I was sent to Mississippi to cover Hurricane Katrina’s aftermath after The Miami Herald’s sister paper, The Sun Herald in Biloxi, found itself shorthanded. Many of the paper’s employees had just lost their homes, some were missing, and the area was in chaos. On my way there, editors diverted me to Pensacola, Florida, when they learned there might be room on a U.S. Customs and Border Protection chopper flight to New Orleans. Customs pilots were ferrying Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) officials, engineers, supplies and others to assess damage in the area. We could get on a flight if there was an empty seat, so I ended up waiting two days before finally taking off on a Saturday morning.

As we stopped to refuel in Mobile, Alabama, the pilots got word that a helicopter had been fired on that morning. Jan Makiewicz, an aviation enforcement officer, put on a bulletproof vest and placed what looked like a rifle case behind his seat. There were so many helicopters taking off and landing that the pilots asked me to point out any that I saw to them. They seemed to pop out of nowhere, below us, beside us, in front of us. I’d never seen so much chopper traffic in such a small area. “This isn’t as bad as it has been,” one of them told me.

Flying from Florida’s Panhandle region to New Orleans allowed me to see the extent of damage all along the Gulf Coast. I could see New Orleans under water—dilapidated wooden houses, elegant mansions, tall office buildings, and the Superdome immersed in a lake of brownish green goo. From above, it seemed nothing had escaped Katrina’s destructive power. Part of the Superdome’s roof had blown off, and rows and rows of people were visible, though almost swallowed by piles and piles of trash.

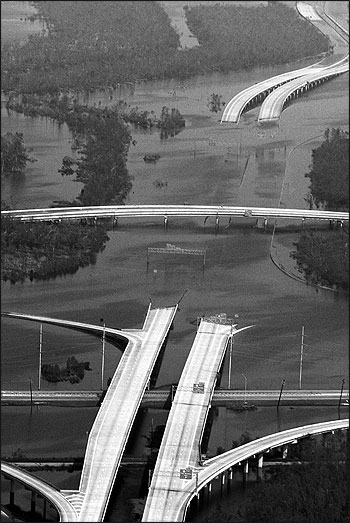

Big concrete highways sloped below the water only to pop back up again yards away. About 100 school buses sat still in water that lapped up their sides. Only their tops poked out like giant yellow turtles sitting in the murky soup. I photographed them because they looked so pretty compared to the ugly sludge around them. Later I’d read about how the buses could have been used to evacuate many of the poor and elderly who had no other way out of New Orleans. Now they sat empty and unusable.

We flew over towns in Mississippi with names like Waveland, Pass Christian, Bay St. Louis, and Long Beach. The coast’s beaches were wiped clean as though a giant hand had swept across a game board scattering its pieces and leaving gray slabs of nothingness. A few blocks inland, homes and buildings were reduced to wooden piles resembling stacks of broken matchsticks. At times I felt like I was looking down on black and white photographs of Hiroshima after the bomb fell. But these images were real, in color, and in America.

There was so much destruction that I couldn’t put down my camera. I kept shooting even though I knew that if I didn’t look up now and then to scan the horizon I’d be airsick. However, each bank of the chopper revealed more devastation, more than I’d seen in my career as a photojournalist. I’d been to Mexico City for the earthquake of 1985, seen the town of Armero, Colombia buried by mud, and witnessed the destruction of hurricanes Charley and Frances and Jeanne. What I’d never seen was devastation as vast as this, stretching on and on for hundreds of miles through several states. I shot for so long that the pilots had to set down at a small airstrip so I could clear my head and pick up an airsick bag.

One apartment complex caught my eye because you could see the progression of damage in each of its buildings. Closest to the beach, only slabs remained. A few yards back, structures were partially destroyed. Undamaged apartments were at the furthest distance from the ocean. I showed my photographs to several people to see if they could tell me where the apartments were located. “Where is this?” I’d ask, “I want to go to that complex.”

By coincidence a few days later, I teamed up with the City of Miami Urban Search and Rescue team as it worked in Long Beach, Mississippi. We ended up at an apartment complex that looked identical to what I’d photographed from the air. Rescuers worked throughout the day in over 95-degree heat stopping now and then to sniff the air. Once they pinpointed where a rotten stench came from, heavy machinery was called in to lift up the boards. Twice they found refrigerators full of rotting meat. Still the workers continued climbing and searching debris fields of two-by-fours that rose up 20 feet in some places. At one point, feeling overcome by the heat, I sat in my air-conditioned car for about an hour while I transmitted photos. The search and rescue team paused for only 30 minutes to eat.

