In Weare, New Hampshire, a small town about 45 minutes from the state’s southern border with Massachusetts, the local newspaper is largely a one-man show. Michael Sullivan is de facto publisher and editor in chief as well as reporter, layout designer, crosswords creator, printer, and deliveryman. (The one thing he doesn’t do is photography.)

But Sullivan is quick to tell anyone who asks: he’s no journalist. Rather, he’s a librarian—just one who happens to run the only publication dedicated to covering his town and its 8,966 residents.

Sullivan is director of the Weare Public Library, where he—with some help from his fellow librarians—produces Weare in the World, a weekly publication that aims to fill part of the void left when the quarterly Weare Community News, shuttered in October 2016. “It wasn’t much of a newspaper to begin with, but when that thing closed down, it really left us with nothing,” says Sullivan. “The regional papers around here don’t pay attention to a little town like this, and the one local paper [The Goffstown News, a small weekly serving communities northwest of Manchester] that was covering us pulled back and stopped covering our area. We were left with no news outlets at all.”

A few months later, during Weare’s March Town Meeting season, locals were complaining that there wasn’t enough information to help them make decisions when electing local officials and passing budgets. That’s when, at a community meeting hosted at the library, one of the candidates running for town selectman turned to Sullivan and asked him what he, as town librarian, was going to do about it.

A week later, the first issue of Weare in the World appeared, providing election results alongside calendar listings for the Weare Middle School’s production of “Roald Dahl’s Willy Wonka, the Musical” and a community spaghetti dinner at the local American Legion post.

Since then, the print publication—also posted weekly on the library’s website—has remained heavy on calendar listings and events coverage, but aims to keep the town informed about local politics as well as goings-on in the community. Sullivan considers stepping in when a local news outlet is missing part of the public library’s duties to serve its patrons: “We’re here. It’s not everything you want, but it fills a need. That’s really where libraries should be.”

Increasingly, libraries are playing a greater role in journalism, as journalists and librarians—long entwined by common goals, and facing similar challenges as their industries undergo rapid transformation in the digital age—find ways to collaborate. Some librarians help where news organizations are absent, in news deserts such as Weare, or have been decimated in recent years, such as in Longmont, Colorado, where locals are debating whether to launch a tax-funded “library district” that produces community news alongside operating the local library. Other librarians are teaming up with journalists to promote media literacy and tackle misinformation, develop community journalists, spur civic engagement, and even to take on reporting projects.

Long gone at most news outlets are the days of morgues and librarians, once a mainstay at larger newspapers, magazines, and broadcasters. And yet, most librarians these days wouldn’t be completely out of their element in a newsroom, or vice versa. Many journalists would find some of a reference librarian’s primary duties not too far afield from their own research and reporting experiences. Librarians are, after all, what David Beard, writing for Poynter.org, dubbed journalists’ “information-gathering cousins.”

“Journalism and librarianship both exist to support strong, well-informed communities. We’re all working to provide reliable information in a context that makes it as useful as possible,” says Laurie Putnam, a communications consultant and lecturer at San Jose State University School of Information who often writes about the intersections between libraries and journalism. “We believe in facts. We grapple with the concept of neutrality, and we fight for equal access and intellectual freedom. We’re part of the communities we serve, and we care about keeping our democracies healthy and our citizens engaged.”

What’s more, Putnam says, libraries are often well-equipped to provide resources and manpower that news organizations, especially local outlets, may lack. “When it comes to libraries and journalism, there’s both a community need and a strategic fit. News organizations are struggling in many communities, and libraries are in a position to help. There are very real opportunities for long-term partnerships that support community information needs.”

One major reason for news organizations to partner with libraries: people trust them.

In a 2017 Pew study looking at the percentage of U.S. adults who trust information from different sources, local public libraries and librarians topped the list, with 40 percent of respondents saying they had “a lot” of trust in them. That’s compared to only 17 percent saying they had that amount of trust in national news organizations; trust in info from local news organizations wasn’t much better, with only 18 percent of respondents having a great deal of trust in them. Another Pew study published the same year found that more than 78 percent of U.S. adults feel that public libraries help them find trustworthy, reliable information (that number was even higher for millennials, at 87 percent), and more than half said that libraries help them get information to make personal decisions.

