Even in his first big presidential campaign, in a milieu where few people were short on confidence, Ted Cruz stood out for his self-assurance and conviction that he knew what was best for those who surrounded him.

He was a fresh face on the scene—as we all were—and he was full of promises. Cruz asked for people’s votes within moments of meeting them. And he spread word of his candidacy, complete with the image of his face, in the most modern, efficient way around: a photocopied flier. Tacked to a tree. Or in some cases, to a dorm-room door.

It was 1988. Cruz was 17 years old, a skinny kid from Texas who wanted to be president of the Princeton University Class of 1992. As a fellow class member, and aspiring journalist, I watched the race with passing interest. But it was not to be. Cruz was one of 12 candidates on the initial ballot, but didn’t make it past the primary. Michael Goldberg, an affable, smart kid from Cleveland, eventually won the election. Undaunted, Cruz sought the same position the next year and was again eliminated in the first round of voting. Another conservative Texan—Chad Muir, a popular lacrosse player everyone assumed would eventually run for the nation’s highest office—got more than three times as many votes.

Cruz did eventually make it onto student government, in 1990, and joined the committee on campus safety, the first of many prominent political posts he would hold over the course of his career. And over time his tools of voter outreach became increasingly sophisticated, to the point where in December of last year his current campaign for president mined the data of supporters who posed with Santa Claus in a dozen cities.

Tacking up fliers is ancient history. And, given the technological upheaval of the past four years, to say nothing of the past quarter century, so may be some of the conventions of traditional campaign reporting.

In a year in which there’s been a sprawling presidential race (at least on the Republican side), a fractured media landscape, and unprecedented opportunities for candidates to appeal directly to voters, campaigning and campaign coverage are being transformed. Candidates like Cruz and others are using sophisticated data-mining techniques to identify and target messages to increasingly refined demographic groups. Marco Rubio’s campaign curated and posted short video clips to appeal to specific demographics, and he encouraged voters to consult their second screens during debates. Hillary Clinton used Snapchat’s Live Story feature to send highlights of her first official rally to millions of the platform’s users. Clinton and Bernie Sanders—unfiltered by a television moderator—have conducted an entire line of debate on Twitter about the meaning of “progressive.”

