During the last weeks of editorial cartoonist Bill Mauldin’s life, he was visited by countless World War II veterans; many came dressed in the same fatigues they had worn more than a half-century earlier. Most of these men, in their late 70’s, 80’s and 90’s, carried medals and tattered photographs and newspaper clippings from a day long ago to share with Mauldin, whose body was in constant agony from a scalding in a bathtub accident and whose mind was ravaged by Alzheimer’s disease.

In his riveting biography, “Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front,” Todd DePastino tells the story of how old soldiers came to pay their last respects to Army Sergeant, Technician Third Grade Bill Mauldin, who had distinguished himself not on the battlefield but by capturing the verities of the battlefield in his cartoons that appeared in the military publication Stars and Stripes.

Jay Gruenfeld, then 77 years old, was wounded five times while fighting in the Philippines. As Gruenfeld recovered in an army hospital, he received a copy of Mauldin’s book, “Up Front,” which chronicled the life and times of soldiers Willie and Joe with unmistakable irony, humor and poignancy. Gruenfeld never forgot how the book “spoke for him, expressing his grief, exhaustion and flickering hope,” as DePastino put it.

Fifty-seven years later, Gruenfeld now found himself at Mauldin’s bed, pinning his own Combat Infantryman Badge on Mauldin’s pajama shirt. When Gruenfeld returned home, he wrote newspapers and veterans organization to remind them what Mauldin had meant to American soldiers. When word spread about Mauldin, veterans came to his bedside. Others sent cards and letters, telling Mauldin that his cartoons in Stars and Stripes “saved my soul” and “kept my humanity alive.”

One veteran said that he remembered being in a foxhole full of water, reading a soggy Stars and Stripes, and then seeing a Mauldin cartoon and laughing. In one of Mauldin’s most famous drawings, Willie and Joe are in a muddy swamp. Willie, his arm around Joe, says, in earnest, “Joe, yestiddy, ya saved my life an’ I swore I’d pay ya back. Here’s my last pair o’ dry socks.”

Cartoons’ Enduring Power

DePastino’s vignettes of soldiers coming from all over the country to pay homage to Mauldin remind us of the staying power of editorial cartoons. Cartoons are drawn of the moment, but the best ones take hold of us and never let go. They don’t just outlast other cartoons, they outlast written words. Few articles, if any, captured Lyndon Johnson’s failed presidency as well as the David Levine cartoon of Johnson raising his shirt to reveal a gall bladder scar in the shape of Vietnam.

Herblock captured the right-wing hysteria of the 1950’s by showing a man labeled “Hysteria” climbing a ladder to douse the Statue of Liberty’s flame. Thomas Nast’s drawing of the corrupt “Boss” Tweed with a bag of money for a head appeared nearly 150 years ago. The cartoon will remain timely as long as there are corrupt politicians. During World War I, Robert Minor characterized the military’s exploitation of soldiers by drawing a hulking, headless soldier standing next to a medical examiner, who gushes, “At last the perfect soldier.” These drawings are no less timely today than they were in Minor’s day.

Mauldin responded to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy by drawing a weeping Abraham Lincoln. The grief cartoon has since become a cliché—but, in Mauldin’s hands, it captured the nation’s mourning in a way that was sui generis.

Mauldin’s best work was created from his sense of righteous indignation—such as his civil rights era drawing of two rednecks using their clubs on blacks demonstrating for equal rights. “Let that one go,” one redneck says to the other, “he says he don’t wanna be mah equal.” When newspapers insisted that he tone down his cartoons, Mauldin simply refused and left the profession. He would not compromise his integrity.

Mauldin’s death in 2003 came two years after Herblock’s death. Of the five giants of editorial cartooning in the second half of the 20th century, Mauldin and Herblock are dead, Paul Conrad and Pat Oliphant are in their 70’s and 80’s, respectively. Only Garry Trudeau continues to produce work comparable to his best work. Editorial cartooning—like any profession or civilization for that matter—needs its heroes. Heroes, as Joseph Campbell said, tell us what we’re capable of. Maybe if the profession had more heroes, more cartoonists would aspire to great cartoons and not be satisfied with their first drafts.