The trust factor was a motivating force behind Spaceship Media’s decision to partner with librarians when working on The Many, a dialogue journalism project that connected hundreds of women, from different backgrounds and political leanings, to discuss political and social issues in closed Facebook groups. The Many Facebook groups—which ran from February 2018 until the midterm elections—provided a jumping-off point for stories by Spaceship’s local media partners, including news outlets of different sizes and mediums in Alabama, Louisiana, New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Ohio, and Michigan; articles highlighting aspects of conversations that the project fostered were also published by Spaceship on Medium.

One major reason for news organizations to partner with libraries: people trust them

Led by Adriana García and Eve Pearlman, the Spaceship team moderated discussions among the participating women on Facebook and, when questions arose about a topic—say, then-judicial appointee Brett Kavanaugh or immigration policy in the U.S.—or conversations were at an impasse, sought to provide carefully sourced and vetted facts and figures. Called FactStacks, this non-narrative style of reporting was usually provided by the Spaceship team or journalists from media partners they worked with on past projects, but this time around, that’s where the librarians came in.

The advantages of recruiting librarians from the Birmingham Public Library in Alabama (as well as the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh for a localized spinoff group, The Many Pennsylvania) to compile FactStacks were twofold. Not only were many of the participants likely to consider information coming from librarians as more trustworthy and objective than had it come from reporters, says García, but this also freed up more time for the journalists to focus on reporting and writing stories inspired by the conversations. “We began to see that by partnering with libraries, which are far more trusted than journalists right now, we could build on their relationship with the public at large,” says García, who is director of innovation at Spaceship and served as project manager of The Many. “Librarians are a source of information that hardly anyone questions; in a world where everything has become polarizing, libraries have remained above the fray.”

When Spaceship’s moderators came across participant questions or discussion points that would benefit from further information, García copied and pasted relevant portions of the conversations into an email and sent them over to the library. At Birmingham, five librarians alternated spending a few hours or days on a topic before sending their completed FactStacks back to García (who, in turn, would copy edit and fact-check what the librarians had sent her, making sure sources represented various viewpoints) to share with the Facebook group. This was just a “natural extension of our role,” says librarian Mary Beth Newbill.

“Libraries and librarians share many of the same values and ideals of journalists,” García adds. “This is a new way for library partners to do this—to connect to journalists in a new way and to lend their expertise to supporting the civil fabric of the communities they serve.”

In Kansas City, Missouri, librarians are lending their expertise to help citizens learn more about their own locale—and about how they can track down such information themselves—through an ongoing partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. Launched last October, a project called “What’s Your KCQ?” invites locals to submit questions about their city that journalists and librarians will investigate and then, on the Star’s website, share their answers with the public. Questions don’t have to be pegged to a specific news topic or even be current; rather, they just have to be city-centric. Queries related to the city’s history and to its infrastructure, existing or long gone, are particularly popular with readers, such as “What happened to the old City Hall at 5th and Main?” and “Why does Kansas City have a ‘bridge to nowhere’?”

The Star’s relationship with the Kansas City Public Library began prior to “What’s Your KCQ?” Since the fall of 2018, a working group at the newspaper—including Mary Kate Metivier, who until recently led the “What’s Your KCQ?” project as the regional growth editor at the newspaper—had been working with the News Co/Lab, a collaborative venture based at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, on experiments to increase audience engagement and transparency. One of these was “Java with Journalists,” where Star journalists would hold listening sessions, complete with coffee and doughnuts, at several branches of the library system to ask readers in different neighborhoods, “What do you want us to cover? What stories are we missing?”

Metivier and her colleagues realized uniting with the library again for “What’s Your KCQ?” made perfect sense given their reach as well as the overlap in the two institutions’ missions: keeping Kansas Citians informed. “Our overall goal at the Star was to arm people with the facts and teach news literacy and be transparent about it. That’s a lot of what we get out of a relationship with the library,” says Metivier, who left the Star to join the Los Angeles Times as audience engagement editor in February.