I talked with hurricane survivors in Mississippi who described walls of water coming over their homes. Four adults had to pull eight children through windows and ferry them through the ocean that had swept through their house during the raging storm. A national guardswoman watched as water flowed onto the balcony of her apartment, the one I had visited with search and rescue workers. She was forced to swim to a nearby apartment where she spent five hours huddled on a porch as Katrina’s winds raged. Her building was now a concrete slab. At a police station, many officers clung to trees as water drowned their building. They called out to each other through the storm to make sure their comrades were alive.

Stories That Were Not Told

But stories like these were mostly ignored by the national media. New Orleans suffered catastrophic damage, but what Mississippians experienced was horrible, too, and has left scars on people and communities. While working out of Biloxi for a week, I saw only one television crew and a few print reporters and photographers, but never did I see any in the damaged areas. Last year Punta Gorda in Florida became a household name in the wake of Hurricane Charley, but very few people are aware of the devastation that is Bay St. Louis, Diamondhead, Long Beach, Waveland, Pass Christian. The video images that I saw played over and over again were of Biloxi’s casino bars washed ashore.

Given what I saw, I left Mississippi feeling disappointed by the inability of the press to tell a more complete story of Katrina’s destructive consequences and to share it with a wider audience. New Orleans didn’t deserve less coverage, but Mississippi deserved more, much more, and by our inattention there, we failed.

Were media outlets too overwhelmed by the chaos in New Orleans to look beyond that city? Was there so much to cover there that stations and newspapers didn’t have the resources—the newsroom budget or reporting staff—to send crews to Mississippi or Alabama? Was it because the burial of a major metropolitan city is a more dramatic and “sexy” story than those that could be told in washed-away, small rural towns?

It became hard for me to understand how news organizations could ignore the tsunami-like destruction in these areas. With their houses demolished, people wondered whether to leave or rebuild, to stay or to go—the same questions many in New Orleans were asking except, in this case, few people heard them. At the same time, lasting images from the other coastal states were not of people—their loss and resolve—but of wrecked casino barges. Yet little reporting was done at ground level, where interviews with shell-shocked residents and footage of the barren coastline would have given viewers a more complete picture. While reporters rightly criticized the poor response by state and federal officials to the situation in New Orleans, they also irresponsibly transmitted stories from there about murder and mayhem, rumors that later would prove untrue. In doing so we, as journalists, showed our hypocrisy in criticizing others for their efforts while not being as willing to look closely at the sloppiness of our own practice.

As I moved through small towns along the Gulf Coast, again and again people thanked me for taking their picture, even though I photographed them often at their worst—as they sobbed or swept empty concrete slabs or waded through mud-soaked buildings. “Thank you for coming,” they’d say to me. “We need the attention.” Hearing their words made me feel badly, too, since I didn’t know if the photographs I was taking of them would be picked up on Knight Ridder’s wire service or even go out to local subscribers of The Sun Herald in Biloxi. In some ways, to them, it didn’t seem to matter. “We just want people to know what happened here,” one person said, as he reached out to shake my hand.

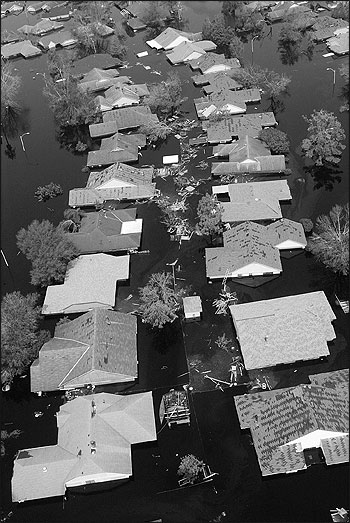

This aerial view of the Mississippi coastline shows how devastating the storm surge was from Hurricane Katrina. Some survivors described a tidal wave coming over their houses. Photos by Nuri Vallbona/The Miami Herald.

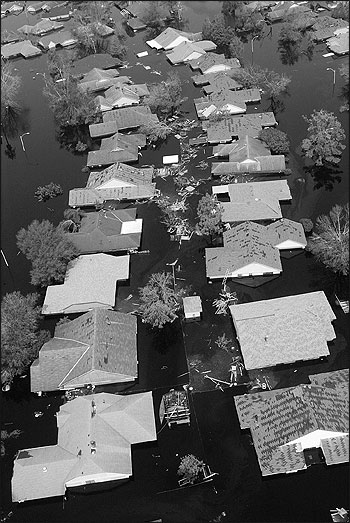

The rooftops of flooded homes in New Orleans.

