While 2017 was the year native advertising grew up as a stable revenue source for news, 2018 should be the year the journalism industry establishes clear ethical standards for sponsored content.

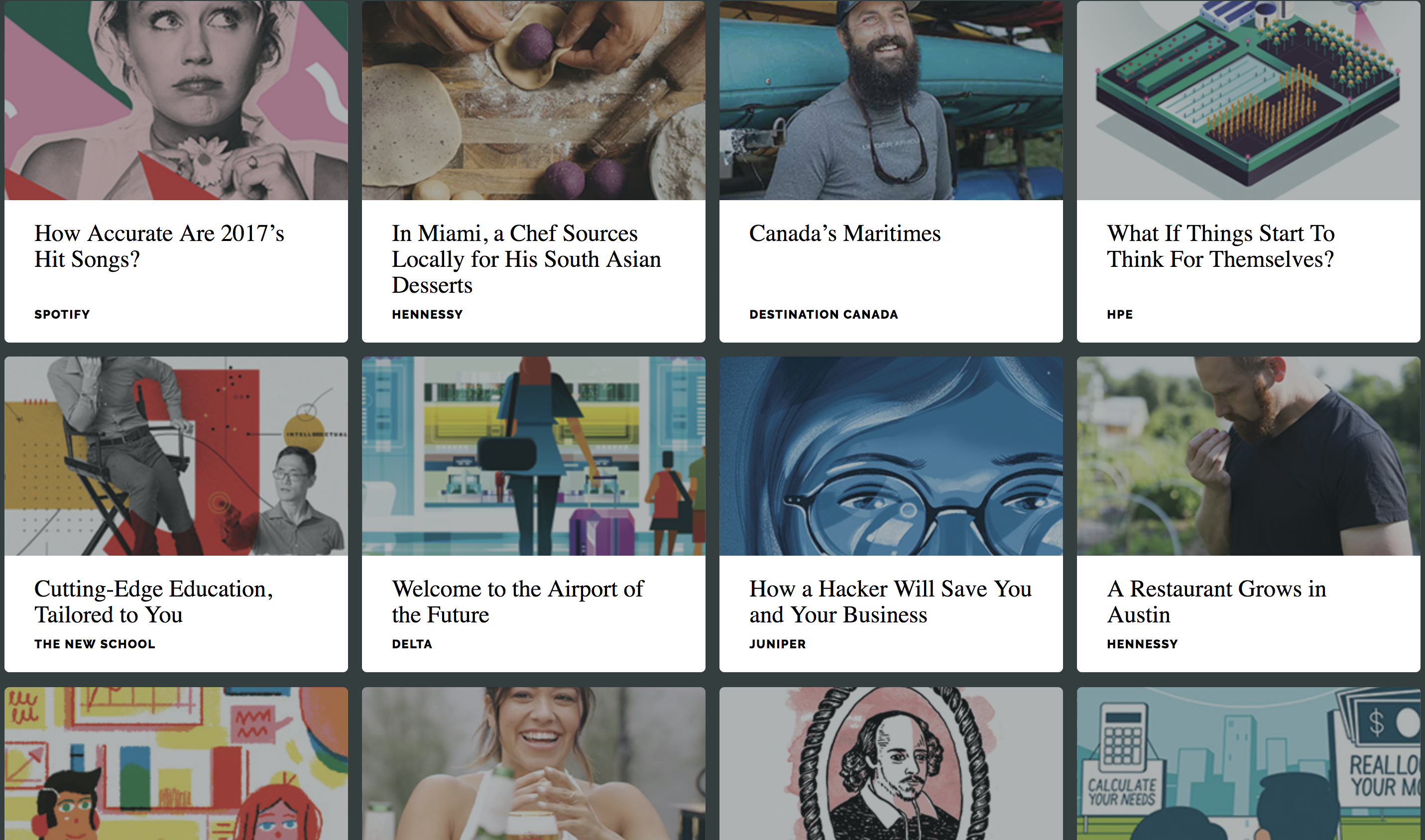

Startups, legacy media, and even nonprofit news outlets are ramping up their native ads, which closely resemble the format of traditional news stories. Unlike intrusive banner ads or pop-ups with a conspicuous sales pitch, native ads seek to position a brand within a broader trend or issue, often via an article, video, or audio delivered with a journalistic storytelling approach. As demand soars for native ads, publishers have created branded content teams or, in some cases, full-fledged studios with more than 100 employees.

During the last half of 2017, I visited media outlets throughout the U.S. and Scandinavia, conducting interviews to learn how the industry is navigating shifting boundaries between editorial and business-side operations. Early adopters of native advertising have learned valuable (and sometimes painful) lessons that spurred them to create or update internal guidelines. Still, nobody could point me to a document that reflects industry-wide consensus on best practices for native ads.

I came away convinced that the news industry should go beyond the current patchwork of government and internal guidelines and collaborate on a code of ethics that spells out how to do native ads right. Here are four suggested steps:

Ethical debates about native advertising frequently focus on how it should be labeled, but any code of ethics also should set forth guidelines for how the content is produced.