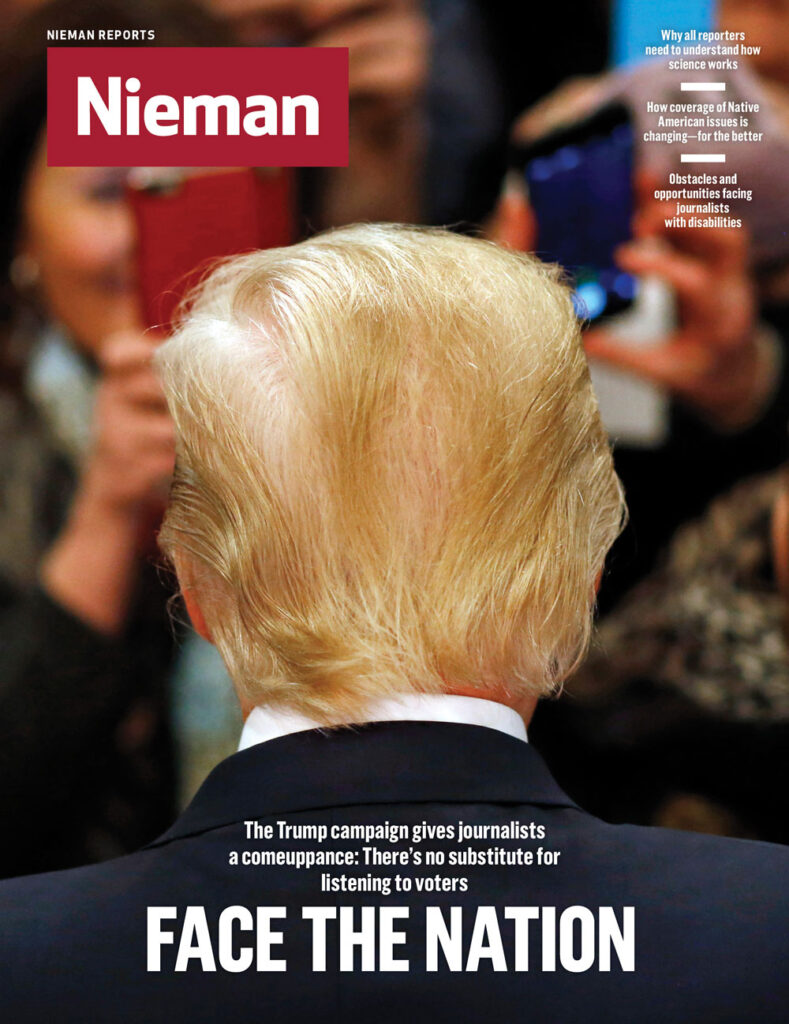

Donald Trump’s triumphant use of social media has allowed him to reach enormous audiences to start and settle feuds, make observations both frivolous and frightening, and drive the news cycle into the ditch of his own choosing. In March, after a protester rushed the stage at a campaign event in Dayton, Ohio, Trump tweeted that the man was affiliated with ISIS. When Chuck Todd on “Meet the Press” told Trump it wasn’t true, Trump said, “All I know is what’s on the Internet.”

Trump more than any other candidate has “managed to fulfill a vision, long predicted but slow to materialize, sketched out a decade ago by a handful of digital campaign strategists: a White House candidacy that forgoes costly, conventional methods of political communication and relies instead on the free, urgent, and visceral platforms of social media,” reporter Michael Barbaro wrote in The New York Times back in October. This new kind of campaign is prompting news organizations, both legacy and digital, to rethink how to cover political candidates.

Social media platforms like Twitter were a factor four years ago, too. But what is different this time around, argues Jill Abramson, a visiting lecturer at Harvard and former executive editor of The New York Times, “is the brutality of minute-by-minute competition and coverage. There’s this wild chase for scooplets. News breaks that no one remembers two days afterwards.” And that frenetic search for news, Abramson argues, has come at a cost.

Though the volume of coverage has grown significantly, no small portion of it has been either hastily assembled, trivial, or, like so much coverage of previous campaigns, focused exclusively on the horse race. The nanosecond news cycle incentivizes reporters to publish as soon as possible and often to elevate snark over substance. Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric guarantees traffic, so his statements garner more attention than crucial policy issues.

A recent study by two Penn State Ph.D. students found that between July and mid-October of 2015 the New York real estate magnate received between 40 and 50 percent of the coverage of all GOP presidential candidates from the three major cable news networks and a selection of local news stations. And that was at a time when so many Republicans were vying for the nomination they couldn’t fit on a single stage. According to the Tyndall Report, which tracks the airtime devoted to various subjects on nightly newscasts, ABC, NBC, and CBS during 2015 dedicated a total of 1,031 minutes to the 2016 presidential campaign. Almost a third, 327 minutes, was devoted to Trump-related story lines, nearly six times more than the next most newsworthy Republican, Jeb Bush (57 minutes), and more than the entire Democratic field combined. Coverage of Clinton’s campaign clocked in at 121 minutes, while Sanders only received 20 minutes.

Hillary Clinton

For years critics of the mainstream media on the left and right have argued that the consolidation of the industry, especially among television networks, and the fact that a handful of wealthy businessmen now control these outlets, has led to myopic coverage that fails to capture the experience of ordinary Americans. For liberals like Sanders, The New York Times’s Jason Horowitz wrote, “the profit-hungry billionaire owners of news media companies serve up lowest-common-denominator coverage, purposefully avoid the income-inequality issues he prioritizes and mute alternative voices as they take over more and more outlets.” Conservatives, meanwhile, say legacy media companies try to bait their candidates into attacking each other but fail to convey the anger many voters feel toward the federal government and officials serving in Washington.