In Kansas City, librarians are lending their expertise to help citizens learn more about their own locale

Seeking not just to answer readers’ questions but to show them how they arrived at those answers, “What’s Your KCQ?” keeps readers engaged throughout the whole process. Readers can choose to notify the Star if they don’t want their name published, but must give their name and contact information along with their questions—submitted on the paper’s website with help from Hearken, a startup that builds platforms to help newsrooms engage with their audiences—so reporters can follow up if further information is needed. Then, the audience votes on which questions they are most interested in seeing the answers to, and the Star and the library get to work. Queries are divided up based on who’s best outfitted to address them; the newspaper usually focuses on more present and future-focused questions, while ones about the city’s history get passed on to the library.

In one memorable example from the holiday season that piqued the interest of many readers, a resident asked what happened to the Christmas decorations—especially the giant, colorfully-lit crowns—that, starting in the 1960s, hung above the streets downtown for many years. In his answer, librarian Michael Wells featured several historic photos of Kansas City from the library’s archives and was able to shed light not just on the background of the crowns and why they were no longer displayed, but about the decline of the city’s downtown shopping district and the urban renewal that gave way to changes in the architectural environment that no longer supported such large, street-spanning adornments.

In addition to their aligning missions and skillsets, another reason librarians are ideal collaborators for journalists is that they are often well-connected with and suited to serve two wide-ranging populations: young people and minorities—groups traditional news organizations often struggle to reach. Millennials are more likely than any other adult generation to regularly visit libraries and use public library websites; according to Pew, 53 percent of Americans ages 18 to 35 visited a public library or a bookmobile in the past year (and that number is likely much higher when academic libraries are taken into consideration), compared to 45 percent or less for all older generations. According to another Pew study from 2017, millennials are the most likely of all adult generations to say libraries help them find trustworthy and reliable information, learn new things, and receive information that helps them with decision-making.

These numbers, and views on the overall usefulness of libraries, are even higher for minorities in the U.S. Hispanics and blacks are more likely than white people to report that public libraries help them find information that is trustworthy and reliable and aids decision-making. Other Pew research finds that Hispanics and African Americans, as well as lower-income Americans, are more likely to say that libraries significantly impact their lives and communities in ways that range from help in searching for jobs to offering programs to support local business development. Such programming and extra services as well as the widespread access to computers and an Internet connection likely accounts for the widespread popularity of libraries among young people and minorities compared to older white Americans.

