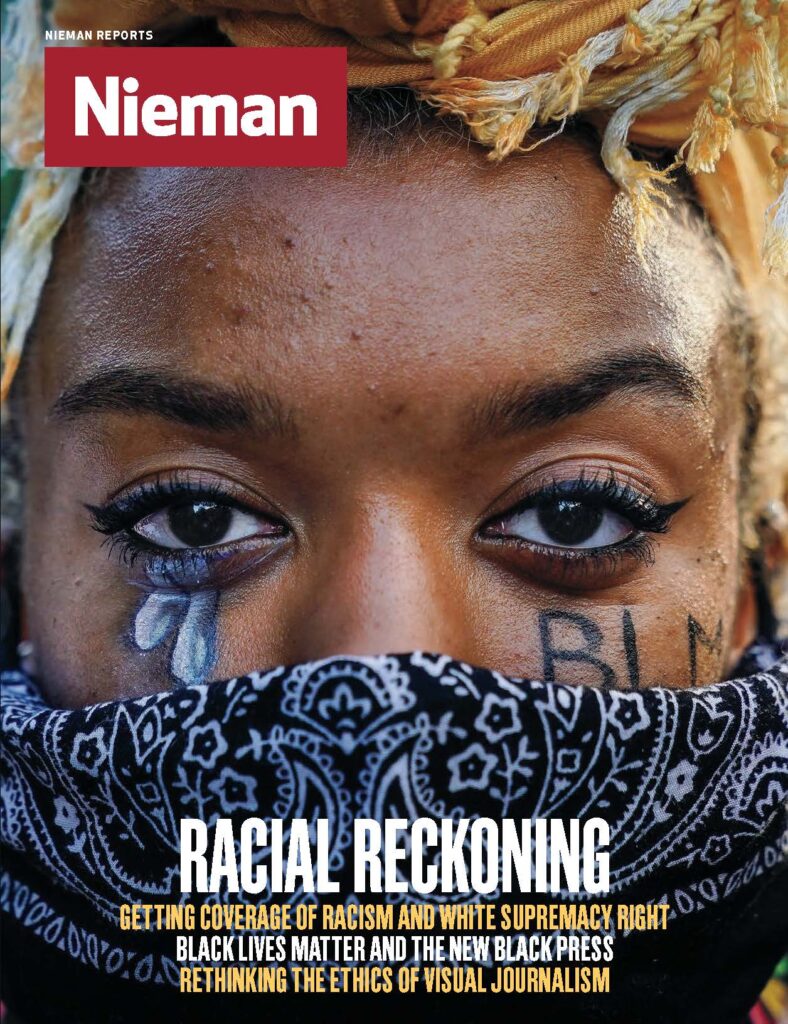

On Saturday, May 30, 23-year-old Army reservist Zaria McClinton drove to the state capitol building in Little Rock, Arkansas to take part in the city’s first large demonstration following the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. She didn’t know a single person there, but right away fell in with a small group of like-minded activists, mostly young women like herself, eager to inject some organization into the crowd’s enthusiasm.

“A lot of people’s emotions were already high,” she says, “and I’m like, ‘Okay, we’re still here at the capitol; it’s nighttime; no one sees or hears us.’ So, we need to make a bigger statement. And what better way to be heard than to stop traffic.”

As the sun went down, McClinton and a couple hundred protesters marched toward the ramp to Interstate 630, which is infamous in Little Rock. Known ominously as “the Wall,” it runs east-west through downtown. In the 1960s, a historic Black business district was paved over to build it, and still today the expressway segregates more affluent white neighborhoods to the north from Black neighborhoods to the south.

The perfect place for a Black Lives Matter rally.

At first, the authorities mostly left protesters alone, McClinton says. But by the time Paige Cushman, a digital reporter for the local ABC affiliate KATV, arrived on the scene, State Police had taken charge and begun to close in on the protesters, who were now blocking the interstate and marching through stalled traffic. “None of us until then had ever been tear-gassed,” Cushman says, “so we couldn’t confirm that it was tear gas. All we could say was that some type of crowd-dispersing something had been deployed.”

People were running from the police, Cushman says, and she was running, too. The tear gas was stifling. She found it impossible to take notes for the story she was supposed to write and panicked that she had not been tweeting about what was developing. “One of my partners on the digital team was like, ‘I don’t know how else to say what’s going on here so I’m just gonna go live on Facebook so everyone can see it,’” Cushman recalls.

