There it is, in the very first sentence of Theodore H. White’s Pulitzer Prize-winning chronicle of the battle between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon for the presidency: The curious challenge of trying to put one’s finger on power. “It was invisible, as always,” White noted, and the “It” alludes to the movement of power—the driving, implacable force that, despite its cataclysmic significance in human destinies, and despite the attempts of journalists to track it to its lair, does not properly exist.

You cannot see power. You cannot hear it or touch it or tuck it in a backpack. You cannot text it. You cannot shake hands with it. You cannot buy it a beer. You cannot send it to its room without supper. Power is pure concept—elusive, intangible, a shadow here, a bit of mist there, a rag of fog and a thread of smoke, a hunch and a wish and a wodge of accumulated intention. Like the wind inside a bellying sail, power can only be spotted by what it does to things that do exist.

White’s book, “The Making of the President 1960,” won the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction. It dealt with a single and seminal political campaign, yes—but at its core, it was about something else, something much larger and even more momentous: Power. Opening his story at the outset of Election Day, painting a picture of citizens lining up at the polls, White continued: “All of this is invisible, for it is the essence of the act that as it happens it is a mystery in which millions of people each fit one fragment of a total secret together, none of them knowing the shape of the whole. What results from the fitting together of these secrets is, of course, the most awesome transfer of power in the world … ”

The effects of power may be overt and obvious—high office, laws, riches, regulations, even life and death—but power itself is only an idea. It is gauzy and mushy and mystifying, and difficult to define with any precision. Journalists have long struggled to find ways to identify and describe power, to keep it from lapsing back into abstraction, and to take on the basic questions: Who has power and who doesn’t—and what do those who possess it manage to do with it once it is in their grip?

A variety of ways abounds to answer those questions, and one of them involves an episode of an animated TV series from the early 1960s featuring a yappy pooch and a seemingly endless supply of evil scientific geniuses—but more about that in a moment.

Power ultimately is the subject of everything journalism does and is, everything journalism ought to be

Some of the best journalism ever produced, including projects that have won the Pulitzer Prize, readily confronts the powerful. Those stories—and genres other than stories, too, such as photographs and novels and editorial cartoons—have, throughout the hundred-year history of journalism’s most coveted honor, constantly held power to account. Their revelations often provoke a public outcry, followed thereafter by legislative and bureaucratic initiatives that attempt to right the now-acknowledged wrong. These stories have changed minds and changed laws. They have resulted in crackdowns and indictments, in lawsuits and house cleanings, in public debates and congressional hearings, in the satisfying takedowns of bullies and bigots, in the ignominious exits of misbehaving presidents and irresponsible CEOs.

The most famous Pulitzer Prizes have, in effect, taken the powerful to the woodshed: The Washington Post’s 1973 win for Public Service recognized the newspaper’s diligent work in linking President Nixon to corrupt behavior gathered under the rubric “Watergate”; the 1972 award to The New York Times in the same category honored its high-stakes publication of the Pentagon Papers, documents that exposed a back-door expansion of the Vietnam War by the Johnson administration.

Power confers the ability to do wrong—to take shortcuts in food production, for instance, that might sicken or kill consumers—but it also confers the ability to do right. After Nathan K. Kotz wrote a series for The Des Moines Register and the Minneapolis Tribune enumerating sanitation shortcuts in meatpacking plants, Congress passed the Wholesome Meat Act of 1967, requiring state inspection of the plants as rigorous as federal standards. Kotz’s investigation won a 1968 Pulitzer for National Reporting. Its real subject was not pork chops, of course, but power—the power wielded by factory owners to compromise safety procedures, and then the power wielded by lawmakers to stop them.

Indeed, you could argue that power ultimately is the subject of everything journalism does and is, everything journalism ought to be. You could make a persuasive case that power is always at the heart of the journalistic mission. Unlike other topics in the history of the Pulitzer Prizes celebrated this centennial year—such as social justice and the long struggle for racial equality—that can be definitively identified in particular stories and then tallied up, power is more diffuse, more ubiquitous. All social justice stories are ultimately about power; not all stories about power are about social justice.

If there is one distinguishing characteristic of Pulitzer-winning work with the explication of power as its raison d’être, it may be this: By and large the stories do not linger long over the pontifical address, the hortatory invective—which is a tempting way to write about something as august and overarching as power. Instead they tend to employ the simplest, most fundamental and yet profoundly effective technique of journalism: intense observation and scrupulous reporting, focusing on the experiences of individuals that illuminate the material impact of power as no slogan or lecture or airy academic study ever could. Ultimately these individual experiences are knitted into a larger, more complex whole, but in order for journalism’s interrogation of power to be meaningful, as Pulitzer-winning work invariably is, the story must start at the root of all stories: the human body.

