, one of the most prestigious news organizations in the Midwest, to take an accounting of its role in spreading the racist attitudes woven into the fabric of this country to oppress an entire people.

I wasn’t the only one tugging at that thread. A metro editor at The Star had a similar thought: The paper needed to make a statement about its racist past.

I proposed, first in an email to top editors and then in a conference call, that The Star make a public apology for our failure to adequately and accurately tell the rich stories of Black people’s contributions in Kansas City. Apologize for rendering Black Kansas City all but invisible.

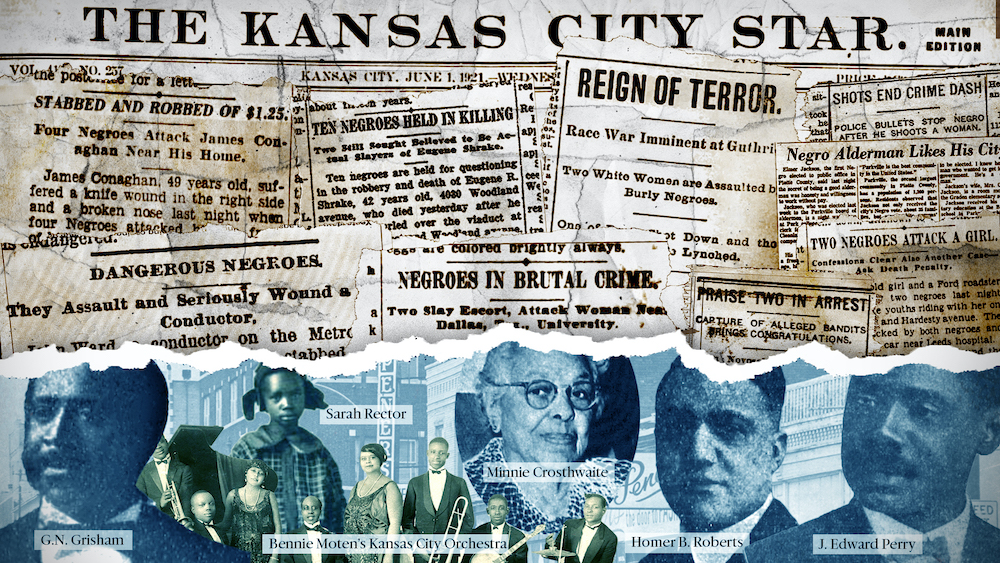

We had to admit what we did was wrong and show readers exactly how we failed with a series of stories exposing the racist language and racist slants that had filled our pages as far back as the 1800s when The Star and its sister paper, The Kansas City Times, began. It would mean months of research, including examining stacks of court records and hundreds of archived papers, digitized and on microfilm. It would require identifying, locating, and interviewing Black Kansas Citians who were the subject of some of the incidents about which we wrote.

We began with a focus group of longtime community leaders and got their takes on what we hoped to do. Black residents, they said, don’t trust the mainstream newspaper because they see nothing in it that tells their story. For decades the only time they saw themselves in our pages was as perpetrators or victims of crime. In Kansas City, Black residents read The Call, a weekly Black-owned paper.

Star leadership realized this project meant we would open ourselves to community scrutiny of everything we might do related to race going forward, not just in our coverage but in hiring and community engagement as well. “Let’s do it,” said Mike Fannin, The Star’s president and editor.

Reporters, photographers, and editors were tapped for ideas on what historic moments should be reviewed to gauge how or if The Star had included Black citizens in its coverage. The entire staff recognized this project would not stop at publication. It would be an ongoing effort involving every one of them.

This project was meant to reveal a wrong and provoke community and industry change. We hoped other news operations nationally and businesses and agencies locally would also look inward and make amends. But more importantly, we hoped it would change the way we ourselves do business.

Reporters were eager to get on board. It just so happens we took on this project during one of the busiest news years ever. To make it work, for about seven months, the four reporters researching and writing the stories were given time for the project on rotation — two weeks on daily news followed by two weeks on the project.

While reporters worked, guided by supervising editors, top editors hired the paper’s first ever race and equity editor and began putting together an advisory group that would eventually work with staff to identify stories and issues of impact to minority communities in Kansas City. The project — “The Truth in Black and White” — published on December 20 as a front-page apology from Fannin followed by six stories about The Star’s failures:

“As floodwater upended Black lives, Kansas City newspapers fixated on Plaza, suburbs.”

“Charlie Parker? Jackie Robinson? For The Star, Kansas City Black culture was invisible.”

“When civil rights movement marched forward, The Kansas City Star lagged behind.”

“‘Brutes’ and murderers: Black people overlooked in K.C. coverage — except for crime.”

“Kansas City schools broke federal desegregation law for decades. The Star stayed quiet.”

“J.C. Nichols’ white-only neighborhoods, boosted by Star’s founder, leave indelible mark.”

The lion’s share of the reader response was from people thanking and praising the paper. Others called it performance and wanted to know what real change would come of it. Would The Star hire more people of color and write more positive stories about people of color and the communities where they live?

Yes and yes.

We also have started a ‘news in education’ effort with city public schools and launched a series of virtual events with the public library to connect with the community.

But the real change is what happened when my colleagues and I discovered the depth of racism that had existed. Discovered that until his death in 1955, The Star hadn’t written about native son and famed jazz musician Charlie Parker. And that when four Black men, and possibly two others, were shot by police during a 1968 civil rights protest, The Star painted unflattering portraits of each of them, including a 16-year-old boy whom the paper described as not a good student. The Star, when writing about Black school children, who as late as 1977 were segregated from white students in public schools, referred to them as “a problem.”

For decades when Black people were written about, if it wasn’t about crime stories, it tended to be belittling and mocking. The Star almost never ran photos of Black residents, and too often talked about Black people, not to them.

More than once during the research I wept. The project stirred my and my colleagues’ journalist souls.

We will approach every story we write differently. We will question our intentions, use of language, placement of stories and decisions about what we cover and what we don’t. Doing this project changed the way each of us does day-to-day journalism.

Mará Rose Williams is an education writer for The Kansas City Star, where she has worked for more than 20 years.