Being a political animal, one of my first thoughts the morning after the election was, “Who’s going to run for President now?”

You can rest assured that there are a dozen or so billionaires slamming their fists on their kitchen tables in frustration that they sat this one out. “I’m smart enough to be president, smarter than him!” But, ultimately, a major part of Trump’s success is his celebrity. He is among the most well-known figures in American culture. The antidote to Trump isn't Elizabeth Warren; it's Oprah.

Dwayne Johnson, the actor better known as The Rock, told British GQ this summer that he could see himself turning to politics: “I can’t deny that the thought of being governor, the thought of being president, is alluring.” I doubt he is the only celebrity considering a mid-career pivot.

In retrospect, we shouldn’t be surprised. News—especially cable news—has been trending steadily toward entertainment over the last decade. There is the explicitly entertainment variety—"The Daily Show"—which still confounds, simultaneously making smart news more accessible and making smart news dumber. And then there is the implicitly entertaining: cable news. CNN and MSNBC have been steadily following the lead of Fox News, year-over-year replacing journalists with pundits at an even pace.

The tension between entertainment and news is an old and familiar one. Bill Paley famously complained at a CBS stockholders’ meeting in 1965 that news coverage—notably of civil rights demonstrations and the funeral of Winston Churchill—had cost stockholders six cents a share due to lost ad revenue. But with the proliferation of channels, from cable to Facebook, the competition for audience has intensified. Celebrity provides a competitive advantage, just at a time when culturally we are downgrading expertise.

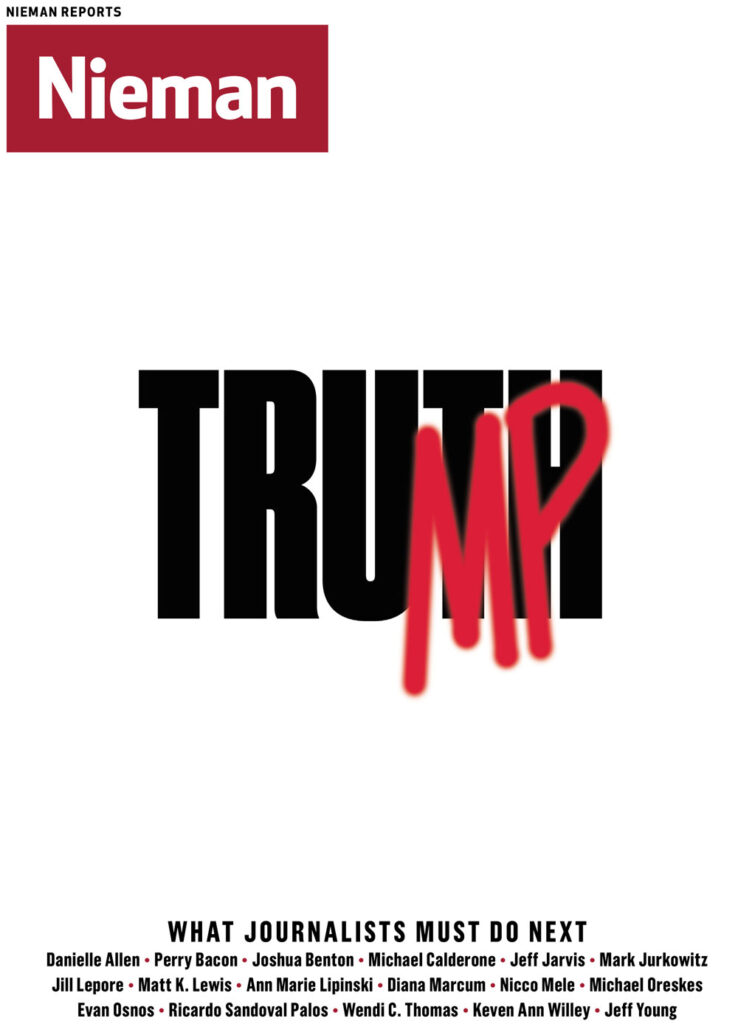

Journalism is familiar with this particular trend. The de-professionalism of journalism has been a small but significant part of emerging tech culture for the last couple of decades. “Content creator” isn’t the same thing as journalist. De-professionalization, when combined with celebrity culture, threatens to overpower journalism, especially with a reality TV star as president of the United States.

With a declining respect for expertise, a worldview inextricably shaped by celebrity, and an intense desire for escapism to avoid the pressing challenges of our moment, Donald Trump seems suddenly inevitable. But a resignation to inevitability is not an honest or just response. There is really only one thing to do: Go local. The emphasis on national politics is drawn like a magnet to celebrity. The stories in our own backyards tether us—an urge we resist with the quiet, hidden calm of Facebook-like intensity—but that local connection is our salvation. It can redeem our journalism and our politics.

De-professionalization, when combined with celebrity culture, threatens to overpower journalism

The local is also not just about the neighborhood. The collapse of local news institutions means that Americans don’t have independent eyes and ears in Washington, D.C. A recent Pew study shows that 21 of 50 states do not have a single local daily newspaper with its own dedicated Congressional correspondent. That means 21 Congressional delegations don’t have to confront a reporter from back home while going about their D.C. business. But that also means 21 states where Americans don’t really know what’s going on in our national government.

The heart of the challenge here is that we do not have a sustainable business model for local news. As Robert Putnam chronicled in his canonical “Bowling Alone,” over the last few decades, Americans went from bowling in organized bowling leagues to bowling by themselves, even as more people started bowling. Putnam showed how over the same time span, Americans purchased more air conditioners, started watching more television, and built fewer homes with front porches. Overall, Americans were staying inside more, not interacting with the neighbors, and becoming more distant from their communities. Local news—and local politics—lose their currency, and celebrity culture asserts itself.

A possible future for journalism is more in the mold of grassroots organizing, where the newsroom becomes a sort of 21st century VFW hall, the hub of local activity. The current buzz is around audience acquisition through social media. What about audience acquisition through local physical presence, opening up potential trickles of revenue from events and other local activities?

The danger of social media “audience acquisition” is that it repeats the mistakes of cable television, rendering us captive to celebrity, national news stories, and clickbait. Newsrooms as “civic reactors,” the beating heart of our communities, offers greater promise—not to mention the skills of grassroots organizing are cousins to traditional news-gathering skills, rather than the alien skills of marketing and public relations.

“Res publica” means, literally, the “real” people. It is up to us to make sure it is not the kind of “real” in reality television, but the kind of “real” you find at PTA meetings and traffic hearings.