Trump’s name in a headline may lead to additional traffic, but there is a chorus of voices now calling on the media to take a strong stand against him, including Vox’s Ezra Klein, whose video declaring, “He’s so fun to watch that it’s easy to lose sight of how terrifying his rise really is,” garnered hundreds of thousands of shares on Facebook. Harvard University political theorist Danielle Allen went even further, suggesting that “when journalists cover every crude and cruel thing that comes out of Trump’s mouth,” even those reporters purporting to deliver objective coverage are fueling his political ascent. “Perhaps we should just shut the lights out on offensiveness,” she wrote in The Washington Post (Full disclosure: I’m an 18-year veteran of the Post and now serve as its White House bureau chief), “turn off the mic when someone tries to shout down others; re-establish standards for what counts as a worthwhile contribution to the public debate.”

The charged rhetoric around Trump’s campaign erupted into violence in early March, when his supporters clashed with protesters at multiple venues. On March 9, as Rakeem Jones, an African-American protester, was being escorted out of a Trump rally in Fayetteville, North Carolina, John McGraw, a 78-year-old white man, punched him in the face and said Jones might be an Islamist extremist because “he’s not acting like an American.” Trump has suggested he may pay the legal bills of McGraw, who now faces assault charges. The controversy did little to slow Trump’s momentum: in the March 15 primaries he walloped Rubio in Florida, forcing him from the race, and lost just one, Kasich’s home state of Ohio.

During what is incontrovertibly a pivotal election, the press faces a genuine risk of being displaced from its role as a crucial source of insight and information for the electorate. Avoiding this fate will entail a return to some of the basics of campaign coverage, while simultaneously adapting new digital strategies and technologies to remain relevant and accessible. And all of this must be accomplished at a time when most Americans are not enamored with the Fourth Estate. A Pew Research Center survey published in November 2015 found that only the federal government and members of Congress ranked lower than journalists in the public’s esteem. Sixty-five percent of respondents said the national news media had a negative effect on the country, as opposed to 25 percent who described it as positive, while Congress had a ratio of 75 percent negative to 14 percent positive.

Even as more and more journalistic outlets are covering campaigns—Vox with its explainers, BuzzFeed News with its quirky videos and ambitious investigative pieces, The Huffington Post with its long-form documentaries—consumers are increasingly getting their news elsewhere. In some cases, the campaigns themselves are crafting their own content and distributing it to voters through social media. In the 2000 campaign, the Pew Research Center found that reporters, commentators, and other journalists generated 50 percent of the narratives about the candidates, while candidates and their surrogates drove 37 percent. In the 2012 election, those percentages were reversed: Pew estimated that candidates and their allies drove roughly half of the narratives about the campaigns in the press, with the press itself generating roughly a quarter. “In 2012, campaign reporters were acting largely as megaphones, rather than investigators,” says Jesse Holcomb, associate director of research at Pew. “What we found was a striking lack of journalistic intervention in that conversation.”

As politicians and their surrogates dictate more and more of the campaign conversation, John Harwood, who covers politics and the economy for CNBC and The New York Times, notes that even when journalists try to hold candidates responsible for some of their most outrageous claims, they face the challenge that another suite of media outlets—along with the campaigns themselves—can tell targeted audiences why those stories should be ignored. “The influence that was wielded by a small number of news outlets has given way to an inordinate number of competitors,” Harwood says. “Accountability for one is amplification for another … The process is fraught and fractious, and due to the polarization in the country many people are not susceptible to factual argument.”

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of this phenomenon isn’t that it has happened, but the pace and scale of the change. In 2013, while a fellow at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, then-CNN national political reporter Peter Hamby wrote a report titled “Did Twitter Kill the Boys on the Bus?” outlining how social media was degrading the quality of campaign coverage. Invoking “The Boys on the Bus,” the classic account of the coverage of the 1972 campaign by then-Rolling Stone reporter Timothy Crouse, Hamby used Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign as a case study of how social media—particularly Twitter—had produced shallower political journalism. Hamby argued that, as campaigns have become more choreographed, the value of being a reporter on the bus has diminished, and pressure to feed the social media beast has distracted both reporters and audiences from producing and consuming more in-depth coverage. “Put down Twitter and slowly back away,” he advised.