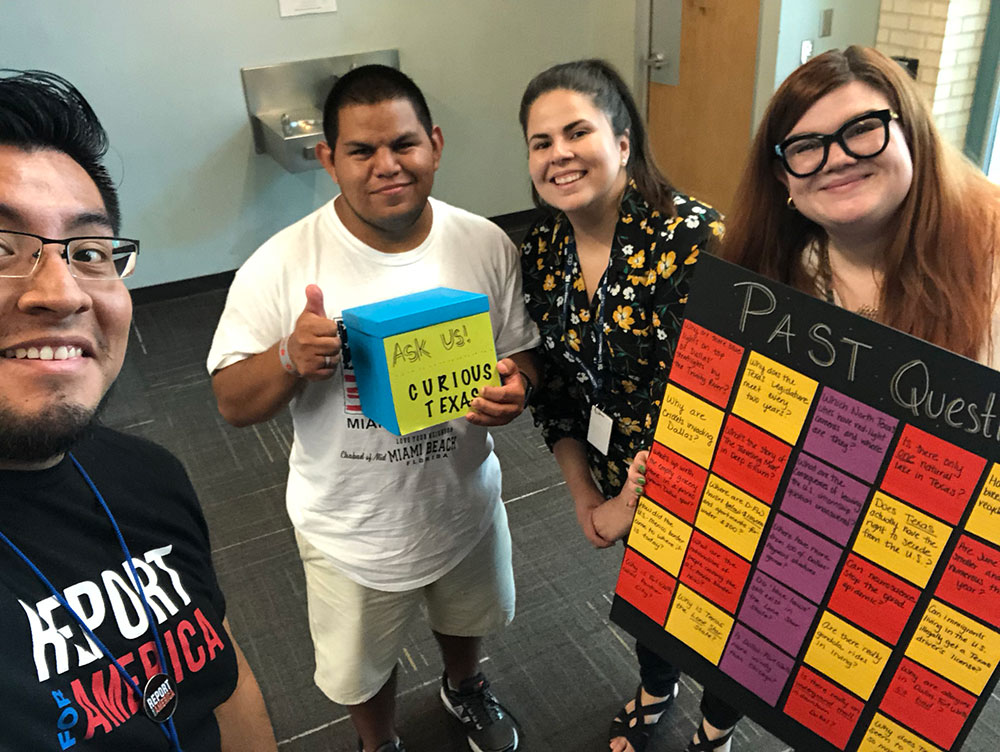

The usefulness of libraries to minority populations is a big part of the reason why, over the course of a few months in the fall of 2018, The Dallas Morning News decided to host a series of community office hours at local branches of the Dallas Public Library. Originating as part of the newspaper’s Curious Texas project, which, similar to “What’s Your KCQ?,” invites readers to submit their own questions—particularly ones about the culture and institutions of Dallas and greater North Texas—that Morning News reporters then seek to answer and share with audiences, the office hours were conceived in part to get locals involved in a reporting project. Perhaps more importantly, however, the office hours were an opportunity to have a visible presence in the community and to introduce the newspaper to new audiences.

For audience development editor Hannah Wise and engagement reporter Elvia Limón, the forces behind the office hours’ series, libraries were an obvious location to set up shop as opposed to, say, a local cafe or in the Morning News’s newsroom. For Wise, who has several librarians in her extended family, this was motivated in part by a lifelong love of libraries, but it was also a recognition of the important role libraries often play in communities, especially disadvantaged ones—something Limón had experienced firsthand.

Growing up in Pleasant Grove, a lower- to middle-income neighborhood in southeast Dallas, the local library was a valuable resource for her and her family, and a place she would spend hours hanging out and doing homework. “The library was kind of this haven—to do work with friends, [where] my mom would take classes for her GED and English language,” says Limón, adding that the library provides a similar haven—and acts as a particularly valuable resource—for Dallas’s disadvantaged populations, whether it’s homeless individuals seeking a welcome (and temperature-controlled) respite from the outdoors during the day or immigrants seeking to take citizenship and English classes. For Limón, being present at libraries “was a perfect way to reach out to people… [especially] people who wouldn’t normally be exposed to the paper.”

The usefulness of libraries to minority populations is a big part of the reason why The Dallas Morning News decided to host a series of community office hours at local branches of the Dallas Public Library

Wise and Limón focused their efforts on library branches in neighborhoods, many of them with majority Hispanic or African-American populations, that were typically underserved by the paper and other mainstream media outlets in Dallas and the surrounding area, such as Oak Cliff and South Dallas. Limón—sometimes joined by Wise or another Morning News reporter—would set up a makeshift office of sorts, complete with business cards and a box for visitors to leave comments or questions in, inside the five library branches at which they held office hours. Staffing the table for up to four hours, Limón—greeting people in both English and Spanish—had a goal to have at least 10 meaningful interactions at the first office hours, held at the North Oak Cliff branch in September. She wasn’t there to sell subscriptions or necessarily even to get story ideas; rather, she was just there to listen—whether people had questions about Dallas, the paper, or journalism in general, or even if they just wanted to share things that were going on their neighborhood that they thought deserved coverage. Complaints were welcome as well.

Wise says the office hours were an effective means for engaging with people who aren’t regular news consumers, but have the potential to be. “We would just try and have a conversation with people—it’s something my team does regularly with subscribers,” says Wise. “If we go to libraries, we can tell people, ‘Oh, you love the Rangers? We would love to hear from you. You should follow our Rangers reporter Evan Grant.’”

Though it wasn’t the point of hosting the office hours, a couple story ideas did end up coming from the efforts. When the newspaper’s Report for America fellow, Obed Manuel, joined Limón at one of the office hours at the North Oak Cliff branch, a conversation with a subscriber led to a story about Trinity River Mission, a neighborhood nonprofit providing tutoring, mentoring, scholarships, and other services to low-income students, and how the program’s scholarship fund was strained due to the success it had had getting local graduating seniors into college or vocational programs.