And a lot of people did.

The KATV digital team often livestreams noteworthy events. “It generates a lot of traffic,” Cushman says. “It reaches sometimes an audience bigger than what we can even get going live on broadcast.” The protests, though, were the first time she had tried anything like this in the field — livestreaming, reporting, and narrating what she was seeing, all at the same time.

Little Rock is a telling case study in the changing relationship between local news outlets and the communities they cover

“Right now we are watching a tipping point,” Larry Foley, chairman of the School of Journalism at the University of Arkansas, told me by phone from Fayetteville. “There is no doubt in my mind public opinion changed over the Vietnam War because of media coverage. The same thing with the civil rights events of the ’60s … where people would just become outraged at what they saw. I think that there’s an absolute parallel to a knee on someone’s throat for eight minutes.”

The defining stories of our day — Covid-19, racism, police brutality, and the tanking economy — know no boundaries, but national and cable news networks rarely venture beyond a few major cities to tell them. Says Foley, “What are people doing when they want to know what’s going on — they’re going to the local newscast.” Local TV news viewership and ratings are high. Meredith Corp., Nexstar Media Group, Sinclair, and Gray Television have reported major increases in viewership for their stations since the start of the pandemic.

Despite the crucial role of local newsrooms in providing essential coverage, tension — between reporters and protesters, between reporters and law enforcement, between reporters and audiences — is also high, while trust is low. Americans rate local TV news as the best source — when compared to local and national newspapers, local news radio, national network and television news, and online news organizations — of coronavirus news, with 55% describing coverage as “excellent” or “good,” according to a Gallup survey. That doesn’t necessarily mean they find it all that trustworthy. Fewer than half of U.S. adults (42%) say they have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in local news organizations in their area, according to the same Gallup poll, released in May; that’s just a slight increase from 37% in 2019.

That makes Little Rock a telling case study in the changing relationship between local news outlets and the communities they cover. Local journalists, especially those working in smaller markets in Middle America, face the same attacks on their credibility as those at the national level, sometimes more so. “The vitriol that’s coming out of the president has stirred this stuff up — the ‘fake media’ and the ‘lamestream media’ and ‘fake news,’” Foley says. “It angers me because it’s a big fat lie.”

Watching the viewer comments in real-time on her screen, Cushman knew the livestream was going to have an impact. “People wanted to be there but a lot of them couldn’t be there because of Covid, or they didn’t agree with the protests or whatever, and it was such an easy way for them to just be in the middle of it,” she says. According to Cushman, her audience seemed pretty evenly split between those who saw the demonstrations as a long overdue exercise in peaceful civil disobedience and those who thought New York City-style anarchy had arrived on the streets of Little Rock. The only thing the two sides seemed to agree on: Cushman herself was a pawn manipulated by the other side.

“The first night we were out there was a lot of hostility from protesters, and it’s not just our station,” Cushman recalls. “It was every single camera crew. I had a hard time with this, trying to get on the same page with them. It’s like, We’re not on anybody’s side. We’re here to hold everyone accountable to show what’s going on.” Cushman says she tried to communicate with movement leadership directly, but there seemed to be an anti-press bias, even before a single report had been filed.

According to Quinn Foster, a protest leader and founder of Arkansas Hate Watch, the distrust of local media comes from watching how protests have been covered nationally in places like Minneapolis and New York. “Black Lives Matter has the stigma of being a catalyst of violence,” he argues, “and it’s justified through the media’s representation of criminal activities that have occurred around these protests.” Yet in Little Rock in May, June, and July, I attended dozens of protest events and witnessed very little damage or violence.

McClinton says the media plays up isolated instances of violence and destruction for ratings. She complained about a local news story in which footage of looting from another city was included in a story about her group in Little Rock: “We did an interview, but all that was seen on the television was us saying, ‘No justice, No peace’ then it cut to images of protesting and looting.”

That conflation of looting and peaceful protesting has happened in the national press, too.

"An entire day of peaceful protest reduced to a few minutes of madness on the morning news"

Little Rock was the site of what became one of the most famous events of the civil rights era. In 1957, President Eisenhower sent federal troops, the 101st Airborne Division, to stand down white racist mobs and the National Guard that had been called out by Governor Orval Faubus to stop nine Black teenagers from integrating Central High School. With the protection of the military, the Little Rock Nine were able to finally attend school, but the next year rather than comply with the desegregation mandate the county simply cancelled the high school year for everyone. Today, on the side of the capitol building where most of the protests have been taking place, stands a monument to the nine brave teenagers who integrated Central High School; nearby, on the front lawn of the capitol, are two monuments to the Confederacy.