Bodies themselves—bodies that have suffered inconvenience, injustice, or even torment—are the most devastating testimonies of how power really operates in the world. They are the sails that write the biography of the wind.

In the series of articles by The Boston Globe’s investigative unit about the sexual abuse perpetrated by Catholic priests and the Church’s determination to keep the information under wraps, articles that won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service—and were the basis of the 2015 Academy Award-winning movie—the vivid and disturbing recollections of victims were central to the project’s impact on readers. “In a dark room in the rectory, [Father] Geoghan was sitting in a lone red velvet chair, with two glasses of milk and chocolate chip cookies on a plastic platter,” as a reporter summarized a victim’s account in a story published February 3, 2002. “He hoisted his unsuspecting guest onto his lap, and they said the ‘Our Father.’ That was when Geoghan molested him.”

The imagery was as revelatory as it was hauntingly perverse. A red velvet chair and a platter of cookies: Imperial power yoked to an innocent symbol of childhood. But they weren’t mere symbols to Christopher T. Fulchino, who was 13 years old at the time of his ordeal and 25 when he told his story to a Globe reporter. The anguish induced by these physical manifestations of absolute power and abject vulnerability set up a perimeter fence around his soul. “There is no church he will enter,” the story noted, “because every church reminds him of Geoghan.”

Similarly, in Kathleen Kingsbury’s editorials about the plight of low-wage restaurant workers, which won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing, what stood out were not so much the requisite summaries of the economic theories about the efficacy of a minimum wage, important as that information is, but the scars on the forearms of restaurant dishwashers—wounds that attested to hard work, long hours, and the literal sacrifice of the flesh. The scars were the visible manifestations of power—or in this case, the lack thereof. “The food service industry,” Kingsbury wrote, “is the province of kitchen workers who must enlist government investigators to collect the bare minimum that the law entitles them to receive; wait staff who earn a punishingly low $2.13 per hour nationally in exchange for tips whose distribution is often controlled by management; and fast-food employees who work for chains that explicitly advise them to apply for food stamps and other government aid to supplement their unlivable pay.” The power imbalance between management and labor was clear. Yet the emotional punch of the work—the quality that might rouse a reader to outrage—resided in the stigmata supplied by hot water and mandated haste.

Chris Hamby’s series exploring the mendacious way that coal miners have been systematically cheated out of black lung benefits by a conniving law firm and its well-compensated minions, written for The Center for Public Integrity, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting two years ago. To ram home the reality of the power differential between a gleaming row of glib, experienced lawyers and a humble and ailing miner, Hamby began the series with a simple image: Gary Fox and his wife, sitting in the “stately, wood-paneled chamber” of a federal courtroom in Beckley, West Virginia—their first visit to any courtroom. “Tall, lean and stoic, Fox, then 50, answered the judge’s questions with quiet deference,” Hamby wrote. The coal company’s law firm had engaged in a pattern of aggressive challenges to such claims, the reporter noted, and “as a result, sick and dying miners have been denied the modest benefits and affordable medical care that would allow them to survive and support their families.” The summary pointing out how the powerful have rigged the system was necessary to justify the series—but it was tethered to the body of a dying miner, to his stooped back and stopped-up lungs.

This reliance upon specific details about the body as a means of capturing and holding people’s attention is a more sophisticated version of the advice given by reporter Jack Burden to Willie Stark in “All the King’s Men,” the novel by Robert Penn Warren that won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize—and that excavated the stratified layers of power in street-level politics. Stark, then a fledgling candidate, had just given a speech filled with dry facts. The crowd snoozed. Stark asked Burden for advice: How to move the masses? Here’s the money quote in Burden’s reply: “ ‘Pinch ’em in the soft place.’ ” He meant, of course, that Stark should go for the heart, not the head. That does not mean that people are stupid (although Stark and Burden surely thought so). It means that people are people. They care about other people, especially when those people are being manipulated and mistreated by the powerful.

For decades, tracing the path of power by its discernible effects upon people has been the charge of Pulitzer-winning work

Descriptive passages that marked off Stark’s rise to power were not about power itself—intangible, ungraspable—but about the impact of that power, about what occurred in its wake. As Stark strode past his constituents one sweltering day, his presence was instantly recorded by their reactions: “The people fell back a little to make a passage for him, with their eyes looking right at him,” Burden observed, “and the rest of us in his gang followed behind him, and the crowd closed up behind us.”