For Limón, the interactions she had with community members made her think just as much about what the paper is covering in underserved neighborhoods just as much as what they are missing. One of the most memorable exchanges she had was when visiting the Polk-Wisdom branch in Oak Cliff, a predominantly African-American neighborhood in southwest Dallas, on Halloween, when her office hours coincided with an afterschool program. She ended up talking to many of the program participants—kids around 8- to 12-years-old—about issues in their neighborhood they were concerned about, and what they were used to seeing on television and in the media, in the Morning News and elsewhere. Their overwhelming answer? Police brutality against African-Americans. That was a revelation for Limón, striking her that these children needed—and deserved—to see more positive news about their community along with the negative, but often necessary, coverage of violence and race relations.

That’s something the newspaper’s other collaboration with the Dallas Public Library, a program designed to train young community journalists and promote media literacy, can possibly help address. Called “Storytellers Without Borders: Activating the Next Generation of Community Journalists Through Library Engagement,” the eight-week program pairs each teen participant with a mentor from The Dallas Morning News and has them come to the library one evening per week for sessions led by the paper’s reporters, editors, and photographers. The teens learn to report, write, and edit their own news stories and take photography workshops with Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists, but they also have the added benefit of learning more about the library and how it can serve them.

Lauren Smart, Storytellers Without Borders program coordinator, notes one advantage of partnering with the library: a multitude of resources—including librarians themselves—that can help the student journalists with their work. For many of the participants, exposure to the library is an important element of the program. “I think, for a lot of the students, this is the first time they’ve walked into a Dallas public library. What the library is and how it functions [is something] that a lot of young people don’t understand in the 21st century,” says Smart, who teaches journalism at Southern Methodist University.

Every session, library staff show participants how to use the archives and other resources at the library to help with their reporting; several students end up using photos they find in the library’s archives to pair with their stories, or look through the library’s back copies of The Dallas Morning News to search for background on whatever local topic they’re reporting on.

While teens from all types of socioeconomic backgrounds have participated in the program, Smart and Melissa Dease, the library’s administrator for youth services, have worked to reach out to students from low-income schools that likely have fewer resources and opportunities to serve teens interested in journalism and writing.

Storytellers Without Borders has also proved beneficial for Dallas Morning News reporters who have gotten involved, says Smart. “The young people have these ideas that the seasoned journalists often have overlooked or aren't particularly aware of. I think it's been a nice initiative for them. They're able to come out of the program with a renewed sense of purpose.”

Banding together to promote news literacy is perhaps one of the most realistic ways for librarians and journalists to collaborate

This includes reporter Dom DiFurio, who saw getting involved as a good opportunity to give back—and as a way to reaffirm some of the reasons he’s a journalist in the first place. “It causes me to rethink the basic principles of journalism,” says DiFurio, who covers breaking business news at the paper and has served as a Storytellers Without Borders mentor as well as teaching classes about interviewing basics. Teens DiFurio has mentored have pursued tough, important stories—from a profile of a teenage Iranian refugee to a student reporting on his own school’s controversial enrollment expansion—that he thinks deserve attention but that the paper doesn’t necessarily have the resources to pursue in-depth. Training the teens how to report on their own communities, DiFurio says, is the perfect way to invest in the future of journalism—especially local journalism. “We need local journalism more now than ever, and if we can expose young generations that are passionate about storytelling to what local journalism looks like and the power and the impact that it can have, all the better.”

One thing the program is intended to do “is not just train journalists but to train civically engaged citizens,” says DiFurio, who, when teaching the class on interviewing, has tried to gauge the news literacy of the participants by asking them where they get their news. “What we’re tackling here is something that the education system has yet to tackle, which is news literacy and critical thinking.”

Putnam adds that banding together to promote news literacy is perhaps one of the most realistic ways for librarians and journalists to collaborate. “There is an essential need for media literacy education, and this need creates lots of room for new ideas and collaborations. School and academic libraries have been teaching increasingly sophisticated forms of information literacy for decades—where they used to teach ‘library skills,’ now they’re teaching life skills that help students navigate a complex and confusing digital landscape,” says Putnam. “There’s an equally important need in the public sphere, and many adults are looking for opportunities to learn more. Librarians and journalists, together, can help fill that need.”

Libraries and librarians will never serve as an adequate replacement for news organizations and journalists. That’s even true in news deserts like Weare, New Hampshire, where Sullivan—the librarian who publishes Weare in the World—is the first to admit this. “I would love it if somebody would move into my little town and start a real newspaper. I'd be more than happy to close up shop on mine,” says Sullivan.