In a June 3 New York Times op-ed, Arkansas Republican Senator Tom Cotton cited Eisenhower’s decision as a precedent President Trump could use to employ the Insurrection Act against Black Lives Matter protesters around the country. The op-ed generated outrage among journalists in The New York Times newsroom and elsewhere; some argued that Cotton’s comparison of white racist mobs with peaceful Black Lives Matter supporters stoked racial violence. The editor of the Times’s opinion section eventually resigned.

“So much of my thought right now, it goes back to the Central days where I kept thinking, ‘Can’t these people think?’” says Minnijean Brown-Trickey, one of the Little Rock Nine. Trickey, speaking by phone from her home in Vancouver, called Cotton’s words “dangerous” and “disgusting” but stopped short of saying the Times should not have run them. “I try to get people to talk their truth because other people need to hear it. Let us see it. Let us see Arkansas going backwards again.” She adds, “When you have a profound intentional ignorance in a society, you can say anything you want because they don’t know how to question you because American history is such a fairy tale and skewed towards non-truth.”

Despite being roughly 42% Black, only in 2018 did the city of Little Rock elect its first African-American mayor, a pastor and former banker named Frank Scott Jr. The morning after the I-630 protest, he addressed the city’s first intense encounter with a Black Lives Matter protest: “We have to understand that we have people in a city, in a land, that are experiencing hurt, heartache, and pain. … For those who don’t understand and may be a critic to what happened last night … take time to listen and to learn.”

“In that moment, I was leading with my heart,” Mayor Scott told me later about that press conference, in which he twice emphasized that it was “other agencies,” not the Little Rock police, that used tear gas against the protesters.

“In this day and age, you have media representatives that are committed to the free press, committed to fair and impartial news,” Scott said of press coverage, “but sometimes you begin to question the intent when only certain perspectives are shared. And I think the millennial generation … will call those to task when they see any type of discrepancy.”

On Sunday, May 31, Scott continued to give protesters an extraordinary amount of autonomy to gather and march, largely unimpeded by law enforcement. I stood with hundreds of protesters on the steps of the capitol building and listened to them chant, “Prosecute the police!” without a uniformed officer close enough to even hear it. There was so much landscape between the protesters and Little Rock police that one driver was doing donuts in the middle of the road as news crews scrambled to go live, his car spinning wildly in the background.

For McClinton, that was more evidence of biased coverage — an entire day of peaceful protest reduced to a few minutes of madness on the morning news. “I feel like it is a trend,” McClinton says, referring to what she feels is a tendency for reporters to seek out images of rowdy behavior at protests. “The rioting and the looting that was going on across the nation, for us we really didn’t have a lot of that going on here.”

McClinton is correct. Governor Hutchinson cited a fire and a burglary for his decision to send in riot police later that night. But I was present for both incidents, and they were minor. The burglary, for example, occurred when a rogue protester pulled a piece of plywood off the door of a government office and scattered some papers around. The crowd turned on him immediately, picked up all of the debris, and resealed the door themselves.

Cushman was there livestreaming for KATV. When one protester saw that, he began following her around all week, disrupting her feed and yelling in the background, “She’s the media! She’s the media!”

“It’s such a broad generalization to just say, like, fake news, media is bad, you’re provoking this or you’re fueling the fire,” Cushman says, “because, like, all of us have different experiences, different backgrounds, different education and, like, a lot of us are there for different reasons.” Still, she understands the power the media has and not all the reporting is good: “We absolutely do have the ability to completely, you know, dismantle what they’re trying to achieve. And we also have the ability to send them to jail, so I kind of don’t blame them for not being super-stoked about us.”

At one point during the night of June 1, things did briefly get out of hand. After Mayor Scott tried and failed to get protesters to observe a 10 p.m. curfew, the windows of a number of bank buildings were smashed, a guy tried to steal an ATM machine by hooking it up to a pickup truck, and fireworks were shot at police officers. I was there (I wasn’t wearing press identification, since as a freelancer I don’t have one issued to me by a news organization) and had just photographed a guy throwing a brick through the window of Bank OZK; he smiled at me and went about what he was doing.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reporter Tony Holt wasn’t so lucky. He waited for the crowd to pass by him and walked over to the shattered entryway to the bank building, took a photo on his phone of the damage, and started to tweet. There were no protesters in the shot he took. Then he heard someone yell, “There is the snitch!”