For decades, tracing the path of power by its discernible effects upon people has been the charge of Pulitzer-winning work. That work has been accomplished by journalists in large cities or in smaller communities, by investigative reporters and feature writers, by photographers and cartoonists, by editorial writers and playwrights and poets. The 1921 Pulitzer for Public Service was awarded to the Boston Post for its uncovering of the financial fraud perpetrated by Charles Ponzi, the man whose name is now synonymous with pyramid schemes; hapless investors had been bamboozled by promises of quick profits. In 1956, that category was won by the Watsonville [California] Register-Pajaronian for articles that led to the resignation of a district attorney and the conviction of one of his associates. The abuse of power, be it perpetrated by a lone con man or by a gang of elected officials, has been sniffed out by Pulitzer-winning stories since the first awards were handed out a hundred years ago.

Power seems simple at times, a matter of a bully’s fist or a boss’s snarl or a court’s subpoena. But it is a highly complex nexus of the physical and the emotional, of rules and laws, of history and hierarchies.

In 1966, The Boston Globe won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for a series that was instrumental in blocking the ascension of a man of dubious suitability to a federal judgeship. The real topic, however, was power: the hard power of brute political horse trading, and the soft power of friendship, family loyalty, and old associations. These articles were written with fairness and a devotion to factual accuracy, but the final ones swelled to a great emotional crescendo, recounting a scene of Shakespearean grandeur and folly on the floor of the United States Senate, as the two kinds of power—the public and the private, the general and the intimate—crashed and subsided, crashed and subsided, like waves repeatedly striking a high shelf of rock.

The drama began in the fall of 1965 when Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts sponsored the nomination of Boston Municipal Court Judge Francis X. Morrissey to be a federal district judge in that state. As the Globe reported, Morrissey had been deemed “without qualifications from the standpoint of legal training, experience and ability.” Other sources were a bit less fussy, calling him “inept.” Yet as the stories went on to note, Morrissey had the backing of powerful friends: Besides being a pal of Joseph Kennedy, he had worked for Joseph’s son John F. Kennedy during his years in Congress. Thus the nominee’s chief attribute, said a source quoted in a Globe article, was the fact that he “‘never let Joe Kennedy’s coat hit the ground.’”

In deciding whether to vote for Morrissey’s confirmation, senators had to choose either to give fealty to Edward Kennedy or to acknowledge the seemingly inarguable fact of the nominee’s incompetence. In a Globe story published October 16, 1965, reporters James S. Doyle and Martin F. Nolan set up the conflict this way: Senators “were caught between their constituents, their consciences, and the Kennedys.” Different kinds of power were at war with one another. The conflict, with its back-and-forth accusations, with its shuttlecocks of arguments and counterarguments topping the net, grimly continued.

Even within a series featuring a clear-eyed and unsentimental assessment of the crude truncheon of political power, the human element—the body—still was a prominent element. In a story titled “On Senate Floor, The Final Act of an Intensely Personal Drama” published in the Globe October 22, 1965, Nolan quoted Edward Kennedy’s speech to his colleagues. After clearing his throat, in what seemed to be an attempt to clear the emotion from his voice, Kennedy described Morrissey as having grown up “‘poor—one of twelve children, his father a dockworker, the family living in a home without gas, electricity or heat in the bedrooms; their shoes held together with wooden pegs their father made.’” Reporting that portion of Kennedy’s speech turned the scene from a cold exercise in iron-fisted political might—the senator’s colleagues understood the price of opposing him—to one of pudding-soft Dickensian sentimentality. In the end, as the Globe noted, Kennedy, in effect, withdrew the nomination, sparing his colleagues the ordeal of either supporting him—and by extension, supporting an unqualified candidate—or rejecting the nominee and enduring the permanent wrath of one of the nation’s most powerful families.

And just to demonstrate that the Pulitzer Prizes have a healthy sense of irony, the Biography Prize for 1966, the year after the Globe’s stories dramatically demonstrated the Kennedy family’s political clout for ill as well as good, was awarded to Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. for his book “A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House.” Both the dark and light sides of power—the power to push and very nearly succeed in seating an unqualified person on the bench in a federal courtroom, and the power to guide and inspire a nation in a tragically foreshortened period of time by a member of the very same family—were elucidated, each in its turn, by work that carries the Pulitzer imprimatur.