Native ads often are written and edited by former journalists who’ve joined the business side as newsrooms cut back on traditional reporting jobs. Some of these ex-journalists tell me they take pride in using their reporting chops to elevate the storytelling of digital advertising while generating revenue that helps pay for watchdog journalism. But if you’re reporting for a native ad instead of a news story, how do you explain yourself to sources?

Gimlet Media, the narrative podcast company that launched in 2014, lacked a clear policy on this during its early days. The confusion led to a public blunder that Gimlet would later address on its flagship podcast, “StartUp.” A new hire As Gimlet described in an episode called “We Made a Mistake,” a frazzled new hire who arranged an interview with a 9-year-old boy forgot to inform the child’s mother that the interview was for an ad, prompting the mom to complain on Twitter that she felt duped.

Gimlet apologized and, in the aftermath, crafted its own set of advertising guidelines. Nazanin Rafsanjani, Gimlet’s creative director, tells me the company has learned from that early mistake. Every interview for an ad or branded podcast now begins with an on-tape declaration that, as Rafsanjani explains it: “We are making an ad, we’re being paid, you’re not.”

WSJ. Custom Studios, The Wall Street Journal’s in-house content agency, requires sources to sign forms making clear that they know they’re being interviewed for an ad. “It’s a lot of signing off on things,” executive editor Sarah Chazan tells me. “We have to make it really clear that there is a separation between church and state.”

While large companies can separate the production of news and sponsored content, smaller operations may not have that luxury. Rebekah Monson, co-founder of WhereBy.Us, a local news startup based in Miami, tells me that while reporters are shielded from native advertising campaigns, production staffers design and edit both editorial and advertising content—and she’s willing to disclose that to readers. “To not use those resources as a small company, we just can’t afford to do it,” she says.

At a time when publishers worldwide are growing more receptive to having editorial teams produce native ads, transparency is an absolute must. “Having as much disclosure as we can is the best way forward,” Monson says.

Axios president Roy Schwartz tells me that while the year-old startup’s journalists and business managers share a common interest in the company’s financial success, everyone understands that editorial independence is key to credibility. Business staffers may communicate with editors about strategic areas of niche coverage, Schwartz says, but “within that content, I’ll never know what’s going to be covered.” If a reporter is working on a scoop unfavorable to an advertiser, he says, “I’m never going to know that, and I shouldn’t know that ... You don’t want a reporter ever second-guessing themselves before writing an article that could be negative to the business side.”

At Quartz, the relationship between business and news staffers is similarly collegial—but not too collegial. “Just because Goldman Sachs is a huge spender in Quartz doesn’t mean that editors are going to pull any punches,” publisher Jay Lauf tells me. On the other hand, Lauf says, sharing best practices “around anything, from headline writing to whether gifs work or whatever, never treads on the integrity line.”

Despite the perception that sponsored content tries to masquerade as news, many of the media outlets I visited said native ads actually perform better the more clearly they’re labeled. Still, the labels can be confusing and inconsistent, ranging from “paid post” (T Brand Studio) to “sponsor generated content” (WSJ. Custom) to “paid placement” (Texas Tribune).

Alongside those labels, publishers also should provide a “What’s This?” link or button that bluntly describes the purpose of the content. At Politiken, one of Denmark’s leading newspapers, commercial editor Line Prasz tells me complaints about native advertising have largely disappeared since the paper unveiled explanatory guidelines for its “premium” native advertising in late 2016.

Unambiguous labeling is in everyone’s best interest, according to Sara Catania, a longtime California reporter and editor who now runs the email newsletter JTrust. Some publishers, Catania says, seem “worried that if they reveal the degree to which advertising influences editorial, they will lose public trust — when, in fact, the opposite is true. If they don’t reveal it, they will be found out, and that’s much worse.”

The FTC released native advertising guidelines in 2015, but many publishers ignore them because enforcement is minimal. SPJ’s Code of Ethics implores news organizations to “distinguish news and advertising and shun hybrids that blur the lines between the two,” but new models have emerged since the code was last revised in 2014. RTDNA’s Code of Ethics advocates for clear labeling of native ads, but doesn’t address how to inform sources during the creation of the content. Other efforts to forge consensus either predate the latest boom in native advertising or are geared toward the advertising industry.

As native advertising becomes more journalistic in approach and news outlets beef up their branded content studios, it’s important for the news industry to prioritize trust by creating, disseminating and following best practices in this emerging area. How’s that for a New Year’s resolution?

Startups, legacy media, and even nonprofit news outlets are ramping up their native ads, which closely resemble the format of traditional news stories. Unlike intrusive banner ads or pop-ups with a conspicuous sales pitch, native ads seek to position a brand within a broader trend or issue, often via an article, video, or audio delivered with a journalistic storytelling approach. As demand soars for native ads, publishers have created branded content teams or, in some cases, full-fledged studios with more than 100 employees.

During the last half of 2017, I visited media outlets throughout the U.S. and Scandinavia, conducting interviews to learn how the industry is navigating shifting boundaries between editorial and business-side operations. Early adopters of native advertising have learned valuable (and sometimes painful) lessons that spurred them to create or update internal guidelines. Still, nobody could point me to a document that reflects industry-wide consensus on best practices for native ads.