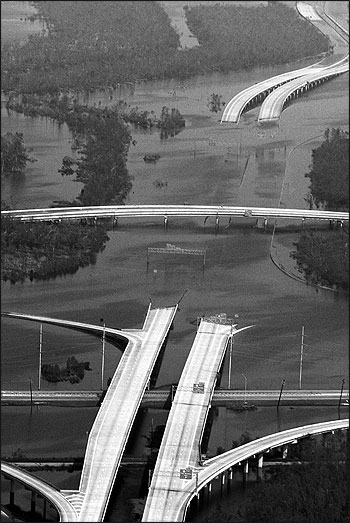

Roads outside of New Orleans sit under water after Hurricane Katrina flooded the area.

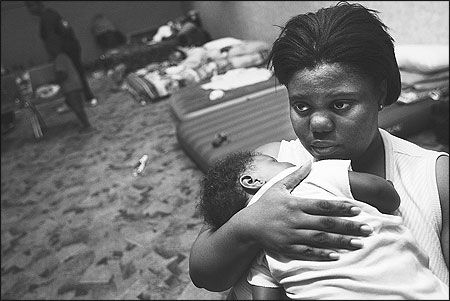

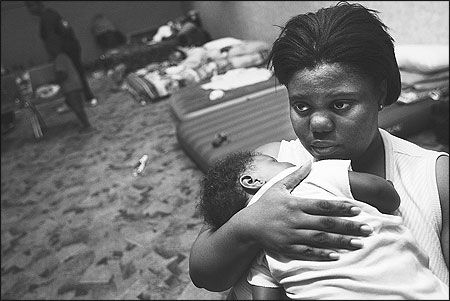

Angela Reed of New Orleans tried to calm her four-month-old daughter, Laila, while the family stayed in the Pensacola Civic Center after being displaced by Hurricane Katrina.

A neighborhood near Gulfport, Mississippi lies in ruins.

Local high school students helped to clean up Haney’s Pawn Shop before rushing off to football practice in D’Iberville, Mississippi. Pam Haney, the owner of the shop, said, “We will reopen.”

Nuri Vallbona, a 2001 Nieman Fellow, is a photojournalist with The Miami Herald.

As we stopped to refuel in Mobile, Alabama, the pilots got word that a helicopter had been fired on that morning. Jan Makiewicz, an aviation enforcement officer, put on a bulletproof vest and placed what looked like a rifle case behind his seat. There were so many helicopters taking off and landing that the pilots asked me to point out any that I saw to them. They seemed to pop out of nowhere, below us, beside us, in front of us. I’d never seen so much chopper traffic in such a small area. “This isn’t as bad as it has been,” one of them told me.

Flying from Florida’s Panhandle region to New Orleans allowed me to see the extent of damage all along the Gulf Coast. I could see New Orleans under water—dilapidated wooden houses, elegant mansions, tall office buildings, and the Superdome immersed in a lake of brownish green goo. From above, it seemed nothing had escaped Katrina’s destructive power. Part of the Superdome’s roof had blown off, and rows and rows of people were visible, though almost swallowed by piles and piles of trash.

Big concrete highways sloped below the water only to pop back up again yards away. About 100 school buses sat still in water that lapped up their sides. Only their tops poked out like giant yellow turtles sitting in the murky soup. I photographed them because they looked so pretty compared to the ugly sludge around them. Later I’d read about how the buses could have been used to evacuate many of the poor and elderly who had no other way out of New Orleans. Now they sat empty and unusable.

We flew over towns in Mississippi with names like Waveland, Pass Christian, Bay St. Louis, and Long Beach. The coast’s beaches were wiped clean as though a giant hand had swept across a game board scattering its pieces and leaving gray slabs of nothingness. A few blocks inland, homes and buildings were reduced to wooden piles resembling stacks of broken matchsticks. At times I felt like I was looking down on black and white photographs of Hiroshima after the bomb fell. But these images were real, in color, and in America.

There was so much destruction that I couldn’t put down my camera. I kept shooting even though I knew that if I didn’t look up now and then to scan the horizon I’d be airsick. However, each bank of the chopper revealed more devastation, more than I’d seen in my career as a photojournalist. I’d been to Mexico City for the earthquake of 1985, seen the town of Armero, Colombia buried by mud, and witnessed the destruction of hurricanes Charley and Frances and Jeanne. What I’d never seen was devastation as vast as this, stretching on and on for hundreds of miles through several states. I shot for so long that the pilots had to set down at a small airstrip so I could clear my head and pick up an airsick bag.

One apartment complex caught my eye because you could see the progression of damage in each of its buildings. Closest to the beach, only slabs remained. A few yards back, structures were partially destroyed. Undamaged apartments were at the furthest distance from the ocean. I showed my photographs to several people to see if they could tell me where the apartments were located. “Where is this?” I’d ask, “I want to go to that complex.”

