While those of us who make our living at newspapers endured pronouncements of our industry's impending demise, last year someone in Paris was celebrating. The World Association of Newspapers marked the 400th anniversary of the birth of printed newspapers, crediting Johann Carolus with publishing "Relation" in Strasbourg in 1605. And two writers, Shaun O'L. Higgins and Colleen Striegel, went even further, declaring that "the worldwide influence of newspapers is alive and thriving in the postmodern information age."

Shaun O'L. Higgins and Colleen Striegel

New Media Ventures, Inc. 205 Pages. $75.

All of us could use a bit of encouraging news about newspapering. Whether Higgins and Striegel overstate the case for newspapers is debatable given the disheartening scrutiny of Wall Street, but this matters little as we let them guide us through their volume of more than 140 full-color reproductions of artworks reflecting the role of newspapers in art and society. "Press Gallery: The Newspaper in Modern and Postmodern Art" remind us that what many of us do for a living continues to inspire artists to paint, to comment, to build and to assemble, often with scraps of news clippings, metal and dirt on canvas, and occasionally a crowd.

The authors concentrate on roughly the past 120 years, and for the most part they allow the art to tell the story. In an oversized book of 205 pages, they limit the narrative to 44, in which they tell us such things as how early on artists used newspapers mainly as props in their creations. Think of the fashionable paintings of crowds in cafés, where it's easy to spot a newspaper or two. The French Impressionists in the late 19th century shifted the focus to the act of reading. The content of the newspaper appeared to be of scant concern to those masters of light, though their use of newspapers in art never went away entirely. In time, works of art featuring newspapers evolved to become purveyors of political commentary.

A 1960 painting, "Woman With Newspaper" by American artist Richard Diebenkorn, is reminiscent of the early Impressionists' work. The woman sits with a café-au-lait-sized cup of coffee in her right hand, her left hand firmly on the chair's armrest. The newspaper is draped over her lap, and the woman is completely engaged by it. The headlines are big but, for us, illegible. The image celebrates the reader's solitary moments with the paper first thing in the morning, the ritual lift-off considered endangered in our time.

A mixed-media piece, created in 1933, struck me as a fitting monument to life in today's "information age." Man Ray placed a bronze disembodied head in a wooden box and packed it with wadded-up newspapers. "Autoportrait" shows the head "not so much filled with, as buried in, ideas from the press," write Higgins and Striegel. Surf the Web long enough, read all of the publications piled on your desk and the newspapers' print and Web editions, and the feeling Ray's piece evokes will be familiar.

Painted words led to pasted words and, beginning in the early 1900's, Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso — a loyal newspaper reader — started the art of collage, cutting bits of newspapers and pasting them on canvas. Art assumed an edge: Picasso's "Guernica" all but screams war is hell on earth. "The greater a movement's concern with social and political issues," Higgins and Striegel remind us, "the more likely it was to use newspaper clippings, headlines and imagery in its art."

There is in this book a selection of art that displays what Russian artist Alexandr Rodchenko calls "printed matter and revolution." Artists employ the newspaper as a way to comment on Hiroshima, glasnost, the kidnapping of Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades, and the attack on the World Trade Center. A scrap of tribal newspaper from the Spokane Tribe of Indians, along with a clip from the Congressional Record, finds its way into a piece called "Buffalo Bull's Magic Tracks Imprint the Earth," by George Flett.

Pop Art is an essential window through which to explore newspaper's role in art. And as they do, the authors present sweeping statements about how Pop Art established newspapers "as the symbol for mass media in contemporary art." Andy Warhol was its showiest practitioner; his series of "Daily News" paintings elevated the tabloids. "Eddie Fisher Breaks Down" brings those of us from a certain generation right back into the grocery store line, circa 1962.

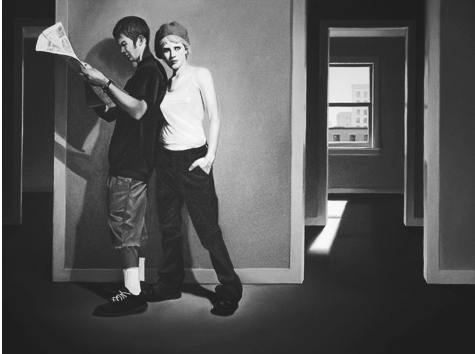

What appeals most about the message of this book is that no rules exist for how artists use newspapers in art. Though there is little shared cultural ground for these artists, newspapers have become a shared tool of storytelling across countries and eras. I see Kenneth Grant's young couple in "Looking For Rooms to Let" in an unnamed city and immediately I am transported to South Congress Avenue in Austin, Texas, the famed haunt of slackers who wouldn't have any luck these days finding a cheap apartment. On a different page, the purses made of laminated recycled newspapers by Maria Capotorto would fit right in on that avenue.

Higgins, a past president of the International Newspaper Marketing Association, and Striegel, who majored in fine arts, have a message to pass along: Newspapers have been a powerful stimulus for artists and still are. That seems small comfort in our times, but I'll take it.

Maria Henson, a 1994 Nieman Fellow, is deputy editorial page editor of The Sacramento Bee.