In categories such as Public Service, Investigative Reporting, National Reporting, Local Reporting, and Editorial Writing, the relationship between Pulitzer-winning stories and the topic of power is easy to discern. No one could miss the gross, blundering role of power in Eric Lipton’s series in The New York Times that documented how contemporary lobbyists lavish swag and trips upon attorneys general, congressional representatives, and top staffers at Washington think tanks, a project that won a 2015 prize in Investigative Reporting. “After some time in the hot tub, an evening cocktail reception and a two-and-a-half hour dinner in a private dining room named Out of Bounds,” Lipton wrote at the outset of one of his articles, tagged with a Vail, Colorado, dateline, “Representative Adrian Smith, Republican of Nebraska, made one last stop, visiting the lounge at the Four Seasons Resort hotel here to spend more time with the lobbyists and other donors who had jetted in from Washington, D.C., to join him for the weekend getaway.” The quid pro quo—a soothing froth of hot-tub bubbles in exchange for an elected representative’s integrity—was emblematic of one of the most basic equations in human history: Give me stuff and I’ll do what you want me to.

Power seems simple at times … But it is a highly complex nexus of the physical and the emotional, of rules and laws, of history and hierarchies

Yet across the massive sweep of materials anointed with Pulitzers, there are photographs, editorials, plays, novels, poems, and cartoons that take a subtler and more roundabout approach in tracing the use and misuse of power. Power is more than simply the ineluctable ability of governments and other institutions to compel people to behave in particular ways. Power also manifests itself in family dynamics, relationship issues, and the moral choices that all individuals, at some point in life, must confront. The Pulitzers awarded in journalism categories are able to do this, but so, too, are the winners in the arts categories. The realities of other kinds of power—the influence of peers, the impersonal forces of economic hegemony, the siren song of private demons—have been illustrated by creative works throughout the century, from the stringent social rules that imprisoned elite New Yorkers in Edith Wharton’s “The Age of Innocence,” which won the 1921 prize in the fiction category, to the greedy bankers who swiped the dreams of Depression-era Midwesterners as relentlessly as the dust storms scrubbed the landscape in John Steinbeck’s novel “The Grapes of Wrath,” winner of a 1940 Pulitzer.

The silent, exorable weight of power is urgently present in Max Desfor’s photo from the Korean War, titled “Flight of Refugees Across Wrecked Bridge in Korea.” It was singled out as an outstanding example of Desfor’s coverage of the Korean War for which he received the 1951 Pulitzer in Photography. Across the twisted pillars of the destroyed bridge crawled hundreds of men, women, and children; they resembled ants scrambling on a batch of bent and broken branches. Desperation itself seemed frozen inside the photograph, like something frantic and wild trapped under glass. Beneath the fleeing people was the churning, ice-clogged Taedong River near Pyongyang; above them was a gray, indifferent sky. The presence of power in the photograph is very real—something was forcing them onward, pushing at them with the nasty persistence of a million pitchforks—but it is invisible, that force, for all of its breadth and vigor. The people were escaping the terrors of war. The only way out was to swarm and engulf a doomed bridge.

Edna St. Vincent Millay, who won the 1923 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, was prescient in her vision of what would happen if journalism did not do its job, the job of linking the disparate manifestations of power to make a coherent whole, and to thereby explain how the world operates beneath its deceptively smooth surface. In a portion of her 1939 poem “Upon this age, that never speaks its mind,” she wrote:

Upon this age, that never speaks its mind,

This furtive age, this age endowed with power …

Upon this gifted age, in its dark hour,

Rains from the sky a meteoric shower

Of facts … they lie unquestioned, uncombined.

Wisdom enough to leech us of our ill

Is daily spun; but there exists no loom

To weave it into fabric; undefiled

Proceeds pure Science, and has her say; but still

Upon this world from the collective womb

Is spewed all day the red triumphant child.

The loom that weaves the elements into fabric—the act that turns facts into a story—is another name for journalism.

These days, of course, journalism itself is being upended by a titanic power shift. During the majority of Pulitzer history, the stories have been told by writers and photographers working in familiar places: by and large, venerable journalistic institutions known by the fusty and somewhat condescending label “legacy media.” Increasingly, however, the power to tell the stories about power—and to decide which of those stories should and will be told—has been democratized, spread out amongst a variety of nontraditional venues. No longer do publishing behemoths such as The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal or Time enjoy the exclusive right to decide what constitutes “the news.” As Benjamin Mullin, managing editor of poynter.org, wrote in an essay earlier this year, “Tech companies like Facebook and Google now serve as the primary intermediaries between journalists and their audiences, wresting the power of publication and distribution away from news organizations.”

