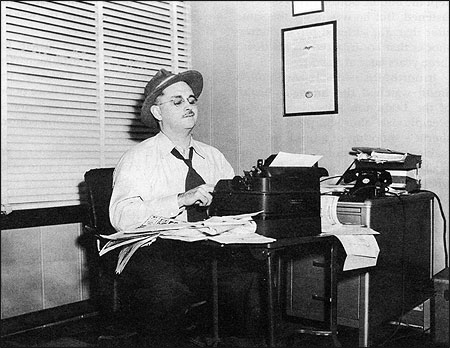

Hodding Carter, Jr., editor and publisher of The Delta Democrat-Times, in the 1940's.

If you grew up a white man in the last great American frontier that was the Deep South in the first half of the 20th century, courage was well understood. It was not a matter of cerebration. It was the instinct that impelled a man to fight rather than to run. For the most part, it was understood to be physical at its core. Those who demonstrated it were respected, if not necessarily loved. Those who flunked the test were held in contempt, or treated as beneath it.

But there was another great cultural leitmotif for the Southern white. Conformity to the code of white supremacy was a supreme value and enforced by all means necessary. Those who deviated,or seemed to deviate, from unblinking commitment to "our way of life," were outside the dominant society's pale. At times, not even silence was enough to prove loyalty. You had to prove it by word and deed. "If you're not with us, you're against us" was an implicit slogan.

Whites treasured what my Dad translated from Sir Walter Scott as the "broadsword virtues." The values of the clan came first. The approbation of the clan was treasured. Isolation from it, expulsion for violating its precepts, was tantamount to spiritual death.

Against that background, and the reemergence of black Southerners as actors rather than victims, running a Mississippi newspaper that questioned racist verities was an invitation to blackballing, economic pressure, physical violence and — potentially rather than ever in fact — death. As the civil rights movement began to crest and the federal government stirred from its 80-plus years of moral slumber, white Mississippi — first my Dad's and then mine — reacted like a baited bear. Its aim was to repel the outsider, punish the white dissenter, and shove the black man back into the ditch.

This was the environment in which Dad founded and ran his small town daily for 21 years, with time off for World War II, and I for the next 15. He had come to Greenville, in Mississippi's Delta, in 1936. The men who backed him, most notably the planter-poet William Alexander Percy, had no reason to believe they were subsidizing a traitor to the white race. His racial views were Southern orthodox.

But his intellectual drive was not, nor were his moral values. He broke the mold early by printing Jesse Owens' picture in the paper — the depiction of the great Olympic runner — breaking the taboo against showing the black man as anything but clown or criminal. When he began to use the honorific "Mrs." in his Delta Democrat-Times to describe black as well as white married women, he broke another. Black women were "girls," or Sally, or nigger.

As a result, even before World War II, he had need for the courage instilled in him by his courageous father, an unblinking segregationist who never backed off from a fight in his tiny Louisiana town. When threatened, Dad threatened back. When warned not to say or do something, he said or did it. Face-to-face was a preferred mode of disagreement. And he filled his home and his office with guns, letting everyone know that he had them close at hand and that killing could be a two-way street.

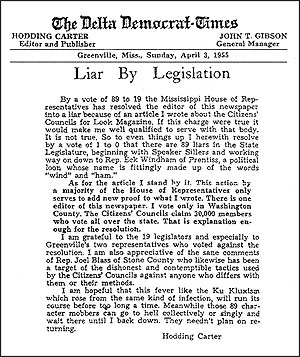

In 1955, Carter responded to the state legislature's censure of him with a front-page editorial.

Speaking for Change

But if Dad broke the Southern code of conformity, he did not do it as a revolutionary. His was an evolutionary journey. He never became what any self-respecting Northern liberal would have called an integrationist. He spoke for the South in scores of articles that alternated their loving depiction of Southern virtues with condemnation of its most blatant and inhuman excesses. He spoke for change, but organic and slow rather than legalistic and fast.

Slow or fast, it was too much for the white majority. A Pulitzer Prize in 1946 for 12 editorials he wrote stressing the need for racial tolerance and respect in the wake of the war against fascism did nothing to swing that majority to his side. Then, in the wake of the 1954 Supreme Court's school desegregation decision he had warned against, he wrote that it had been decided on decidedly American grounds and stepped outside the magic circle for good. With two Look magazine articles condemning the newly founded white Citizens' Council as an "uptown Ku Klux Klan," the war was joined for real. Full-scale economic and circulation boycotts thereafter kept The Delta Democrat-Times isolated within the borders of Greenville's Washington County; he was condemned by the Mississippi legislature.

This is when the need for courage beyond the physical came in. Dad was a Southerner through and through. He wanted to be loved by his fellow white Southerners. The condemnation, the boycotts, the incessant nighttime threatening phone calls were all hard to take. Harder,however, was the sense of isolation from the conforming majority. He spoke ever more vigorously, and he suffered ever more intensely from the hate and scorn of his clansmen. It took a fearsome toll.

They never actually came for him or, later, for me. There was a sense out there that he was a dangerous man, a physical man whom a person would have to kill to silence. No one actually took me for Dad, but I did all I could to encourage comparisons. From the time I returned to Greenville from the Marines until 1964, a pistol was always in my car, in my pocket, in my office desk, and at my bedside. There were places in the Delta I had better sense than to go at night, but I refused to hunker down and withdraw from the larger society, just as he and Mother had lived a full social life in their hometown.

It helps to have a companion in courage if that is what the situation requires, and Mother was that, as well as charming, disarming and conciliatory with all and sundry. She had not been raised for such a life. A French major at Sophie Newcomb College in New Orleans, at 23 she was suddenly thrust into the uncharted waters of crusader's wife when Dad started an anti-Huey Long tabloid daily in his Louisiana hometown in 1933. That was war enough, though never as intense as the one to come. Serene in public, she was often frantically worried in private.

Here is the lesson I learned early from that clash of courage with cultural conformity I witnessed at such close quarters for so long. Real courage consists of looking your fear in the eye, then soldiering on. Dad was afraid much of the time. I was afraid much of the time, too, from my assumption of editorial control in 1962 until the moment when white Mississippi had to accept the reality that lone editors were not the problem and that "second reconstruction" was not going to lead to "second redemption." By then, Dad was dead and I was on my way to Jimmy Carter's Washington, D.C. and a new life.

It's an old lesson, but too often unlearned or forgotten. Mortal men and women set course, encounter adversity, are terrified — and press on. Not gods or superheroes — mere men and women. The enemy can be as determined and vicious and lethal as the white racists of Mississippi a half-century and less ago — or even worse or even less. What is required, what Dad showed me, is that you suck up your gut and do the best you can.

It's an old lesson, but its application by Betty and Hodding Carter in one Mississippi Delta town during the time when "never-ever" gave way now remains the most important of my life.

Hodding Carter III, a 1966 Nieman Fellow, is professor of leadership and public policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.