“In bringing up my children, I somehow did not get across to them that people have to make compromises,” said Barry Bingham Sr., patriarch of a Kentucky family known for its 20th-century media empire. Jones provided a portrait of the powerful family whose dynasty was crushed by bickering between siblings.

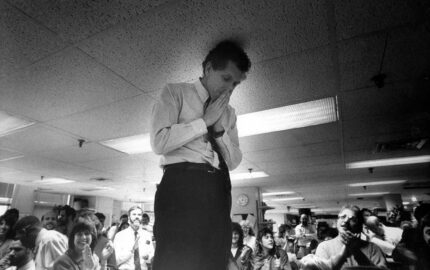

“It’s a sad day for all of us,” said Paul Janensch, executive editor of The Courier-Journal and The Louisville Times, hoarsely addressing several hundred somber co-workers who had jammed the company cafeteria to consider their uncertain future. It was 3 P.M. on Friday, Jan. 10, the day after the abrupt announcement that the Bingham family, the glamorous and tortured clan that had owned the newspapers for almost 70 years, was selling out.

The decision to sell was a shock, but not a surprise. For two years the staff had watched as the Binghams warred with each other over the family holdings. Finally, in desperation, Barry Bingham Sr., the 79-year-old patriarch, decided to sell, hoping that his decision would somehow bring a semblance of peace to the family. What it brought initially was a blistering accusation of betrayal from Barry Bingham Jr., the son who has run the family companies since the early 1970’s.

Barry Jr. resigned in anger and was in the cafeteria to speak. “In my proprietorship here,” he said, “I’ve tried to operate these companies so that none of you would be ashamed of the man you work for.”

When he had finished, the employees rose as one in a standing ovation. Many wept. But the applause was not entirely for Barry Jr., it was also for his stand against selling. And the tears were for themselves, for the uncertain future of the newspapers, for the tragedy of the Binghams and for the passing of an era.

News of the sale prompted a flood of expressions of grief, mostly from Kentuckians, mourning the end of the Bingham stewardship. Under the Binghams, the Courier-Journal won eight Pulitzer Prizes, establishing the newspaper as one of the finest in America.

For large families struggling with the problems of multi-generational ownership of a business, the saga of the Binghams and their failure to hold together was particularly poignant. And for the dwindling number of families still operating their own newspapers, the news from Louisville was chilling.

For the proud Binghams—a clan of southern patricians who are often compared to the Kennedys because they share a history of tragic death and enormous wealth—the pain of selling was redoubled because it may have been avoidable. It is not financial duress forcing the sale, but implacable family strife, as ancient as the struggle between Cain and Abel.