This is not to say there aren’t a lot of good cartoonists working today. There are. The best cartoonists continue to create work that rises above caricature and simple tomfoolery to the level of satire. They are no different than the best cartoonists of any day. Editorial cartoonists should reveal our leaders as they are and not as their publicists portray them. Satire often tells the truth laughing. But the best satirists use humor as a means to an end and not as an end itself. Too many cartoonists today are simply in it for the laughs. What’s missing from a lot of cartooning is Mauldin’s sense of righteous indignation.

Cartoonists and the Bush Administration

Editorial cartoonists failed, in particular, in their response to the Bush administration and the war in Iraq. Like much of the news media, too many editorial cartoonists fell in line with the government in the months leading up to the invasion of Iraq. Unlike much of the news media, however, editorial cartoonists should have known better. With notable exceptions such as Trudeau, Oliphant, Conrad, Clay Bennett, Ann Telnaes, Ted Rall, Joel Pett and others, they acted more as government propagandists than satirists. They defended the Bush administration’s claims that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction—contrary to the findings of U.N. weapons inspector Hans Blix and U.S. weapons inspector David Kay. Cartoonists were brutal and unconscionable in their portrayals of Blix and Kay, who turned out to be correct, of course.

Nor have editorial cartoonists been as hard on the Bush administration as the Bush administration has been on cartoonists. Administration officials, for instance, once sent a Secret Service agent to interrogate Los Angeles Times cartoonist Michael Ramirez. Ironically, the administration had missed the point of Ramirez’s drawing, which was intended to defend the President. Ramirez, of all people, should have reacted with anger to the administration’s policy of intimidating critics—or those the administration even viewed as critics. Instead, Ramirez continued—and continues—to defend the administration.

If the Bush administration would go to such lengths to intimidate Ramirez, a friend of the administration, what might it do to its real critics? Then-White House press secretary Ari Fleischer used his bully pulpit to condemn cartoonist Mike Marland, who criticized Bush in a drawing appearing in a few New Hampshire newspapers. If Fleischer had intended to send a message, he succeeded. Marland received death threats and had trouble finding newspapers that would publish his work.

When Washington Post cartoonist Tom Toles criticized then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, the Army Joint Chiefs of Staffs, in an unprecedented act, wrote a scathing letter to the newspaper. The cartoon was innocuous enough; the administration simply wanted to punish Toles, a frequent critic. Cartoonist Ted Rall, who also has received death threats because of his criticism of the Bush administration, defended Toles’s freedom of expression in an interview with conservative Fox News commentator Sean Hannity. When discussing how Americans would react if we heard generals were trying to intimidate a cartoonist who criticized the government, Rall said, “We’d be up in arms and rightly so.”

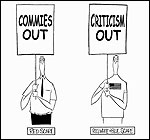

The Bush administration and its friends on Fox News and talk radio have made it a practice to accuse government critics of being unpatriotic. Yet nothing is more patriotic than free speech; criticism of the government is as American as the First Amendment. No profession takes the role of government critic more seriously than editorial cartoonists.

Fox commentator Bill O’Reilly once accused Garry Trudeau of undermining the war effort by having one of Doonesbury’s long-running characters, B.D., lose his leg in battle while on a tour of duty in Iraq. “A case can be made that Trudeau is attempting to sap the morale of Americans,” O’Reilly wrote, calling the strip “irresponsible.” While Trudeau’s cartoon spoke to the reality of what was happening with soldiers and Marines in Iraq, O’Reilly’s condemnation was predictable and misplaced. He, of course, did not mention Trudeau’s monetary contributions to or his involvement with the Fisher House Foundation, which supports a home away from home for families of soldiers recovering from wounds. (Trudeau donated all of the proceeds from his book, “The Long Road,” which detailed B.D.’s own recovery, to this project.)

A lot of soldiers see Trudeau’s comic strip not as undermining the war effort but rather as sensitively addressing the morale of wounded soldiers. “I think it’s fantastic what he’s doing,” said Army Spc. Joe Kashnow, a 4th Infantry Division soldier who lost a leg after being wounded in Iraq in 2003.

Trudeau’s treatment of soldiers is the closest any cartoonist has come to Mauldin’s Willie and Joe since World War II. His defense of soldiers, however, has come with a price. Van Wilkerson, the president of Continental Features, which provided Sunday color comic packages to newspapers in nine southeastern states, strongly supported the administration. He decided to no longer include “Doonesbury” in the package of comics going to 38 newspapers and replaced it with a strip that did not criticize the administration. The editor of one of those newspapers, H. Brandt Ayers at the Anniston (Ala.) Star, called the decision “an obviously political effort to silence a minority point of view” and continued to publish “Doonesbury” inside its paper in black and white.