I came away convinced that the news industry should go beyond the current patchwork of government and internal guidelines and collaborate on a code of ethics that spells out how to do native ads right. Here are four suggested steps:

1. Clarify the ground rules for a new breed of reporting

Ethical debates about native advertising frequently focus on how it should be labeled, but any code of ethics also should set forth guidelines for how the content is produced.

Native ads often are written and edited by former journalists who’ve joined the business side as newsrooms cut back on traditional reporting jobs. Some of these ex-journalists tell me they take pride in using their reporting chops to elevate the storytelling of digital advertising while generating revenue that helps pay for watchdog journalism. But if you’re reporting for a native ad instead of a news story, how do you explain yourself to sources?

Gimlet Media, the narrative podcast company that launched in 2014, lacked a clear policy on this during its early days. The confusion led to a public blunder that Gimlet would later address on its flagship podcast, “StartUp.” A new hire As Gimlet described in an episode called “We Made a Mistake,” a frazzled new hire who arranged an interview with a 9-year-old boy forgot to inform the child’s mother that the interview was for an ad, prompting the mom to complain on Twitter that she felt duped.

Gimlet apologized and, in the aftermath, crafted its own set of advertising guidelines. Nazanin Rafsanjani, Gimlet’s creative director, tells me the company has learned from that early mistake. Every interview for an ad or branded podcast now begins with an on-tape declaration that, as Rafsanjani explains it: “We are making an ad, we’re being paid, you’re not.”

WSJ. Custom Studios, The Wall Street Journal’s in-house content agency, requires sources to sign forms making clear that they know they’re being interviewed for an ad. “It’s a lot of signing off on things,” executive editor Sarah Chazan tells me. “We have to make it really clear that there is a separation between church and state.”

2. Be transparent about the staffing for native advertising

While large companies can separate the production of news and sponsored content, smaller operations may not have that luxury. Rebekah Monson, co-founder of WhereBy.Us, a local news startup based in Miami, tells me that while reporters are shielded from native advertising campaigns, production staffers design and edit both editorial and advertising content—and she’s willing to disclose that to readers. “To not use those resources as a small company, we just can’t afford to do it,” she says.

At a time when publishers worldwide are growing more receptive to having editorial teams produce native ads, transparency is an absolute must. “Having as much disclosure as we can is the best way forward,” Monson says.

3. Set boundaries for editorial independence

Axios president Roy Schwartz tells me that while the year-old startup’s journalists and business managers share a common interest in the company’s financial success, everyone understands that editorial independence is key to credibility. Business staffers may communicate with editors about strategic areas of niche coverage, Schwartz says, but “within that content, I’ll never know what’s going to be covered.” If a reporter is working on a scoop unfavorable to an advertiser, he says, “I’m never going to know that, and I shouldn’t know that ... You don’t want a reporter ever second-guessing themselves before writing an article that could be negative to the business side.”

At Quartz, the relationship between business and news staffers is similarly collegial—but not too collegial. “Just because Goldman Sachs is a huge spender in Quartz doesn’t mean that editors are going to pull any punches,” publisher Jay Lauf tells me. On the other hand, Lauf says, sharing best practices “around anything, from headline writing to whether gifs work or whatever, never treads on the integrity line.”

4. Clarify the labeling

Despite the perception that sponsored content tries to masquerade as news, many of the media outlets I visited said native ads actually perform better the more clearly they’re labeled. Still, the labels can be confusing and inconsistent, ranging from “paid post” (T Brand Studio) to “sponsor generated content” (WSJ. Custom) to “paid placement” (Texas Tribune).

Alongside those labels, publishers also should provide a “What’s This?” link or button that bluntly describes the purpose of the content. At Politiken, one of Denmark’s leading newspapers, commercial editor Line Prasz tells me complaints about native advertising have largely disappeared since the paper unveiled explanatory guidelines for its “premium” native advertising in late 2016.

Unambiguous labeling is in everyone’s best interest, according to Sara Catania, a longtime California reporter and editor who now runs the email newsletter JTrust. Some publishers, Catania says, seem “worried that if they reveal the degree to which advertising influences editorial, they will lose public trust — when, in fact, the opposite is true. If they don’t reveal it, they will be found out, and that’s much worse.”

The FTC released native advertising guidelines in 2015, but many publishers ignore them because enforcement is minimal. SPJ’s Code of Ethics implores news organizations to “distinguish news and advertising and shun hybrids that blur the lines between the two,” but new models have emerged since the code was last revised in 2014. RTDNA’s Code of Ethics advocates for clear labeling of native ads, but doesn’t address how to inform sources during the creation of the content. Other efforts to forge consensus either predate the latest boom in native advertising or are geared toward the advertising industry.

As native advertising becomes more journalistic in approach and news outlets beef up their branded content studios, it’s important for the news industry to prioritize trust by creating, disseminating and following best practices in this emerging area. How’s that for a New Year’s resolution?