By coincidence a few days later, I teamed up with the City of Miami Urban Search and Rescue team as it worked in Long Beach, Mississippi. We ended up at an apartment complex that looked identical to what I’d photographed from the air. Rescuers worked throughout the day in over 95-degree heat stopping now and then to sniff the air. Once they pinpointed where a rotten stench came from, heavy machinery was called in to lift up the boards. Twice they found refrigerators full of rotting meat. Still the workers continued climbing and searching debris fields of two-by-fours that rose up 20 feet in some places. At one point, feeling overcome by the heat, I sat in my air-conditioned car for about an hour while I transmitted photos. The search and rescue team paused for only 30 minutes to eat.

I talked with hurricane survivors in Mississippi who described walls of water coming over their homes. Four adults had to pull eight children through windows and ferry them through the ocean that had swept through their house during the raging storm. A national guardswoman watched as water flowed onto the balcony of her apartment, the one I had visited with search and rescue workers. She was forced to swim to a nearby apartment where she spent five hours huddled on a porch as Katrina’s winds raged. Her building was now a concrete slab. At a police station, many officers clung to trees as water drowned their building. They called out to each other through the storm to make sure their comrades were alive.

Stories That Were Not Told

But stories like these were mostly ignored by the national media. New Orleans suffered catastrophic damage, but what Mississippians experienced was horrible, too, and has left scars on people and communities. While working out of Biloxi for a week, I saw only one television crew and a few print reporters and photographers, but never did I see any in the damaged areas. Last year Punta Gorda in Florida became a household name in the wake of Hurricane Charley, but very few people are aware of the devastation that is Bay St. Louis, Diamondhead, Long Beach, Waveland, Pass Christian. The video images that I saw played over and over again were of Biloxi’s casino bars washed ashore.

Given what I saw, I left Mississippi feeling disappointed by the inability of the press to tell a more complete story of Katrina’s destructive consequences and to share it with a wider audience. New Orleans didn’t deserve less coverage, but Mississippi deserved more, much more, and by our inattention there, we failed.

Were media outlets too overwhelmed by the chaos in New Orleans to look beyond that city? Was there so much to cover there that stations and newspapers didn’t have the resources—the newsroom budget or reporting staff—to send crews to Mississippi or Alabama? Was it because the burial of a major metropolitan city is a more dramatic and “sexy” story than those that could be told in washed-away, small rural towns?

It became hard for me to understand how news organizations could ignore the tsunami-like destruction in these areas. With their houses demolished, people wondered whether to leave or rebuild, to stay or to go—the same questions many in New Orleans were asking except, in this case, few people heard them. At the same time, lasting images from the other coastal states were not of people—their loss and resolve—but of wrecked casino barges. Yet little reporting was done at ground level, where interviews with shell-shocked residents and footage of the barren coastline would have given viewers a more complete picture. While reporters rightly criticized the poor response by state and federal officials to the situation in New Orleans, they also irresponsibly transmitted stories from there about murder and mayhem, rumors that later would prove untrue. In doing so we, as journalists, showed our hypocrisy in criticizing others for their efforts while not being as willing to look closely at the sloppiness of our own practice.

As I moved through small towns along the Gulf Coast, again and again people thanked me for taking their picture, even though I photographed them often at their worst—as they sobbed or swept empty concrete slabs or waded through mud-soaked buildings. “Thank you for coming,” they’d say to me. “We need the attention.” Hearing their words made me feel badly, too, since I didn’t know if the photographs I was taking of them would be picked up on Knight Ridder’s wire service or even go out to local subscribers of The Sun Herald in Biloxi. In some ways, to them, it didn’t seem to matter. “We just want people to know what happened here,” one person said, as he reached out to shake my hand.

This aerial view of the Mississippi coastline shows how devastating the storm surge was from Hurricane Katrina. Some survivors described a tidal wave coming over their houses. Photos by Nuri Vallbona/The Miami Herald.

The rooftops of flooded homes in New Orleans.

Roads outside of New Orleans sit under water after Hurricane Katrina flooded the area.

Angela Reed of New Orleans tried to calm her four-month-old daughter, Laila, while the family stayed in the Pensacola Civic Center after being displaced by Hurricane Katrina.

A neighborhood near Gulfport, Mississippi lies in ruins.

Local high school students helped to clean up Haney’s Pawn Shop before rushing off to football practice in D’Iberville, Mississippi. Pam Haney, the owner of the shop, said, “We will reopen.”

Nuri Vallbona, a 2001 Nieman Fellow, is a photojournalist with The Miami Herald.