"Due to the polarization in the country many people are not susceptible to factual argument"

—John Harwood, CNBC, The New York Times

Few people—including Hamby himself—have heeded that advice. Hamby now serves as head of news for Snapchat, an app on which the recommended length of a video is less than 10 seconds. Hamby’s conversion from social media skeptic to leading practitioner mirrors the push on the part of news organizations to reach audiences, especially younger audiences, where they are. And where they are is typically not on news sites. Speaking at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center last September, Hamby emphasized that “millions of first-time voters” use Snapchat. “These are people who are not watching television; they’re not reading The New York Times; they’re not reading The Washington Post; they might not even be using Facebook that much,” Hamby said. “But they are living on Snapchat.”

Every day, some 20 million people watch one of Snapchat’s Live Stories, and it has become a coveted audience because, according to the firm, more than 60 percent of smartphone users between 13 and 34 identify themselves as users of the app. BuzzFeed, CNN, Mashable, Vice, Vox, and The Wall Street Journal, among others, are all part of the Discover program, which gives selected publishers a dedicated channel to which they can push curated stories that refresh every 24 hours.

Snapchat is increasingly getting into the content publishing business itself, curating video from users to create Live Stories, which last longer than 10 seconds and also remain accessible on the site for 24 hours. The best ones convey scenes from the campaign trail with a sense of intimacy and immediacy. Using geo-fencing, which identifies users in a specific location at a specific time, Snapchat’s editorial team can capture video from everyone at, say, a Sanders rally, edit together the best moments, add graphics, and then publish it to their 100 million users. “At CNN, we would cover an event with one or two cameras,” Hamby said in his Shorenstein talk. “At Snapchat, we have everyone’s cameras at our disposal.”

The videos provide a pithy, informal look at what’s happening on the trail. One of its more popular stories, on the first GOP presidential debate in Cleveland on August 6, features quick cutaways of Jeb Bush and his wife attending church and Governor John Kasich welcoming everyone to Ohio. At different intervals Hamby gives rapid-fire explainers (why there’s a “JV debate” in addition to the main one, how the candidates are arranged on the stage according to their standing in the polls) and includes kitschy moments like a shot of Cruz’s daughter with a caption dubbing her “debate coach.”

The piece does offer a variety of perspectives—including protesters chanting “GOP, out of touch!” and a brief commentary from Democratic National Committee chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz—but it’s impossible to tell who has shot the different bits of footage, and it doesn’t attempt to provide a rich analysis of what’s happening. And the very fact that Snaps disappear underscores their limited utility, according to Leonard Steinhorn, professor of public communication at American University: “You see it, and it goes away.” When it comes to his own students and their friends, Steinhorn says, “They are informed. But with [Snapchat], and the way they seek out information, it is almost a block, for even the most sincere, to becoming more knowledgeable.”

John Kasich

News outlets are not ceding the social media space but moving aggressively to seize it, crafting content specifically for platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat. A significant portion of Vox’s overall traffic is mobile, so when it creates graphics or other display-oriented pieces, the social media platforms people use on phones guide their efforts. “When we’re making these cool graphics, if they don’t work on the phone, it’s just a wasted effort,” says Sarah Kliff, who oversees the site’s graphics and data team. “It can feel constraining as a newsroom, but it’s really important to meet readers where they are.”

Accomplishing that entails not just engaging in the platforms people are using, but telling stories in ways that hold their attention. Vox helped pioneer the use of “social cards,” which allow reporters to capture a single, telling quote and pair it with an artist’s sketch of the candidate. The cards convey one powerful idea in an instant and can be easily shared.

Vox organizes its coverage differently, too. Reporters cover policy areas rather than individual candidates. Yet Laura McGann, who leads Vox’s politics-and-policy team, acknowledges that the chaotic primary season has led to a juggling of resources to explain some unexpected story lines. “A lot of other outlets are competing to predict who is going to win,” she says. “They look at the micro news events—‘She bought a burrito!’—and ask, ‘Does that mean she will win?” My question is not, ‘What happens next in the campaign?’ The question is, ‘What kind of president would this candidate make?”

