President Trump may be leaving office but he and his rhetoric about fake news are here to stay. From the beginning of his presidential campaign, Trump has used the rubric “fake news” to demean and harass journalists; his administration has furthered this work by placing restrictions on how journalists operate. Trump’s attacks on journalists have been amplified by right-wing media and other members of the Republican party.

Whatever happens to Trumpism, the idea of “fake news” won’t disappear.

This summer saw hundreds of freedom of the press violations as journalists were attacked with rubber bullets and pepper spray while reporting on protests for racial justice. In the fall, the Department of Homeland Security proposed changing the visas given to foreign journalists to reduce their time in the United States from five years to 240 days, with an option to renew for another 240 days. Months before that, the Trump-appointed head of the U.S. Agency for Global Media, which includes the Voice of America news outlet, dismissed the leaders of several networks and replaced them with loyalists who share his conservative views.

Trump has also given autocrats around the world cover and inspiration for their own “fake news” campaigns. Those autocrats will continue to feel empowered even after Trump is out of office. To better understand how journalists facing this difficult environment might work and adapt, we looked to four countries where the mantle of “fake news” is used to intimidate and threaten. Here’s how journalists are responding to threats.

Trump has given autocrats around the world cover and inspiration for their own “fake news” campaigns

Belarus

“Before the summer, it was totally safe to be a journalist in Belarus,” says Anton Trafimovich, a reporter with Radio Free Europe in Minsk. Arrests of independent journalists were common, but reporters felt they could still do their work. But ever since a contested election was called in favor of longtime dictatorial president Aleksandr G. Lukashenko, the situation has gotten far more violent. Journalists have regularly been shot with rubber bullets and have been hospitalized; Trafimovich himself was beaten and his nose was broken.

He recently went to pick up a journalist friend who had been detained for 15 days in a jail several hours outside of Minsk. Because of the number of arrests of journalists and activists, he says, “there is not enough space for detainees in Minsk.”

The charged environment comes out of the run-up to the 2020 election. The candidate for the opposition, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, found greater popularity among Belarusian voters than expected. When exit polls showed Lukashenko — who has ruled the country for the 26 years since its independence — at 80% of the vote, protests erupted around the country. They were quickly followed by a brutal police and military response.

The arrests and violence have pushed journalists to work in new ways. Journalists no longer wear clothing identifying them as press for fear of being targeted. The violence also has prompted a change in news distribution: Media outlets have migrated onto the messaging platform Telegram.

As Valerie Ulasique, a Belarusian video journalist currently based in Poland, explains, many of the Telegram channels receive crowdsourced material and then distribute items that they can fact-check. Some of the most popular channels are run by activists, like longtime blogger Anton Matolka, whose channel has over 100,000 subscribers, according to Ulasique. But more traditional outlets like Radio Free Europe also distribute their material on Telegram. According to Trafimovich, “all media are [now] Telegram channels and that’s it.”

The majority of reports distributed on Telegram are simply short sentences, photos, and videos of protests, as well as coverage of ongoing police brutality. “The visual content is extremely important,” says Trafimovich. Content is more likely to be sent now by ordinary Belarusians, who, says Trafimovich, wish to help the media in their coverage. Because police tend to attack people with professional equipment, both journalists and citizens have taken to filming on phones. Communicating via Telegram also helps journalists get around regular internet shutdowns.

Lukashenko has regularly called reports about his reign “fake news.” But the length of the protests, and the way the mainstream media have covered them, have weakened Lukashenko’s power, according to Trafimovich. “People don’t trust state media and don’t trust Lukashenko,” he says. “The media don’t quote him as much as before because there are new speakers. He is not the agenda setter anymore.” In the meantime, Trafimovich highlights that the increase in user-generated content not only expands people’s understanding of the protests, but helps journalists report and stay safe.

Jordan

Special pieces of legislation in Jordan allow for prosecution whenever any government authority is uncomfortable, explains Sara Kayyali, a researcher at Human Rights Watch. There are the laws that criminalize talking poorly about the king, country, and allies of Jordan. In August, a cartoonist was detained by Jordanian police for having drawn a cartoon satirizing the peace deal between the United Arab Emirates, an ally, and Israel. The cartoon showed a sheikh being spat on by a dove imprinted with the Israeli flag. This spring, restrictions put in place during the coronavirus pandemic threatened jail time for “causing panic” about the virus; a number of media executives and journalists have been detained on these grounds.