New Demands of Animation

With job opportunities for cartoonists more and more scarce, many of them feel pressure to obey their editors who, in turn, are pressured by readers who disapprove of their work based on political leanings. When John Sherffius worked for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch he, like Mauldin before him, quit rather than work under the onerous dictates of an editor who insisted that he include criticism of Democrats in cartoons that criticized the Bush administration. The Boulder (Colo.) Daily Camera hired Sherffius, who is currently doing some of the best work in editorial cartooning.

Editorial cartooning, to be sure, has had better days. The fate of editorial cartooning is linked to the fate of the newspaper industry. The industry is in transition. Newspapers, as they have been for centuries, are being replaced by modern technology. Newspaper editors and publishers are holding on with one hand in the past and one in the future. Online newspapers will replace printed newspapers just as talkies replaced the silent movies nearly 80 years ago. The actors who survived were the ones who made the transition.

Likewise, the future of editorial cartooning belongs to those cartoonists who can make the transition from pen or pencil to animation. Thus far, however, something has been lost in the transition. What’s missing from animated editorial cartoons is that sense of purpose—that sense of righteous indignation—that drives great cartooning. Too many editorial cartoonists are concentrating too much on being animators that they’ve forgotten—temporarily, I think—that they’re editorial cartoonists. Too many animated editorial cartoons sing and dance but lack punch. The great Muhammad Ali floated like a butterfly, but he also stung like a bee. Ali’s opponents knew when they’d been hit.

Editorial cartoonists may end up producing work better than anything in past generations. This will require that animation become a means to an end and not the end itself. Editorial cartoonists need to remember their own tradition. Editorial cartoons should grab readers by the shirt collar and shake them out of their indifference. Editorial cartoons should say something. They shouldn’t defend the high and mighty. They should comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Editorial cartoonists need to remember Bill Mauldin and his approach to editorial cartooning. “If it’s big,” Mauldin said, “hit it.”

Chris Lamb is a professor of communication at the College of Charleston in Charleston, South Carolina. He is the author of “Drawn to Extremes: The Use and Abuse of Editorial Cartoons.”

In his riveting biography, “Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front,” Todd DePastino tells the story of how old soldiers came to pay their last respects to Army Sergeant, Technician Third Grade Bill Mauldin, who had distinguished himself not on the battlefield but by capturing the verities of the battlefield in his cartoons that appeared in the military publication Stars and Stripes.

Jay Gruenfeld, then 77 years old, was wounded five times while fighting in the Philippines. As Gruenfeld recovered in an army hospital, he received a copy of Mauldin’s book, “Up Front,” which chronicled the life and times of soldiers Willie and Joe with unmistakable irony, humor and poignancy. Gruenfeld never forgot how the book “spoke for him, expressing his grief, exhaustion and flickering hope,” as DePastino put it.

Fifty-seven years later, Gruenfeld now found himself at Mauldin’s bed, pinning his own Combat Infantryman Badge on Mauldin’s pajama shirt. When Gruenfeld returned home, he wrote newspapers and veterans organization to remind them what Mauldin had meant to American soldiers. When word spread about Mauldin, veterans came to his bedside. Others sent cards and letters, telling Mauldin that his cartoons in Stars and Stripes “saved my soul” and “kept my humanity alive.”

One veteran said that he remembered being in a foxhole full of water, reading a soggy Stars and Stripes, and then seeing a Mauldin cartoon and laughing. In one of Mauldin’s most famous drawings, Willie and Joe are in a muddy swamp. Willie, his arm around Joe, says, in earnest, “Joe, yestiddy, ya saved my life an’ I swore I’d pay ya back. Here’s my last pair o’ dry socks.”

Cartoons’ Enduring Power

DePastino’s vignettes of soldiers coming from all over the country to pay homage to Mauldin remind us of the staying power of editorial cartoons. Cartoons are drawn of the moment, but the best ones take hold of us and never let go. They don’t just outlast other cartoons, they outlast written words. Few articles, if any, captured Lyndon Johnson’s failed presidency as well as the David Levine cartoon of Johnson raising his shirt to reveal a gall bladder scar in the shape of Vietnam.