Vox’s “gaffesplainer” is a case in point. Back on July 8, Bush made a controversial remark during an interview with the New Hampshire Union Leader’s editorial board, which was live streamed on Periscope, a platform that wasn’t around last election. He said that Americans would have to work longer hours in order to meet his objective of achieving an annual 4 percent growth rate. Democrats pounced on the comment, and the media narrative focused on whether it was a “gaffe.”

Vox’s Matthew Yglesias, by contrast, analyzed the economic theory and statistics necessary to inform an assessment of Bush’s argument. The number of hours people work in a prosperous country tends to decline over time, Yglesias noted, because they become more productive and don’t have to compensate with extra hours. He also noted that the last time the U.S. experienced that level of growth, during the 1990s, Americans were putting in longer hours. Yglesias’s conclusion: Americans already work unusually long hours for those in the developed world and Bush had no specific policy proposals outlining how the U.S. would be able to reach his ambitious goal of sustained, robust economic growth. Vox has done similar work analyzing Rubio’s plan to combat the Islamic State and Clinton’s infrastructure-spending plan.

Vox’s Kliff, in addition to heading the site’s data and graphics team, has spent years covering health care policy. She has published pieces about how Sanders has revived the issue of single-payer coverage with his “Medicare for All” proposal, which led to a spike in readership of the content Vox already had on the issue. Seeing the rise in interest, Vox’s Dylan Matthews reported how the numbers on Sanders's plan panned out.

Matthews explained how the cost was equivalent to spending an additional 8 percent of U.S. GDP on health care, in addition to the 8.1 percent of GDP currently spent, and would give America “about the same level of government spending relative to the economy as you see in the Netherlands, and more spending than you see in the U.K., Germany or Spain.” Sanders’s plan includes a “premium,” which Matthews called what it is: a 2.2 percent flat income tax. Vox’s coverage is noteworthy because it takes candidates’ ideas seriously, scrutinizing where they come from and where they would lead us if they were actually executed.

Bernie Sanders

BuzzFeed News has a team of 17 reporters and editors focused on the campaign, producing everything from quick takes to investigative stories and profiles. In recent years, the Clintons have repeatedly claimed that one of the reasons Bill Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996, which denied federal marriage benefits to same-sex couples even if their marriages were recognized in individual states, was to stave off what they said would have been far worse—a federal constitutional amendment. BuzzFeed’s Chris Geidner dug through thousands of documents the Clinton Library had released on the law and LGBT rights and determined that there was no evidence for the idea that the signing of DOMA was, in the words of Hillary Clinton, “a defensive action.”

And, after a reader tweeted that Trump had voiced opposition to the Iraq War on Howard Stern’s radio show—a position he has trumpeted on the campaign trail—BuzzFeed’s Andrew Kaczynski and Nathan McDermott went through old recordings of the show to determine that he had, in fact, voiced tepid support. “Are you for invading Iraq?” the shock jock asked him. “Yeah, I guess so,” Trump replied.

The Huffington Post has produced several cinematic-quality video series, including “’16 & President” and “New Hampshire,” publishing some directly onto Facebook rather than its own site. In some instances, the raw content resonated with the public. Scott Conroy, senior political reporter for The Huffington Post, says that he and his team had shot footage of an emotional Chris Christie discussing the overdose of a law school classmate who had become addicted to painkillers. The footage didn’t make the final cut of “’16 & President.” “On a slow Friday night, I thought to myself, ‘That was actually a great moment,’” Conroy recalls. He put it online, and it has attracted more than 8.6 million views so far.

More importantly, the series gave viewers a sense of how the New Hampshire primary actually works, and why it is different from other early contests. Everyone talks about how intimate the interactions can be between candidates and voters, but “New Hampshire” captured those moments in real time. And they weren’t just the obvious town hall scenes. A makeup artist who had lost her stepdaughter to a heroin overdose explained how she brought up the issue with every presidential hopeful who sat in her chair; a young digital reporter for CBS, who dropped everything to chronicle the race for nearly a year, got to know John Kasich well enough to tease him about his basketball moves.

