If casting for an act one in this inglorious season of American political journalism, a mid-July moment in The Huffington Post newsroom might do.

“After watching and listening to Donald Trump since he announced his candidacy for president, we have decided we won’t report on Trump’s campaign as part of The Huffington Post’s political coverage,” announced two senior editors. “If you are interested in what The Donald has to say, you’ll find it next to our stories on the Kardashians and The Bachelorette.”

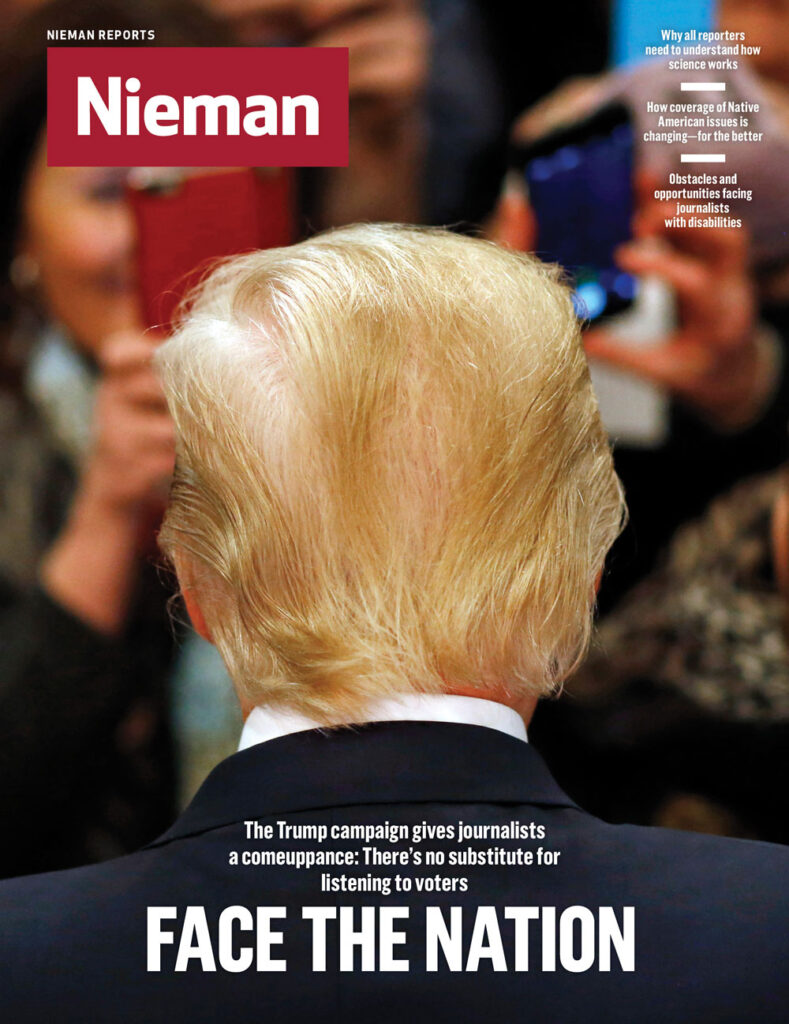

The imperial post was remarkable for its efficient dismissal of what we now know to be millions of voters. Like so many others, these editors didn’t simply fail to foretell the rise of Trump. In deciding for the voters rather than covering them, they missed the story hiding in plain sight, the biggest of this campaign.

That same month, The New Yorker’s Evan Osnos was deep into reporting a piece that would turn out to be one of the most prescient of the season. In “The Fearful and the Frustrated,” he documented a six-state journey through Trump country and his encounters with “a confederacy of the frustrated—less a constituency than a loose alliance of Americans who say they are betrayed by politicians, victimized by a changing world, and enticed by Trump’s insurgency.” All the themes we now know to have fueled Trump’s run were ripe for harvest and arrayed in his August story: economic despondency, toxic views of immigrants, hunger for a “hostile takeover of the Republican Party.”

“Over the last nine months, I was baffled as reporters continued to treat the Trump phenomenon as a joke, even after he and his supporters had provided abundant evidence of their beliefs,” Osnos told me. “Recently, that’s become a story, but it’s very late.”

Instead, proof of Trump’s staying power combined with his escalating bigotry focused the media on the question of how best to characterize a demagogue. Having largely sat out the story that would examine the roots of his dark appeal, many journalists turned to denouncing him and his voters. If you were building a time capsule of Campaign 2016 journalism, you would want to include this media writer’s tweet about an internal newsroom memo: “BuzzFeed Editor-in-Chief: Fair to call Trump ‘mendacious racist.’”

The depth of Trump’s support eluded modern measuring tools

Statistician Nate Silver’s mirror-to-America election forecasts lent a scientific polish to coverage of our last two presidential races. So precise, so accurate, so comforting. I recently reread a talk by a leading national political columnist given at Harvard in the fall of 2007, 12 months before the election and Silver’s laser-sharp predictions. She spoke about the campaign and described the country as “one year away from the coronation of the warrior queen.” Another pundit is later recorded as concurring, asking rhetorically: “Can an African-American man with two years experience in the Senate be more electable than Hillary Clinton?” Big data and Silver’s poll aggregation methods were a welcome assault on the guessing class.

But then came Trump and Bernie Sanders, the surprising socialist who would be president. Silver’s FiveThirtyEight called Sanders’s victory over Clinton in Michigan the “biggest primary polling upset ever.” A post-mortem podcast by Silver and his colleagues reminded me of childhood interrogations by my parents to determine which of their four children was responsible for some household calamity; so much finger-pointing but no clear culprit. At one point in the podcast, an exasperated staffer ventures: “There were a whole bunch of things.”

The limits of modern measuring tools were underscored for me by a riveting recent Guardian story quoting anonymous Trump voters at length, many of them describing themselves as “secret” or “closet” supporters, some fearful of being discovered. “Not even my wife knows,” said one man.

“The data revolution had relied on assumptions about how people behave—evangelicals do X, liberal Acela-riders do Y—and it was enormously effective in a conventional race,” Osnos wrote me. “But when the political weather changed from moderately cloudy to a hurricane, the model failed, and it wasn’t updated to keep pace.”

Osnos recalled leaving his first Trump event in Oskaloosa, Iowa, where he’d interviewed a young mother who approved of the candidate’s views on Mexicans and a “genial” Vietnam veteran who defended Trump’s mockery of John McCain because McCain had “betrayed” him and other Republicans. What he heard that day from “ordinary, otherwise likable people” both alarmed Osnos and confirmed that there was a significant story unfolding.

“These interactions were dispiriting but also revealing,” he said. “Something was happening.”

In her cover story for this issue, The Washington Post’s Juliet Eilperin writes that for journalists to avoid irrelevancy, they must adapt new digital strategies and technologies, just as the campaigns have, but also “return to some of the basics of campaign coverage.” The comment recalled for me a recent Shorenstein Center talk by Harvard historian Jill Lepore detailing both the rise of political polling and data science and the crumbling architecture on which much of it is built. She quoted Edward R. Murrow’s response to Dwight D. Eisenhower’s defeat of Adlai E. Stevenson in 1952: “Yesterday the people surprised the pollsters, the prophets and many politicians. They are mysterious and their motives are not to be measured by mechanical means.”

Vox Pop. Voices. Person on the Street. A tradition of patient voter pulse-taking is still known in many newsrooms by the quaint names that long-dead editors attached to it. It’s a different skill than building “friends” and followers, one that values hearing over collecting.

Say what you will about the mendacious racist. He heard a crack in the earth when none of us was listening.