Since a wave of anti-terror measures were put into place in 2015, crackdowns on the free press in Jordan have become steadily harsher. This has led to greater self-censorship among journalists. Many local journalists no longer wish to cover potentially controversial topics. “This year there were widespread teacher protests. The government disbanded their union and arrested their senior members,” explains Taylor Luck, a correspondent for The Christian Science Monitor who is based in Jordan. While he feels some sense of protection as an American journalist working abroad, “not a single Jordanian reporter reported on it.”

Luck explains that the new restrictions have made him “much more protective of sources.” He makes clear to sources the possible ramifications of speaking with a journalist. But it’s “burdensome and takes up a lot more time.” The red lines are being drawn not only about issues in Jordan but about reporting that has to do with the country’s allies, like Saudi Arabia. He cited the construction of a new “smart city” in Saudi Arabia, a pet project of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman that has forced the evictions of members of the Huwaitat tribe as an example of the kind of topic that is more difficult to write about. “It's a second job managing this and navigating these invisible red lines,” he says. “Which are the hills that I’m ready to die on?”

Rana Husseini, a journalist who has focused on women’s issues over the course of a nearly 30-year career, says that self-censorship is now a powerful force among Jordanian journalists. “I feel more recently that we are less at liberty to talk about many things,” she says. As a result, there are stories that she doesn’t even pursue. “We had a case a few months ago where a woman was hit by her father [and she subsequently died]. People were really outraged and started to write about it.” But when the prosecutor’s office published a statement saying that ongoing cases could not be publicly discussed, the articles dried up.

While the effect of this censorship makes daily reporting more difficult, Luck points to the ways in which it has changed the media landscape. More people are sharing news in closed Facebook and WhatsApp groups. His articles get translated and passed around, he says. And instead of strengthening the voice of the government, censorship may be weakening it. “State news and media have lost legitimacy,” he says.

Thailand

Freedom of the press has long been limited in Thailand, but reporting has become more challenging over the last few years. As criticism of both the royal family and new military rule has increased, so have prosecutions under the country’s strict lèse-majesté (forbidding the insulting of the monarchy) and cyber-crime laws. “When it comes to important matters, we cannot have conversations,” says Noppatjak Attanon, editor of workpointTODAY, an online news site. In 2019, the government created an “anti-fake news” center that would be staffed by around 30 people to target online content critical of the regime.

In the years following a military coup in 2014, prosecutions under these laws have increased. Activists and journalists have been arrested for their work, for Facebook posts, even for liking content online. The wave of repression has created a new set of news media, according to Daniel Bastard, a researcher at Reporters Without Borders. Sites like the Isaan Record, created in 2011, are more likely to publish articles critical of Thailand’s royal family.

At the Isaan Record, editor Hathairat Phaholtap was recently able to interview pro-democracy lawyer and activist Anon Nampa about his hopes to reform the monarchy, something Phaholtap says would not have been possible in her earlier job as a television news journalist at Thai PBS. “They wouldn’t let me interview that person or publish questions that criticize the monarchy, or criticize the king,” she says.

The site, which has a staff of six, has been monitored by the authorities, and has been visited by the police. Still, Phaholtap says that it is worth it to be able to do stories she really wants to do. Despite the enormous protests that have filled city streets, mainstream outlets “don't talk about why the student movement [exists] or how to reform the monarchy,” she says. Audiences now look to “alternative media platforms” like hers in order to find news that corresponds to the reality of the political situation. She is careful to use encrypted messaging services and has increased her security on social media, processes which are “not fun” but help her complete her work more safely.

These new media discuss the protests in greater detail and are especially sought out by younger readers who wish to follow pro-democracy movements. Older viewers are more likely to watch television news, which is carefully controlled by the government. Online news contains a greater proportion of “what people actually want to talk about,” says Noppatjak — among other things, social problems. This creates “a problem with political atmosphere. When people consume different things, they see things differently,” says Noppatjak.

Hathairat recalls that when working at Thai PBS she had wanted to do a story on Foo Foo, the lavishly-treated dog of the former Crown Prince. She was not allowed to do so. But a new generation online, she says, doesn’t feel scared. “I try to forget working under the military rules,” she says.