The campaigns’ treatment of the traveling press is nearly comical at this point—if it wasn’t so tragic. At one point, Clinton’s handlers put reporters behind a rope line as she walked, making the press corps look like a herd of cattle. She decided to answer a couple of questions from the media right after Super Tuesday, the first time in nearly three months she had done so. Most Republican campaigns aren’t much better. Trump has banned BuzzFeed reporters from his events as credentialed media, though they often attend as members of the public. Trump expelled Jorge Ramos, an anchor for the nation’s leading Spanish-language network, Univision, and the host of a weekly, English-language current affairs program on Fusion, when Ramos tried to ask him about his illegal immigration plan without being called on. He let him back in a few minutes later and allowed him to ask questions.

As a result, even the idea of access itself is coming into question. “The candidates are now so shrink-wrapped and programmed,” says Washington Post national political correspondent Karen Tumulty. “You rarely hear anything spontaneous out of their mouths.”

Adam Nagourney, who served as The New York Times national political correspondent between 2002 and 2010 and covered Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign for USA Today, says that in past elections reporters have been able to see candidates evolve on the campaign trail. “A candidate learns to be a better, smarter, more informed candidate,” says Nagourney, who now serves as the Times’s Los Angeles bureau chief. “Then it really helps to be on the plane. But I don’t know if that’s as valuable anymore. People are much more risk-averse.”

"The question is, ‘What kind of president would this candidate make?’"

—Laura McGann, Vox

Yet traveling with candidates remains essential to in-depth coverage. Nate Cohn of The Upshot, a New York Times section that covers politics and policy, predicted the demise of both Trump and Cruz in 2015. Both he and FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver urged readers to discount Trump’s standing in the polls, suggesting he would inevitably decline. Reporters regularly on the trail thought differently.

For months The Washington Post’s Jenna Johnson traveled with Trump, capturing the massive crowds he attracted as well as their intense anger. Johnson discovered something at the endless rallies that doesn’t show up in a spreadsheet: the devotion of Trump’s supporters. There were some who came to gawk at the spectacle, of course, but they were the exception. “The overwhelming number of people I talk to love him, and adore him, and plan to vote for him,” Johnson says. In October she wrote about the billionaire’s “super fans,” people like Paulette Del Casale, who not only attended four rallies in three separate states in short succession but moderated a private Facebook page dubbed “Trump Defeats the Establishment.”

Reporters and producers of the Reveal podcast, from the Center for Investigative Reporting, found the same when they traveled to Trump events in Nevada, Iowa, and South Carolina. Reporter Katharine Mieszkowski interviewed a down-on-his-luck man, Mike Augustine, who said Trump makes him feel rich inside. His support for the billionaire is so fervent, in fact, that he’s willing to set aside his top political issue—the legalization of marijuana. However, if Trump doesn’t get the GOP nomination, Augustine plans to vote for Sanders.

The “Pumped on Trump” episode of the Reveal podcast is full of surprises about Trump backers. As a follow-up to the January episode, Reveal partnered with online polling company YouGov to paint a picture of the typical Trump supporter. The results: the average Trump backer is white and older than 44; nearly half have a high school education or less, and half make less than $50,000 a year. Twenty-seven percent of respondents said they were independents, while 21 percent said they were Democrats.

Rigorous on-the-ground reporting and newer data-driven techniques can be powerful allies. Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight came to prominence when it correctly called the 2008 election results in every state but Indiana. It later became a licensed feature for The New York Times, before coming to its current home at ESPN in November 2014. When the current site launched, Silver wrote that his ambition was to “make the news a little nerdier” by bringing a data-centric approach to journalism.

FiveThirtyEight has more than two dozen-full time writers and editors and another couple dozen regular contributors. The site’s approach is rooted in a critique of horse-race political journalism in which news blips are presented as key turning points. “FiveThirtyEight got started out of a very specific critique of political journalism, which was that a lot of it was false, basically, that it was overhyped,” says politics editor Micah Cohen. “FiveThirtyEight sometimes gets tagged as anti-traditional journalism, which isn’t really true. It’s just, there are some questions that are answered with this tool—data—and there are other questions that are better answered with other tools—reporting and that kind of thing.”