Mullin’s essay, titled “It’s time to reinvent the Pulitzer Prizes for this media age,” argued that the toppling of the traditional news hierarchy—the ancien regime that kept the Times and its creaky brethren in their bejeweled thrones—should result in new rules for Pulitzers. Some changes have already occurred: News organizations that only publish online have been eligible since 2009. Mullin wants the revolution to be even more disruptive; among his suggestions is the inclusion of work from broadcast outlets, the expansion of the pool of entries to international works, and the addition of readers—regular folks—to the judging ranks, in effect turning the Pulitzers into a sort of People’s Choice Award for journalism.

While journalists were busy doing what journalists have always done—keeping an eye on those who hold inordinate amounts of power, asking penetrating questions and refusing to settle for evasive answers—journalism itself began to undergo a massive change in its power structure, in its funding sources and its business model, in its very future as a profession and as a viable enterprise. And the chaos continues. The Internet-enabled rise of social media, with its ability to slot issues into the national consciousness with the speed of a tweet or an Instagram snapshot or a viral YouTube video, demonstrates this new reality; no longer do the editors at large journalistic organizations get to decide by fiat which issues and problems are worthy of public attention. They have lost a great measure of their power, along with the status that once automatically accrued to their work. This change has occurred so quickly, with such momentous and yet still undetermined implications for the goal of a well-informed citizenry in a representative democracy, that the journalism profession itself is still quivering in shock.

And yet the need is as great as ever for stories that, bravely and audaciously and relentlessly, work what might be called the Power Beat, using the plight of individuals to demonstrate a larger truth about the moral responsibility attendant upon great wealth and power. Such stories are still noble and necessary—but the economic infrastructure to support them is in limbo. It is as if Michelangelo had been forced to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel during an earthquake.

In the midst of this professional tumult and uncertainty, this seething and churning, the archives of the Pulitzer Prizes serve as a beacon, an inspiration, a template, a high-water mark for a profession under existential siege. Pulitzer-winning projects have systematically identified, interrogated, challenged, and explicated power, clarifying just who maintains it and how lives are affected when the powerful prove to be unscrupulous and irresponsible. This sense of purpose was palpable in the work of Taro M. Yamasaki of the Detroit Free Press, winner of the 1981 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography, which documented the dangerous conditions inside Michigan’s state prison in Jackson, or in that of Robert Caro, whose exactingly reported book “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York” won the 1975 Pulitzer Prize for Biography, and which followed the steady accumulation of power by a man whose vision would come to dominate the nation’s largest city.

“Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely”

—Lord Acton

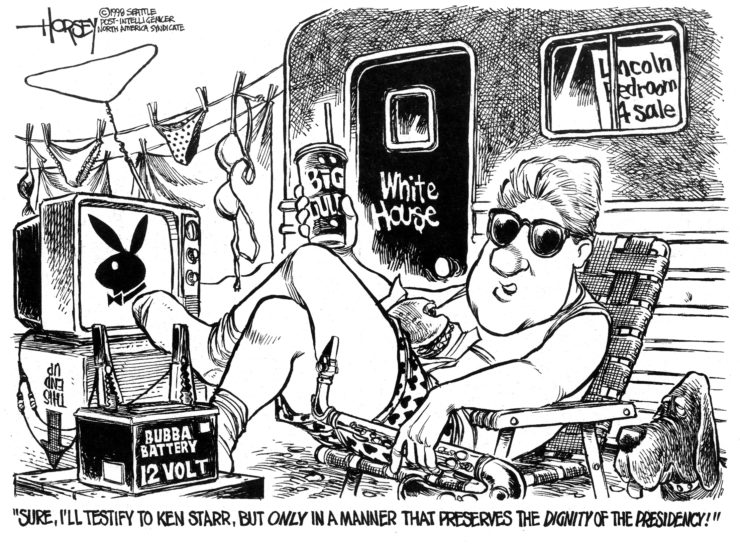

That same year, Garry Trudeau won the Pulitzer for Editorial Cartooning for his “Doonesbury” strip, an upstart and comedic way of tugging on Superman’s cape—of, that is, tweaking the mighty. And David Horsey’s cartoons, which were awarded the Editorial Cartooning Pulitzer in 1999, also fearlessly made fun of the powerful. In one of the winning cartoons, published July 28, 1998, in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Horsey depicted a bloated President Bill Clinton lounging at poolside, looking smug and self-satisfied in shorts and a T-shirt as he ogles the Playboy channel. “Sure, I’ll testify to Ken Starr,” the caricature declares, “but only in a manner that preserves the dignity of the presidency.”

