When journalism becomes work—as opposed to adventure—it’s time to move on; that’s what I did after three decades as a reporter and commentator in print and television, at the Oregon Statesman in Salem and KGW-TV in Portland. Later, after 14 years teaching my craft at Western Washington University, I retired and returned part time to the adventure.

It took me into what was, at least for me, a new genre: the quasi-memoir. At first I thought I’d invented the term; Google disabused such thoughts.

Many of us veteran journalists covered a Big Story where we were uniquely connected to the key figures. Such was the case with an iconic period in the political and historical life of Oregon in the middle of the last century. I distilled it in my book “Reporting the Oregon Story: How Activists and Visionaries Transformed a State,” published this year by Oregon State University Press. It describes a creative and bold era (1964-1986) that made Oregon a national leader in environmental policies. The state passed a bottle bill, protected public access to beaches, and established progressive land-use laws, to name a few accomplishments. The era laid the foundations for 21st-century Portland as a national magnet for the young and creative.

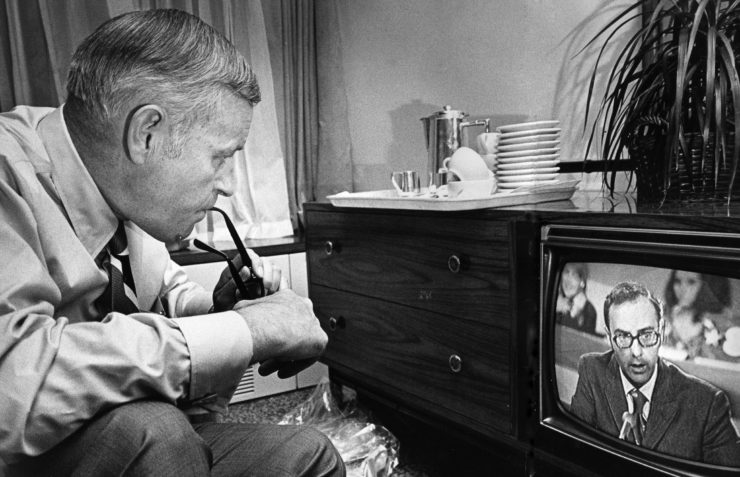

Media and politicians of the era treated each other with skeptical respect and civility; the leading papers and television stations had full-time, experienced political reporters and their stories got good play. It was a prestigious beat. We rubbed shoulders with our sources without constant acrimony and we shared common goals.

In that age of paper, I had filled drawers with scripts, notes, and clips, and carried them with me as I made career moves. Ultimately they fed my writing of “Reporting the Oregon Story,” which was augmented by the personal recollections reporters are wont to exchange over a few drinks.

As a professor, I burnished my interest in regional history, and mixed in with my freelance news stories were academic articles focused on the Pacific Northwest and its media. As I recalled the critical interactions of media and politics during the Oregon Story era, I realized that reporters like me were at the hinge of history, and our reflections would be a contribution to the region’s history and to newcomers young and old who had little knowledge of how their environment was built.

Both the writing and post-publication book events were rewarding; we were “back in the day” and it is still an adventure.

It took me into what was, at least for me, a new genre: the quasi-memoir. At first I thought I’d invented the term; Google disabused such thoughts.

Many of us veteran journalists covered a Big Story where we were uniquely connected to the key figures. Such was the case with an iconic period in the political and historical life of Oregon in the middle of the last century. I distilled it in my book “Reporting the Oregon Story: How Activists and Visionaries Transformed a State,” published this year by Oregon State University Press. It describes a creative and bold era (1964-1986) that made Oregon a national leader in environmental policies. The state passed a bottle bill, protected public access to beaches, and established progressive land-use laws, to name a few accomplishments. The era laid the foundations for 21st-century Portland as a national magnet for the young and creative.

Media and politicians of the era treated each other with skeptical respect and civility; the leading papers and television stations had full-time, experienced political reporters and their stories got good play. It was a prestigious beat. We rubbed shoulders with our sources without constant acrimony and we shared common goals.

In that age of paper, I had filled drawers with scripts, notes, and clips, and carried them with me as I made career moves. Ultimately they fed my writing of “Reporting the Oregon Story,” which was augmented by the personal recollections reporters are wont to exchange over a few drinks.

As a professor, I burnished my interest in regional history, and mixed in with my freelance news stories were academic articles focused on the Pacific Northwest and its media. As I recalled the critical interactions of media and politics during the Oregon Story era, I realized that reporters like me were at the hinge of history, and our reflections would be a contribution to the region’s history and to newcomers young and old who had little knowledge of how their environment was built.

Both the writing and post-publication book events were rewarding; we were “back in the day” and it is still an adventure.