One question easier answered with data has to do with endorsements—namely, which ones are, or used to be, most valuable to candidates. In presidential primaries, when the party establishment, especially governors and members of Congress, agree on the best person for the nomination, rank-and-file voters have tended to follow suit—something FiveThirtyEight has mapped with its 2016 Endorsement Primary, which assigns weighted point values for endorsements based on the office held by the endorser. As of March 1, Rubio, who has since dropped out of the race, was in the lead with 168 points, much more than Cruz (50) or Trump (29). The endorsement tracker offers a different take on the race than conventional polling, one that highlights the currency political outsiders hold in this race. And while many media outlets consistently treated Rubio like a front-runner because he was favored by many party elites, the primary and caucus results showed that Cruz was Trump’s main rival.

Ted Cruz

Even as many journalists fault social media for making political coverage more superficial, others are using data gleaned from those platforms to enhance and deepen reporting. The Laboratory for Social Machines, an initiative of MIT’s Media Lab, is using Twitter’s entire database of tweets going back to the platform’s launch in 2006 to explore connections among the campaign’s three main players: the candidates, the media, and the public. The MIT team hopes the data can help journalists show how campaign coverage, candidate messaging, and the public’s response converge to shape the election’s most important narratives as well as its outcome.

The project, dubbed The Electome, has the potential to spur “a new kind of journalism about the election, somewhere on the border of what polling used to do and what journalism has always done,” says William Powers, a research scientist at the Lab and former staff writer for The Washington Post, “a view of the election that is more issue-oriented than we’ve gotten in the past and also that includes the public voice having a peer role.”

One of the first things the Electome team set out to learn was how journalists can tap into public opinion to better cover what Powers calls “the horse race of ideas” rather than the horse race among candidates. In December, the Lab teamed up with The Washington Post to publish an analysis of what topics Twitter users were interested in during this election cycle. Using The Electome’s algorithms to comb and sort hundreds of thousands of daily tweets mentioning election issues or candidates, the researchers found that tweets related to foreign policy and national security were the most prevalent, followed by conversations centered on immigration.

Twitter obviously represents only a small subset of the American population, and a not very representative one at that. But if The Electome’s methods can be applied to other social media platforms, the technology could provide an important way to capture the public’s voice and point of view. Powers urges caution when analyzing such data, though, given that these areas of study are still very new. Nevertheless, he says, “Digital technologies have completely revolutionized the public sphere, and journalism hasn’t yet done as much as they might with that. We have a lot to learn about ourselves, about the candidates, and about the issues from this incredibly rich trove of data.”

While it is often difficult to point to discrete turning points in how campaigns are run, two recent landmarks stand out: the January 21, 2010 Citizens United ruling by the Supreme Court, and the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals decision in SpeechNow v. FEC on March 26 of that same year. Citizens United lifted the restrictions on political contributions by corporations and unions as long as they did not contribute directly to candidates or parties, and SpeechNow allowed individuals to pool their money to spend it independently, which spurred the creation of Super PACs.

Those decisions have unleashed a torrent of cash into presidential and congressional campaigns, much of which flows through shadowy third-party groups that are difficult to track. This spike in spending comes at a time when the wealth disparity between rich and poor Americans has grown even wider, bolstering the appeal of Sanders on the left and Trump on the right, since both candidates can make the case that they cannot be easily bought.

"The big hole we have is how [campaign] money is being spent"

—Matea Gold, The Washington Post

In the new world of campaign finance, journalists play a critical role in monitoring who is donating to politicians and how that money is spent. “A lot of reporters are always looking for what’s illegal,” says Carrie Levine, a politics reporter for the Center for Public Integrity. “But, sometimes, the most interesting story is what’s legal. This is classic reporting, and you want to think about the things you think about with any story: Who’s benefiting? Who’s getting rich? Who has the ear of the people in power, and how are they influencing the decisions?”