Herblock captured the right-wing hysteria of the 1950’s by showing a man labeled “Hysteria” climbing a ladder to douse the Statue of Liberty’s flame. Thomas Nast’s drawing of the corrupt “Boss” Tweed with a bag of money for a head appeared nearly 150 years ago. The cartoon will remain timely as long as there are corrupt politicians. During World War I, Robert Minor characterized the military’s exploitation of soldiers by drawing a hulking, headless soldier standing next to a medical examiner, who gushes, “At last the perfect soldier.” These drawings are no less timely today than they were in Minor’s day.

Mauldin responded to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy by drawing a weeping Abraham Lincoln. The grief cartoon has since become a cliché—but, in Mauldin’s hands, it captured the nation’s mourning in a way that was sui generis.

Mauldin’s best work was created from his sense of righteous indignation—such as his civil rights era drawing of two rednecks using their clubs on blacks demonstrating for equal rights. “Let that one go,” one redneck says to the other, “he says he don’t wanna be mah equal.” When newspapers insisted that he tone down his cartoons, Mauldin simply refused and left the profession. He would not compromise his integrity.

Mauldin’s death in 2003 came two years after Herblock’s death. Of the five giants of editorial cartooning in the second half of the 20th century, Mauldin and Herblock are dead, Paul Conrad and Pat Oliphant are in their 70’s and 80’s, respectively. Only Garry Trudeau continues to produce work comparable to his best work. Editorial cartooning—like any profession or civilization for that matter—needs its heroes. Heroes, as Joseph Campbell said, tell us what we’re capable of. Maybe if the profession had more heroes, more cartoonists would aspire to great cartoons and not be satisfied with their first drafts.

This is not to say there aren’t a lot of good cartoonists working today. There are. The best cartoonists continue to create work that rises above caricature and simple tomfoolery to the level of satire. They are no different than the best cartoonists of any day. Editorial cartoonists should reveal our leaders as they are and not as their publicists portray them. Satire often tells the truth laughing. But the best satirists use humor as a means to an end and not as an end itself. Too many cartoonists today are simply in it for the laughs. What’s missing from a lot of cartooning is Mauldin’s sense of righteous indignation.

Cartoonists and the Bush Administration

Editorial cartoonists failed, in particular, in their response to the Bush administration and the war in Iraq. Like much of the news media, too many editorial cartoonists fell in line with the government in the months leading up to the invasion of Iraq. Unlike much of the news media, however, editorial cartoonists should have known better. With notable exceptions such as Trudeau, Oliphant, Conrad, Clay Bennett, Ann Telnaes, Ted Rall, Joel Pett and others, they acted more as government propagandists than satirists. They defended the Bush administration’s claims that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction—contrary to the findings of U.N. weapons inspector Hans Blix and U.S. weapons inspector David Kay. Cartoonists were brutal and unconscionable in their portrayals of Blix and Kay, who turned out to be correct, of course.

Nor have editorial cartoonists been as hard on the Bush administration as the Bush administration has been on cartoonists. Administration officials, for instance, once sent a Secret Service agent to interrogate Los Angeles Times cartoonist Michael Ramirez. Ironically, the administration had missed the point of Ramirez’s drawing, which was intended to defend the President. Ramirez, of all people, should have reacted with anger to the administration’s policy of intimidating critics—or those the administration even viewed as critics. Instead, Ramirez continued—and continues—to defend the administration.

If the Bush administration would go to such lengths to intimidate Ramirez, a friend of the administration, what might it do to its real critics? Then-White House press secretary Ari Fleischer used his bully pulpit to condemn cartoonist Mike Marland, who criticized Bush in a drawing appearing in a few New Hampshire newspapers. If Fleischer had intended to send a message, he succeeded. Marland received death threats and had trouble finding newspapers that would publish his work.

When Washington Post cartoonist Tom Toles criticized then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, the Army Joint Chiefs of Staffs, in an unprecedented act, wrote a scathing letter to the newspaper. The cartoon was innocuous enough; the administration simply wanted to punish Toles, a frequent critic. Cartoonist Ted Rall, who also has received death threats because of his criticism of the Bush administration, defended Toles’s freedom of expression in an interview with conservative Fox News commentator Sean Hannity. When discussing how Americans would react if we heard generals were trying to intimidate a cartoonist who criticized the government, Rall said, “We’d be up in arms and rightly so.”