Regardless of the delivery system by which future journalism comes to us—by blog entry or Facebook post or mobile app or some other yet-to-be-dreamed-up means—the question remains: How to pin down a subject as formless and ephemeral as power?

A nifty parable illustrating that challenge is found in an episode of “Jonny Quest,” the animated adventure series created by Doug Wildey that ran from 1964-’65 and in reruns ever since. In an installment titled “The Invisible Monster,” that first aired January 29, 1965, a scientist mistakenly creates a beast comprised of pure energy. The creature was invisible, of course, hence the only way to track it was to follow the path of destruction as it ravaged the landscape, gobbling up all the new sources of energy it could absorb. How to stop such a monster? Ah, leave it to Team Quest: They dumped paint on it. Now it could be seen and captured.

And that, in essence, is what great journalism does: It makes power visible. Usually power prefers to remain behind the scenes, hiding in the shadows, exerting its influence in subtle ways. The exception is when the powerful decide to flaunt their force to cow opponents, relying upon symbols crude or casual—say, pit bulls or pocket squares. Most of the time, though, power likes to conceal itself, manipulating things, further enriching those who already possess it. Much of the work of Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists throughout the last century has been aimed at rousting it out, like a SWAT team raiding a crack house, arriving in a great show of lights and noise and steely purpose. These stories insist that power come out from behind the protective embrace of obliging elected officials and that it justify its dominion over the lives of the powerless. And the stories do this job by teasing out the visible manifestations of power—by picking up clue after clue, and then assembling a portrait of how power really operates. And thus the invisible is made manifest.

“As the transfer of this power takes place,” White writes in “The Making of the President 1960,” “there is nothing to be seen except an occasional line outside a church or school, or a file of people fidgeting in the rain, waiting to enter the booths.” The power-themed works that have won Pulitzer Prizes manage to fasten upon just those ordinary-seeming moments—people “fidgeting in the rain”—to supply glimpses of insight about power as it moves through the world, changing everything, but sometimes doing it in a sly, subterranean way.

Lord Acton, the great Victorian sage whose wisdom was as prodigious as his whiskers, knew a little something about power and its purveyors. In an aphorism that has lost none of its acuity despite being quoted every five minutes or so, he wrote, “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Power is important. It alters those who possess it—how could it not?—just as it alters the world over which they tend to run roughshod. Power is far too crucial to be left unmonitored for long.

The Pulitzer Prizes serve as a beacon, an inspiration, a template, a high-water mark for a profession under existential siege

Pulitzer-winning work has, through the decades, flung bucketfuls of paint on this vast invisible force as it charges forward so that it can be glimpsed, so that its breadth can be measured, its contours clarified. The stark and salient physical details that arise in the wake of power’s march—a red velvet chair, a thick scar on a forearm, the stark X-ray of a dying man’s shriveled and blackened lungs—have been the journalist’s best means of linking the lofty, remote word “power” to the people who wield it, and to the individuals who live according to power’s whims and dictates: the victim of sexual abuse by a trusted authority figure, the dishwasher, the coal miner. These people could be any of us—which means they are all of us. Among the most important responsibilities of journalism is just this joining of the particular to the general, making the connection between an individual’s fate and the fate of society at large. Pulitzer-winning work has often told this story—the story of how power gets what it wants, until newly enlightened readers insist that it be otherwise.

Toward the end of “One of Ours,” the novel by Willa Cather that won the 1923 Pulitzer for Novel, a young man from Nebraska decides to join the fight in World War I. In France, he meets a musician and fellow soldier named David; David’s violin is a brave repudiation of the terrible reverberations of the shelling. And then David stops playing: “‘Listen,’ he put up his hand; far away the regular pulsation of the big guns sounded through the still night. ‘That’s all that matters now. It has killed everything else.’” But Cather’s protagonist did not agree: “‘I don’t believe it … I don’t believe it has killed anything. It has only scattered things.’” The power of the guns was temporary, he insisted. Things would be gathered together again. The world would heal.

Later, the narrator noted, the young man from the Midwest further pondered his point: “Ideals were not archaic things, beautiful and impotent; they were the real sources of power among men.” Well, perhaps. There are many sources of power, of course—some of them positive and inspiring, as Cather’s character had to believe, and some of them terrifying and malign. The task of journalism is to know the difference, and to share that knowledge through the sheer radiant force of stories.