Nicaragua

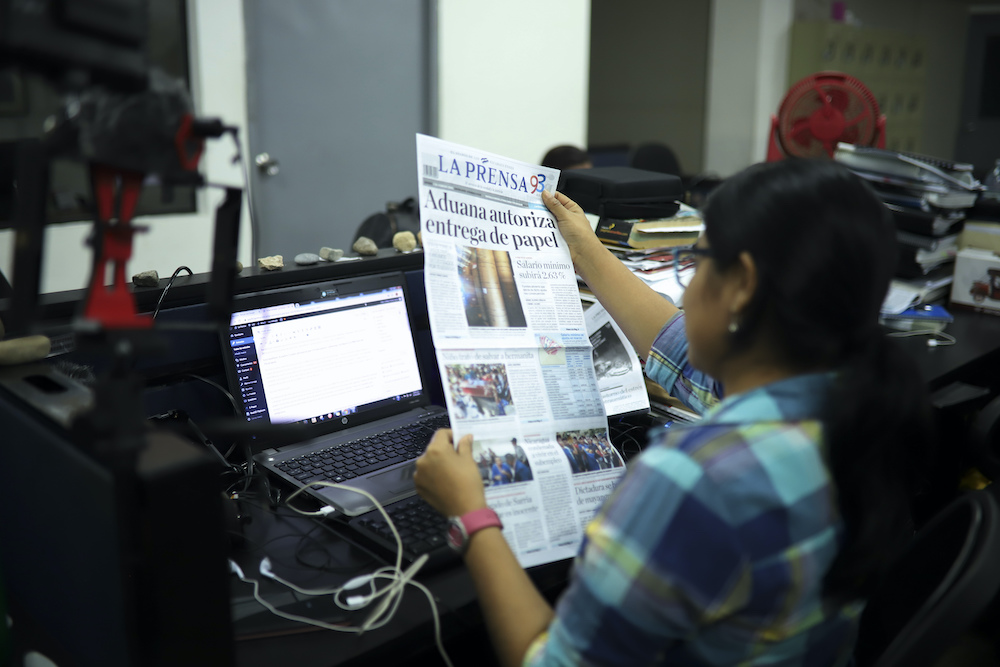

This fall, lawmakers in Nicaragua approved two new pieces of legislation. The first would require anyone receiving payment from outside the country to register as a foreign agent. The second criminalized “fake news," calling for four to six years in prison for anyone who causes “fear, anxiety, or alarm in the population,” but operating essentially as a gag order. Combined, the two laws make life for the country's journalists — many of whom have already suffered repression and are in exile — even more difficult.

Since 2018, the country’s longstanding president Daniel Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo, who serves as both vice president and de facto press secretary, have focused on cracking down on any form of opposition or criticism. “They say, ‘Well, now we are going to determine what is false information,’” says Carlos Chamorro, the founder and editor of the news site Confidencial. “That’s not going to change the way in which we work.”

Chamorro’s newsroom was occupied by police in 2019; he went into exile and only recently returned. Many other reporters remain abroad, including Lucia Pineda, a journalist arrested and held in prison for six months in 2019 under trumped-up charges, who now runs her site 100% Noticias from Costa Rica with a reduced staff, many of whom are also in exile.

Whether inside the country or outside, the pressures of the regime have forced journalists to take a more collaborative approach. Ever since dangerous repression began in 2018, journalists have taken the habit of covering unrest in pools. “No reporter is able to cover any protest under police or paramilitary harassment alone,” says Chamorro.

Instead, journalists team up to ensure they are never caught in a dangerous situation alone. Journalists fear being attacked and beaten. “You never know when you'll run into a fanatic,” says Maynor Salazar, an investigative journalist who works at a new site called Divergentes. The Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation, which advocates for the press in the country, counts 72 attacks this year alone. Working in pools allows journalists to collect firsthand testimonials, important in a country with little reliable data collection.

The sense of collaboration extends to distribution as well. Chamorro explains that there is a "network of collaborative support among the Nicaraguan media to expand the scope of distribution.” Local radio stations and media outlets share information that may have been repressed or ignored by mainstream outlets. This has allowed Confidencial to share some of its ground-breaking work in the past few months, including an investigation into the real numbers of Covid deaths in the country. Meanwhile, as the government has made little mention of the hurricanes battering the country, journalists like Salazar have been going out in pools to document its real damage. “We are filling a gap,” he says.