The Bush administration and its friends on Fox News and talk radio have made it a practice to accuse government critics of being unpatriotic. Yet nothing is more patriotic than free speech; criticism of the government is as American as the First Amendment. No profession takes the role of government critic more seriously than editorial cartoonists.

Fox commentator Bill O’Reilly once accused Garry Trudeau of undermining the war effort by having one of Doonesbury’s long-running characters, B.D., lose his leg in battle while on a tour of duty in Iraq. “A case can be made that Trudeau is attempting to sap the morale of Americans,” O’Reilly wrote, calling the strip “irresponsible.” While Trudeau’s cartoon spoke to the reality of what was happening with soldiers and Marines in Iraq, O’Reilly’s condemnation was predictable and misplaced. He, of course, did not mention Trudeau’s monetary contributions to or his involvement with the Fisher House Foundation, which supports a home away from home for families of soldiers recovering from wounds. (Trudeau donated all of the proceeds from his book, “The Long Road,” which detailed B.D.’s own recovery, to this project.)

A lot of soldiers see Trudeau’s comic strip not as undermining the war effort but rather as sensitively addressing the morale of wounded soldiers. “I think it’s fantastic what he’s doing,” said Army Spc. Joe Kashnow, a 4th Infantry Division soldier who lost a leg after being wounded in Iraq in 2003.

Trudeau’s treatment of soldiers is the closest any cartoonist has come to Mauldin’s Willie and Joe since World War II. His defense of soldiers, however, has come with a price. Van Wilkerson, the president of Continental Features, which provided Sunday color comic packages to newspapers in nine southeastern states, strongly supported the administration. He decided to no longer include “Doonesbury” in the package of comics going to 38 newspapers and replaced it with a strip that did not criticize the administration. The editor of one of those newspapers, H. Brandt Ayers at the Anniston (Ala.) Star, called the decision “an obviously political effort to silence a minority point of view” and continued to publish “Doonesbury” inside its paper in black and white.

New Demands of Animation

With job opportunities for cartoonists more and more scarce, many of them feel pressure to obey their editors who, in turn, are pressured by readers who disapprove of their work based on political leanings. When John Sherffius worked for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch he, like Mauldin before him, quit rather than work under the onerous dictates of an editor who insisted that he include criticism of Democrats in cartoons that criticized the Bush administration. The Boulder (Colo.) Daily Camera hired Sherffius, who is currently doing some of the best work in editorial cartooning.

Editorial cartooning, to be sure, has had better days. The fate of editorial cartooning is linked to the fate of the newspaper industry. The industry is in transition. Newspapers, as they have been for centuries, are being replaced by modern technology. Newspaper editors and publishers are holding on with one hand in the past and one in the future. Online newspapers will replace printed newspapers just as talkies replaced the silent movies nearly 80 years ago. The actors who survived were the ones who made the transition.

Likewise, the future of editorial cartooning belongs to those cartoonists who can make the transition from pen or pencil to animation. Thus far, however, something has been lost in the transition. What’s missing from animated editorial cartoons is that sense of purpose—that sense of righteous indignation—that drives great cartooning. Too many editorial cartoonists are concentrating too much on being animators that they’ve forgotten—temporarily, I think—that they’re editorial cartoonists. Too many animated editorial cartoons sing and dance but lack punch. The great Muhammad Ali floated like a butterfly, but he also stung like a bee. Ali’s opponents knew when they’d been hit.

Editorial cartoonists may end up producing work better than anything in past generations. This will require that animation become a means to an end and not the end itself. Editorial cartoonists need to remember their own tradition. Editorial cartoons should grab readers by the shirt collar and shake them out of their indifference. Editorial cartoons should say something. They shouldn’t defend the high and mighty. They should comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Editorial cartoonists need to remember Bill Mauldin and his approach to editorial cartooning. “If it’s big,” Mauldin said, “hit it.”

Chris Lamb is a professor of communication at the College of Charleston in Charleston, South Carolina. He is the author of “Drawn to Extremes: The Use and Abuse of Editorial Cartoons.”