One guy took his notebook and ran away, while another one knocked him out with a brick. I saw him being carried away to safety by protesters, blood running down his face. He tweeted out a selfie, his eye swollen shut and his nose broken: “I have no memory of the attack last night in Little Rock, but there was a small group among the rioters who clearly didn’t want me there.”

Holt thought he might have gotten too close to the action and provoked the guys who had done some of the damage to attack him. There is a real tension in the streets, with some worried they will get caught on camera damaging property and others worried that journalists will reduce the protesters’ message to looting. “I’m worried that it could happen many more times,” Holt says, “and I’m surprised it hasn’t happened more often now.”

In response to criticism from McClinton and others that local media doesn’t treat them fairly, he feels, in contrast, that many journalists are not being critical enough: “I understand the empathy they have for the protest and what happened to George Floyd. But there have been people who have behaved stupidly and terribly during all this, and they should be called out like anyone else. And I haven’t seen much of that locally or nationally.”

The media coverage of that night, focused on the property damage, prompted McClinton to urge protesters to stop speaking to TV reporters, a stance echoed by Trickey. “Media is not to be trusted. It can’t be,” she says, in part because of the lack of historical context in reporting: “Not making reference to the kinds of destruction that have been done to Black communities, you know, really brutal horrific violence. I really worry how the destruction of property gets to be more important than the destruction of life.”

"I’m sure it was startling to some people to see that photo in their newspaper"

A few days after he was attacked, Holt says he got an email from the managing editor at the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Eliza Gaines. The paper wanted to run a full-color in-house ad featuring the photo he uploaded to Twitter showing his bruised face and broken nose. “We believe someone knew that he was a journalist because his reporter’s notebook was taken from his pocket and then he was struck,” Gaines says. On June 4, the ad ran on page 8a with the headline, “This is the face of journalism,” and this text below the picture: “The support of subscribers is crucial and essential to keep reporting the news impartially, without fear or favor.”

Like most small papers, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette has struggled to keep its head above water. It has also received attention for moves it’s made to stay relevant and solvent — putting up a paywall early on, going digital except for Sundays, passing out iPads to subscribers. “I’m sure it was startling to some people to see that photo in their newspaper,” she says, “but I think it was an effective way to show that we give them the most complete story, and that our journalists are risking their safety to do their job.” I asked Gaines if she was concerned that running the ad of Holt’s bloody face might inadvertently send the message to readers that the Black Lives Matters protests are unusually violent. “That never crossed my mind,” she says. “Just give everybody the straight news. And let them decide whatever they want to.”

Little Rock is a one-daily town, and it is not impossible to imagine it as one day having none. Holt says the image of his battered face in an ad maybe “would give [residents] an incentive to appreciate more what we do. And maybe that would generate some extra subscriptions or re-subscriptions.”

Late on the night of June 2, the National Guard and state police and other agencies working together under a unified command made 79 arrests after an act of vandalism. Cushman was livestreaming when police started rounding up protesters by the dozens. The group she was with was corralled onto a footbridge near the river. “I did consider stopping” livestreaming, Cushman says. “And then I was like, 'What purpose does that serve?' The whole point of me being here is to show what these protesters and what these law enforcement agents are going through.”

Cushman’s video shows two state troopers pacing back and forth through a group of mostly young people of color. There is also an officer or guardsman dressed in camouflage and battle gear. For almost 10 minutes she continues to roll and narrate what she sees. She identifies herself to the state troopers: “You have two TV reporters; we have told you that multiple times.”

The trooper leans in to look at her press pass and says, “I don’t know you.”

“I talked to you right down there and told you we were press,” Cushman replies to the trooper. “Under the curfew guidelines we’re allowed to be working.”

She keeps the video rolling as a protester turns and asks an officer what he is being arrested for; Cushman reports: “He said they are under arrest for violating curfew and whatever else they could think of.”

Eventually one of the state troopers gets word that he is live on KATV telling a protester they will likely face trumped-up charges — eventually more than 270,000 people will watch the video — and tells Cushman and her partner they are free to go.

“That made me really angry to know I had been with these protesters all evening, and none of the people on that bridge from what I could tell were the people who had been throwing water bottles,” Cushman says. “It was about accountability at that point. I didn’t really care how many people were watching.”