The New York Times’s Nicholas Confessore and his colleague Sarah Cohen answered some of these questions on February 5 when they scrutinized the spending practices of Trump, who has boasted about the fact that he’s funding his own campaign. Looking at the most recent federal election disclosures, they discovered that of the $12.4 million Trump’s operation spent in 2015—much less than any of his competitors—more than half of it was covered by donations from supporters who have either sent him checks or bought campaign merchandise. Equally important, nearly $2.7 million of the spending went to at least seven firms Trump either owns outright or are owned by people who work for part of his business empire. “What remains is a quintessentially Trumpian endeavor that blurs the line between campaigning and brand building and complicates Mr. Trump’s claims that he is funding his own White House campaign,” they wrote.

Along with Confessore, The Washington Post’s Matea Gold has emerged with one of the clearest voices on the beat. A presidential-campaign veteran, Gold knew little about campaign finance when she took on the beat in the wake of the Citizens United ruling. She quickly realized that the topic “is something so technical and arcane that it’s hard to keep a sense of expertise unless you’re in it all the time.” Yet she thinks it’s vital for voters to know who’s giving money and building influence with the candidates, and says she has noticed, via reader feedback, “the number of people who say they care about big money in politics has grown exponentially.”

Roughly every other week, Gold sends out a briefing to all Post reporters covering candidates. She includes what updated campaign-finance numbers she may have cobbled together as well as intelligence about super PACs worth watching. She might include observations about “how political operatives take advantage of loopholes in law,” she says, or “what outside groups are aligned with which candidates, to make sure all the trail reporters know.”

Working with Tom Hamburger and Jenna Johnson, Gold exposed how officials at a super PAC had ties to Trump even though he had decried the ifdea of these quasi-independent fundraising vehicles. After they wrote about it, the super PAC was shut down. In September, Gold and Hamburger wrote about how both parties have been pursuing wealthy donors, now that limits on contributions have been loosened. “A lot of this can be seen as an esoteric, academic debate,” says Gold. “But if you connect it to a voter in Akron—why you’re seeing your airwaves bombarded by ads from all these groups you’ve never heard of—that’s a really important part of the story.”

Looking forward, Gold hopes technology can bring campaign finance reporting into the 21st century. The FEC website doesn’t post donations in real time, and Senate campaign committees are not even required to submit their financial disclosure reports electronically. “The big hole we have is how money is being spent and seeing quickly who is making money from different entities,” she says. “If I had a wish, it would be for a killer app to see instantly who is profiting.” Some technologists are working to make her wish come true.

At the Center for Responsive Politics, a team of researchers is developing a new data query tool that will give reporters access to real-time campaign finance data. Prompt Data Query (PDQ) is an automated, interactive tool that will allow users to build custom data sets using the Center’s up-to-date campaign finance and lobbying data. Sarah Bryner, the lead on the PDQ project, says this will bring a new level of efficiency and accessibility to making customized data requests in real time.

“Right now, a reporter might e-mail me or someone on my team and ask for all contributions from the fashion industry to members of Congress,” Bryner explains. “We’ll write some queries and deliver that data directly to the reporter.” In a post-PDQ world, though, the reporter would just need to go to PDQ and select her options, setting up a recurring request to get new data whenever she wanted, a process the Center hopes will provide more timely data and, ultimately, get more data into more news stories.

Further Reading

The Future of Political Fact-Checking

by Tatiana Walk-Morris

Loathing on the Campaign Trail

by Ann Marie Lipinski

“Our mission is to increase the visibility of money in politics,” Bryner says, “and we hope that by making it easier for the public to keep a watchful eye on their elected officials, we provide one more roadblock to politicians taking advantage of their power.”

All of these techniques—scrutinizing FEC reports, crunching data from voter files, reporting from the field—share one quality: They take time to produce. It’s so noticeable when talented beat reporters are “given the time to really work on something,” Jill Abramson observes. “It’s amazing, and it’s revelatory. Those are the kind of pieces that I’m hungry for.”

With reporting by Eryn M. Carlson, Jeff Chu, and Sridhar Pappu